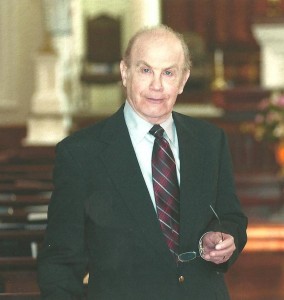

Rabbi Anthony Holz

This interview for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society is being recorded on Wednesday, Oct. 27, 2010, as part of the Columbus Jewish Historical Society’s Oral History Project. The interview is being recorded by phone to Rabbi Anthony Holz. My name is Rose Luttinger and we will begin the interview and then we go into the questions.

This interview for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society is being recorded on Wednesday, Oct. 27, 2010, as part of the Columbus Jewish Historical Society’s Oral History Project. The interview is being recorded by phone to Rabbi Anthony Holz. My name is Rose Luttinger and we will begin the interview and then we go into the questions.

Interviewer: How long were you in Columbus? Where were you born? And where did you live before moving to Columbus? Of course, Beth Tikvah brought you to Columbus.

Rabbi: Yes, I lived in Columbus for two years, from 1981 until 1983. I was born in Cape Town, South Africa. I lived in South Africa until I was 22 in 1964. I then came to the Hebrew Union College and basically lived either after that in Cincinnati, or otherwise for one year in Cape Town and for five years in Pretoria, South Africa. Immediately, the four years before coming to Columbus, we lived in Cincinnati.

Interviewer: You really were all over the world.

Rabbi: Yes, Beth Tikvah was my first, full-time American congregation. In the mid-70s, from 1972 to 1977, my first full-time congregation was in Pretoria, South Africa.

Interviewer: Can you tell us a little bit about your family and your Jewish experience growing up? Who are or were your parents, grandparents? Where were they born?

Rabbi: My parents and all of my grandparents were German refugees. They got out of Germany in the late ‘30s before the Second World War. As a small child, I got to know all three of my grandparents. Both of my grandfathers and my grandmother were alive when I was born. My dad was born in Stuttgart. My mother was born in Oppeln in Upper Silesia. It was a little town at the time, close to Breslau, in a part that Frederick the Great had originally grabbed when they dismantled Poland, and that part is now again part of Poland. As a

small child I knew both of my mother’s parents and I also knew my paternal grandfather. Actually, he had a very big influence on both my life and my brother’s life.

Interviewer: What did your grandfather do for a living?

Rabbi: He was a manufacturer’s representative and so, in fact, was my father.

Interviewer: So you lived in Cape Town growing up?

Rabbi: Yes, I lived in Cape Town until I came to Cincinnati in 1964.

Interviewer: What was the Jewish world like for you in South Africa?

Rabbi: Probably, in many ways, like that of many Americans growing up after the Second World War. I was certainly aware of being Jewish. In fact, my parents growing up had had some disillusioning experiences with the Orthodox Jewish community and they were giving Judaism kind of a last chance, though my mother had had positive experiences in many ways growing up Jewishly, my father had had relatively fewer. But certainly I grew up in a world where there was much less anti-Semitism than there had been in Germany, and significant freedom. When I was six years old, modern Israel had come into existence. I vividly remember the excitement of Israel being born and certainly was aware of what was happening with the different wars that Israel was involved in. Clearly, the Jews in South Africa in 1967 were most excited about the Six-Day War, the Israeli David standing up against the Arab Goliath. All of this was very much part of my consciousness. The South African Jewish community was intensely Zionistic.

Orthodox Judaism at the time was a relatively tolerant variety of Orthodox Judaism. We lived in a part of Cape Town known as the Northern Suburbs and we became friendly with the local Orthodox Rabbi in Bellville, who himself was from Germany. The schools in South Africa would, at the time, have a religious period, usually once a week. At the time, they would let rabbis come and provide the instruction for those who were Jewish. Both Rabbi Zucker and his wife, who was a math teacher, were involved with this high school. And Rabbi Zucker, coming from Germany, was very comfortable, and at various times, in fact, visited us in our house. We never kept kosher and he didn’t make a particular fuss over the fact we weren’t Orthodox. Subsequently, while I previously had some tutors from within the Orthodox community, I took two years of Hebrew at the University of Cape Town. The professor in charge was Rabbi Israel Abrahams, a very famous name in England, but it actually was a different Israel Abrahams, who while he was the Chief Rabbi of the Orthodox in Cape Town, himself was familiar with biblical criticism. He knew that I planned to become a Reform Rabbi. He insisted on being completely objective with all of his students so that I didn’t feel in any way discriminated against or have any particular problems as someone who had Reform Jewish connections and who planned to become a Reform Rabbi.

Interviewer: How did you happen to decide to become a rabbi?

Rabbi: It began as something of a family joke. In actual fact, as part of the background, my mother had a brother who was ordained in the last class of Hochschule fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums, the seminary that ordained Reform Rabbis in Germany. A classmate of his was the first female rabbi, Regina Jonas. Of course she was killed at Theresienstadt. (Note: Jonas was sent to Theresienstadt, where she performed rabbinical function from 1942-1944. She was then moved to Auschwitz, where she was killed.) In, Mishkan T’filah, the latest Reform Jewish prayer book, they have some small quotations from some of her lectures and sermons she gave while at Theresienstadt. That was in the background.

A more direct influence was the fact that my father’s father, Richard Holz, had a very fine voice; he was very musical. I think I’ve inherited musicality from him. I’d go around, about the time that Israel came into existence¸ and I easily picked up all the Hebrew songs, Zionist songs that were around and I would sing them. And he was very proud of me and he would go around telling all his friends: “My grandson Anthony, you watch, one day he’ll become a Rabbi.” It became a joke. Near the end of high school, I became much more intensely interested in going into the rabbinate. With that aim in mind, I took a liberal arts degree at the University of Cape Town. Solomon Freehof, who was a leading American Reform Rabbi and who at one stage was President of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, when he came to Cape Town as part of his visiting different parts of the world, he recommended that I get a general liberal arts degree, a bachelor’s, and essentially I shouldn’t major in Hebrew, but should study courses which would expand my horizons.

Interviewer: You attended college in Cape Town?

Rabbi: I attended the University of Cape Town. I was part of the Student Jewish Association. They would have once-a-month meetings. At various times, we learned how to dance the Hora, there were some programs of Jewish interest. It must have been, in many ways, along the lines of the American Hillel.

Interviewer: You didn’t belong to a Jewish Boy Scout group when you were little, did you?

Rabbi: No, I don’t know there were Jewish Boy Scouts very much at the time.

Interviewer: Well it wasn’t called that. In Switzerland, it was called Brith Hazofim.

Rabbi: Actually where we lived (because when I was eleven we moved away from an area that was adjacent to the downtown Cape Town to a place that was outside Cape

Town, about 20 miles from center, the Northern Suburbs in fact outside the Northern Suburbs), there were very few Jews there. When we moved there, my mother really felt it was very important that we connect with the local Jewish community. The Reform, of course, tended to keep the Jewish holidays, the first day of the holiday, for one day. In South Africa, at the time, if you had a religious holiday you could be out of school, and my brother and I would have liked to have been out of school for more than one day, as fellow Jewish classmates were. And my mother said, “Fine, as long as you attend the Orthodox synagogue on the second days.” So we became quite familiar with a very small Orthodox synagogue in Durbanville, about three miles from where we lived. It was named after one of the early British governors, Sir Benjamin d’Urban.

Interviewer: Where did you meet your wife, and how long have you been married? Where were you married?

Rabbi: We met at the oldest Reform Jewish camp in Oconomovoc, Wisconsin. This was in 1965 at the end of my first year at Hebrew Union College. At the time, her parents lived in Chicago and her father was a Reform Rabbi. We were married in 1966 in Cape Town at Temple Israel.

Interviewer: That’s a common name all over the world it seems like. Rabbi. (Rabbi: Right.) Tell us about your children and their Jewish experiences in Columbus and later.

Rabbi: We have three daughters, the oldest was born in Cincinnati in 1971, Meiera. The younger two, were born when we were in Pretoria, Jessa and Dara. Their Jewish experiences in Columbus were really linked to our experiences because they were all pre-teens. I think that our oldest one, Meiera, probably has had the longest memories. Of course, at the time when we left in 1983, she was not yet 12, but she certainly remembered a great deal of the time at Beth Tikvah. I have no sense of what Jessa’s memories in that connection are. But for Meiera, from then on she became absolutely convinced that as a result primarily of her experience in Columbus, she became convinced that: a) She was never going to become a rabbi and, b) She was never going to marry a rabbi. And she pretty much remained loyal to that notion. She and her husband, they are both Graphic Designers, Jewish. They live in Boston and they have three lovely children. They are our oldest grandchildren.

Jessa never really took a strong automatic position. I never really discussed Beth Tikvah and Columbus with her. She certainly had good friends, which for a while she maintained, but then became much less over time. She has always been very strong in her Jewish identity. At one stage she taught Hebrew when we were first here and for a while helped tutor people in Charleston. She moved to Atlanta and married someone who is not Jewish, but has no particular other religious beliefs. She, In December, graduated from nursing school in Atlanta. They have the currently youngest of our grandchildren. At the moment, we have two grandsons and a granddaughter in Boston, and another granddaughter in Atlanta.

Our youngest, Dara, she was very worried about moving and the Beth Tikvah experience and, I think, for a while very worried about, I think, Jewish life and democracies. She grew up to be a very confident person, eventually. She was the only one who had not finished her high school experience at the time we left Minnesota and she went with us to Charleston and went to the University of Charleston, and eventually moved to Los Angeles, Santa Monica and Los Angeles. A couple of years ago she got her Master’s in Clinical Psychology. She’s now a psychotherapist. She met her husband through J-Date, they got married last Thanksgiving, and she and her 6-foot-4 Israeli husband are expecting twins, boy twins, officially in February but probably earlier. We just came back last night from going there. Today is actually her birthday. We came back because this weekend is the installation weekend for my successor here.

Dara had some short-term, unfortunate feelings about Beth Tikvah. Jessa, at least in any surface way, never retained any long-term memories we talked about. I think she tends to take people and situations largely as they are. I think Meiera’s memories have essentially not changed of the time. They are strongly, clearly Jewishly identified and Meiera has now gotten actively involved in the, I forget the name of the Reform congregation in Newton, where they are members.

Interviewer: Can you tell us about your term as rabbi at Beth Tikvah and some of the issues at the time and what you think would be significant for Beth Tikvah’s history?

Rabbi: Certainly, as you know of course, it was a two-year term; it was my first full-time American congregation. I served previously in American congregations while working either as a rabbinic student or graduate student. I would say that really the main issue at the time for the congregation was the fact that the congregation had recently undergone major change from being really largely an academic congregation centered at OSU. It got this grant of land and funds to build in the Worthington area and became essentially a suburban congregation. Many of the long-time members were actually, I believe, ambivalent about it. Those are two of the changes alone, from being a small, rather intimate, OSU based congregation to being a congregation that was significantly larger. Plus the fact that Rabbi Roger Klein, my predecessor, left because that was not really the kind of congregation he wanted to serve. I think that the congregation hadn’t really taken stock of its internal changes. I think that certainly affected my tenure.

I should say that I contributed to the shortness of my tenure also. If I had come to Columbus straight from my congregational experience in Pretoria, I’m sure I would have come in simply as a rabbi with a congregation, but I spent four additional years doing graduate studies in Cincinnati. And I’m not sure whether this was the message from some of the leadership or it was simply what I wanted to hear but I largely felt that someone who the congregation wanted was academically brilliant and very good at leading discussions. The message that I heard was, whether or not it was the message given, was that the current leadership didn’t know if I was up to Rabbi Klein’s intellectual level. So that I think, Instead of coming in and doing the job of listening, I came in in many ways trying to demonstrate that I was up to the job, which I think was a mistake.

Interviewer: Well, I know you were very interested in Polydoxy at that point and that the congregation had some problems with that.

Rabbi: Right. The trouble was that when the congregation got going they had spent a weekend, the leadership had spent a weekend with Dr. (Alvin) Reines. When I indicated that I had studied with him, I was told by at least one and I think some more of the members of the leadership, “Well, you know that Dr. Reines is really the intellectual founder,” or I think the word was “father of this congregation.” I’m quite sure that this was not the position of all those, but that was the message that I heard. It was the wrong message for me to hear, simply because people are people, Jews are Jews. For me to have come in with (Polydoxy), I think that undoubtedly that was the mistake that I contributed.

Interviewer: Since we’re talking about Polydoxy, can you tell us a little bit about it?

Rabbi: I really try not to use that jargon because basically what Polydoxy is, it’s a variety of Jewish community which operates on the principle of live and let live, that we don’t have a single, infallible truth given at Sinai and that there are legitimately different points of view and that they all have a legitimate place in the Jewish community. In many ways, Mishkan T’filah is operating out of a generally Polydox position, most of the time, in a traditional kind of framework. When you speak about diversity, you mean that there are different points of view about God, about what happens when we die, and that the role of community is to support the individual, and that the individual needs to be part of a larger community which is supportive. These are directly ideas which are part of a Poloydox perspective, at least as far as I would understand it.

Interviewer: What is the Mishkan T’filah?

Rabbi: That’s the new Reform Jewish prayer book. If you look at the prologue, the introductory articles, you can see that they speak about, I don’t have them directly in front of me, I could take a moment just to quote some aspects which are directly related. Some of the people, while not in any way being formally connected to Polydoxy, have been students of him (Reines). His formulation and Eugene Borowitz in New York, both have tended to emphasize the idea that there isn’t a single Jewish way; that there are legitimately a variety of Jewish ways: A point of view that is different from the majority point of view should also be able to be at home in our tradition, in a Jewish Service.

Interviewer: You certainly can’t argue with that, but at the time some people felt it was too way out for them, at least some people in the congregation.

Rabbi: Right. I do think that if we’d started in a different way (Indistinct). My successor was a direct student of Reines and my predecessor had studied with Reines. They knew better than to come in with the jargon.

Interviewer: Did you have any involvements in the Jewish community per se in Columbus?

Rabbi: Yes, I had very positive contacts with my colleagues. I particularly have very warm memories of Harold Berman, the Conservative Rabbi. Since I left, we’ve

had nothing more than a very occasional indirect contact. I’ve known Conservative rabbis who’ve known him. At the time I had certainly positive contact with the larger Jewish community. The old rabbi of Temple Israel, you may remember, he and his wife got divorced and ultimately his son had a Bar Mitzvah at Beth Tikvah that I presided over at the time.

Interviewer: Really, I didn’t remember that.

Rabbi: Right. I certainly had good experiences with the religious school and many of the teachers. I think much of the trouble had to do with the first impressions. I think that the first impressions of when I came there made it impossible for me to be as I really am. First impressions, unfortunately, are very important; many of us operate on that.

Interviewer: When you left us where did you go?

Rabbi: I went to a Duluth congregation, which at the time was a merged congregation, affiliated with both the Reform and the Conservative. I never used the word Polydoxy. Later on I invited Reines as a Scholar in Residence. But I simply went there as a rabbi serving needs. The whole approach I used was that it is not for me to sit in judgement, it is for me to serve the needs of the congregation. As I say, it was both a Reform and Conservative congregation where the Friday evening Services and all evening Services (in the terms of the merger agreement) were all Reform, the morning Services were Conservative. The Friday evening Services had an electric organ and a paid choir. Morning Services tended more toward davening. They had requirements during the merger where the Rabbi would always wear a yarmulke, but the congregation could do as they wished. The synagogue was located in the Jewish Community Center and they would have a kosher kitchen. When I was interviewed they asked me if I would be the mashgiach for the Jewish community kitchen. And my reply was “If the congregation wanted that I would certainly do that.” But I told them, “I have never kept kosher and I do not plan to keep kosher and if you want me to keep kosher, you need to get another rabbi.” They liked that answer so much, that was the answer that got me the job.

Interviewer: So then you had to learn all the intricacies of keeping kashrut?

Rabbi: When I didn’t know the answer, I tried to find the answers, but I never kept kosher. I would call Judy (my wife). When she didn’t know the answer, I would call a Reform colleague who always kept kosher. He was equally influenced by Reines and he and his wife have lived very successful lives in Pittsburgh. So as I say, I don’t have a problem with wearing a yarmulke or not wearing a yarmulke. My personal preference is not to, I grew up in Cape Town wearing it. So I learned how to kasher a kitchen, I learned how to prepare it for Pesach.

Interviewer: And then from there you went to your current. . . .

Rabbi: I was in Duluth, at the time it was both Reform and Conservative. I was there for nine years. From there I came to Charleston which is a very old congregation.

Interviewer: I hear from everyone it’s a lovely congregation and it’s lovely and a nice city to be in.

Rabbi: I personally love it, one of the things I love so much. Of course at the time when I was at Beth Tikvah, there were, perhaps a few families born in the Columbus Jewish community. Most of the members of the congregation had been born elsewhere. The congregation was in many ways really not secure in its identity. When I left Beth Tikvah, I looked for a congregation that was secure in its identity. The Jewish community in Duluth was certainly so, one that had been around for 100 years. A congregation that is secure in its identity doesn’t have a problem with diversity, has much less of a problem accepting change. When I came to Charleston, they asked me and I told them my point of view: how would I deal with the fact that there are so many people in the congregation who are Classical Reformers, love the Union prayer book and others who want to make changes. How would I deal with that? What is my point of view? The congregation is owned by its members, and the rabbi’s role is to help, not to impose his or her religious preferences. On that basis I’ve been here 18 years.

Interviewer: That’s wonderful. I’m sorry that you decided to retire, but I guess that’s good for you.

Rabbi: I do plan to be active, given at the moment, four, hopefully soon, six grandchildren, with probably some others eventually down the line. It is lovely to have more family time. I clearly don’t plan to be a couch potato.

Interviewer: What do you consider to be your most valuable contributions when you were in Columbus?

Rabbi: I think in many ways I really was the interim rabbi which I think congregations have when they try to make a change, certainly when they’ve had a rabbi for a long time or a rabbi whom they have been very close to. I really think I served (reluctantly but inevitably) as the interim rabbi, as a bridge from Roger Klein to Gary Huber. I think that the congregation has always been a congregation which is essentially open to change. I think that it had needed someone to come in because of misgivings about Roger’s leaving. By the time I left, I think the congregation had largely moved on, was ready to change.

Interviewer: Yes, some time had passed since he left. Do you have any other comments that you’d like to make?

Rabbi: That’s of course the message of Question 11. Do you want me to deal with that now? Do I have any message or words of wisdom? A recommendation I would make is that it’s it’s an obligation for the leaders involved to do their homework, that they are aware of who the congregation really is and what its needs are. In addition, I think, if a congregation is having problems with the rabbi, they could bring in the National NCRC, which is made up of rabbis and laypeople to come in to see what the problems are and if there are solutions, other than drastic solutions (Indistinct). I do think that’s something I wasn’t aware of.

Interviewer: I don’t think the congregation was that aware of that either.

Rabbi: To be aware that the Union has a solution for rabbis and congregations. I do think that with Rabbi Huber retiring also now, I believe, I do think that one should try and make sure that for all incoming rabbis the congregation leaders need to understand the congregation and that rabbis are human beings. In retrospect my main role at Beth Tikvah was to be an interim rabbi. When Judy and I retire I may consciously take on that role in the other congregations. When you come in consciously, you know that it’s going to be a one or two-year interim role to step in and help for the short term and that you have no intention of being there longer, and the congregation knows that. I think that’s very helpful.

Interviewer: That should be an interesting way to live for a while.

Rabbi: Sometimes, you know, as Rabbinical students we have bi-weekly pulpits.

Interviewer: One of our, we had an Orthodox congregation who became Conservative because they had problems with the mahetza? They had an interim rabbi who was from Curacao for a couple of years.

Rabbi: The Methodists in the Christian community, they do something like that when someone who has been with them for some length of time retires. The others also do something like it. I do think that rabbis inevitably (Indistinct). We don’t give them a chance. It would be a huge help to new rabbis, to any religion that needs it. I think that the Search Committee when they originally select, they make a good selection. I just think that (interim posts?) are important.

Interviewer: Yes. Well, I thank you very much for your interview. On behalf of the Ohio Jewish Historical Committee, I want to thank you for contributing to the Oral History Project.

* * *

Transcribed by Erin Rabinowitz

Edited by Rose Luttinger

Edited by Rabbi Anthony Holz