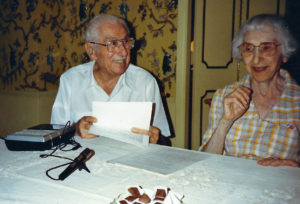

Morris Skilken & Others

(Continued from Tape 1, Side B. Interview was done on July 17, 1989.)

Skilken: And they brought him, he died in Cincinnati, two weeks after he got

the heart attack. His former wife, if I’m not mistaken, is in Heritage House

now.

Interviewer: Yeah?

Skilken: Yeah.

Interviewer: Mrs. Ruben?

Skilken: Yeah. Don’t we have a Ruben there in Heritage House?

Interviewer: Well there’s more than one I think.

Skilken: Yeah. So these camps – we were completely outfitted. We had a tent,

we had gasoline cook stove, 2 burner, and we had, we had built the trunk on the

back end and a box along the one side of this Model T Ford. At that time it had

running boards, you see? And all of our clothes and everything was stored in

there. And we’d pull into one of these camps and we’d pitch our tents and

here are some boxing gloves thrown over a roof, and within a couple of hours, we

were the center of that whole camp – 10, 12, 15 people, tents, some of them were

larger, some were smaller and . . . .

Interviewer: What year was that in?

Skilken: 1919. And so we would work a while, ’til we’d run out of money,

and then we would travel. We would wait, ’til we got some money together to

stay there, bid on a job. And I was a cocky kid. And I’d pull onto a bridge

job where they were laying brick. At that time, they were paying bricklayers

$l.10 to $1.25 an hour, depending on what part of the country you was in. (And I’ll

take one of those too. I didn’t realize I can’t talk and eat but that’s

okay.) And I would say to the foreman on the job, “Don’t need anybody,

kid.” All your tools were in a cement sack. At that time, they used to pack

cement in cloth bags. You would have your tools in a cloth bag and your…

roll. “Don’t need anybody,” I says. “I’ll tell you what.

There’s three of us traveling and I’m on the bum around the country. Just

had enough to eat for breakfast. We don’t have enough money to buy

dinner.” At that time, it was breakfast, dinner and supper. No such a thing

as lunch, you know? If you remember. And I’d say, “You put me on it and

if I don’t lay as many or more bricks than the best man you got on this job in

here, you don’t owe me a damn dime except a couple of bucks to buy something

for supper, for dinner and supper.” Never lost a job.

That’s how I got into the general contracting business. First starting as a little brick

contractor. At that time there was Joe and Harry. They were paying 30 and 35

cents an hour for labor. Whatever job they could get, that’s what they were

making and I was making $l.10 and $1.25 an hour as a bricklayer. So we’d work

for two or three weeks and have enough money, we’d go on. I forget what state

it was in but we were bordering, and this was a big camp. We were bordering the

desert and we were heading for California. And I had a good job and I wanted, we

wanted, and both of the boys had jobs, and we wanted to get enough money put

together so we could get to California and have enough money to get into a

decent camp in California. At that time, they had in L.A., why they had (Fix me

a plate too, will you please, Eleanor?)…

They had enough, they really had

some beautiful tents. They had shower stalls, stuff like that. We had a half a

dozen couples, two of those couples waiting for three weeks, they wanted to go

across the desert with the boys. Well we come off of a mud road and here we find

a beautiful road, five miles wide, it’s the whole desert. Pick any dent in the

road you want, you see? I mean there was five couple waited for us.

Interviewer: Was this in California or New Mexico or where?

Skilken: Probably New Mexico or Arizona or some place.

Interviewer: When did you get married? What year did you get married?

Skilken: 1926. Got married in ’26. January 2nd of 1926. We were 24 years

old.

Interviewer: What was your wife’s maiden name?

Skilken: Maiden name was Fannie Horkin. My father-in-law was a manufacturer in

the stogie business. He manufactured stogies, not cigars. If you remember…

Interviewer: Was that Dr. Horkin in that family?

Skilken: My brother-in-law was the first Jewish dentist in the city of

Columbus.

Interviewer: That’s what he was…

Skilken: Yeah.

Interviewer: You’re right.

Skilken: And had a terrific practice.

Interviewer: You didn’t go for the horses like Joe did, huh?

Skilken: No, no. That’s another story. Well anyway, we ran into Max

Rosenberg. Max Rosenberg, the Rosenberg family lived here in Columbus. Max’s

older sister was married to Lou Lakin. She was a beautiful woman.

Interviewer: Who was the older sister married to? Lou Lakin? The tailor?

Skilken: The tailor, yeah.

Interviewer: He was married to a Cabakoff?

Skilken: No, no.

Voice: He married Mollie Rosenberg.

Interviewer: Well how is the relationships of Bella Wexner?

Voice: He was related to Bella but I can’t tell you how.

Voice: No she was, his wife was related to Bella.

Voice: No Rosenbergs weren’t related to anybody here.

Voice: Then who was the one in the Lakin family that was related to Wexner?

Voice: Maybe it was on the Lakin side.

Voice: Oh no question about it.

General discussion

Voice: Listen, every time I see Bella Wexner, she wants to know what Sandy

and I used to do in school ’cause her was her cousin. Now if that…

Voice: Louis Lakin. It’s my wife’s family. Louis Lakin was part of that

family. My wife…

General discussion

Voice: …Sandy Lakin was the first person in Columbus to lose his life

in World War II.

General discussion

Interviewer: He was married to Ilonka.

General discussion

Voice: Well I’m going back to the other generation. Louie Lakin was married

to Mary and they had two daughters, Harriet was one…

Voice: Uhhhhhhhh, Louie Lakin had one daughter.

Voice: And one son.

General discussion

Voice: Two sons. The first one was Sanford and Norman…

General discussion

Voice: He was President of B’nai B’rith the same time I was President of

the Women’s Chapter and he went overseas…

Voice: And he was the first Jewish boy that was killed. No, no, no. He was

the…

Voice: He was drowned.

Voice: He was drowned. The ship went down just like that.

General discussion

Voice: He was married to Helen Ilonka.

General discussion

Voice: That’s a different Lakin.

General discussion

Voice: No, no, no, no. The Lakin that you knew was a real little short

fellow. He had a shop on State Street.

Voice: That’s right.

Voice: He had a shop on State Street but was not related to these Lakins at

all.

Voice: Sylvia, Sanford Lakin had a sister Bernice who married somebody in

Norfolk, Virginia, and he had a brother Norman who married the Yuster girl.

Remember Yuster, Yuster? They built the building at Fourth and Broad, originally

I mean.

Voice: Well that was who was Norman Lakin’s wife.

Voice: Where is Norman now?

General discussion

Voice: He’s in Florida.

Skilken: He sold his jewelry store to Mansfield, see?

General discussion

Skilken: He and his wife traveled all over the world on one of these passenger

freighters. You know you see a lot of freighters and right in the middle of it,

they’ll take anywhere from 20 to 35 or 36 passengers, you see? And he and his

wife were gone for five months Then he come back to Mansfield and he got sick

and tired of loafing around and he bought out a muffler place, what do you call

them?

Voice: Muffler King?

Skilken: No, no, the other one.

Voice: Midas?

Skilken: Midas Muffler. And it was down, way, way down on the east side in a

lousy place. And I built a place for him at my shopping center up there, West

Park Shopping Center.

Voice: That was later, Morris.

Skilken: Huh?

Voice: That was later, Morris.

Skilken: Yeah. That was later.

Voice: That was after World War II.

Skilken: And then he decided, by this time he was getting up there, where he

decided definitely he’s going to retire now.

Mixed conversation

Voice: See now everything’s quieted down, I’ll tell you about Simon…

He went to Bexley High School and they lived on Oakwood Avenue. ‘Cause his

father paid tuition so he would be with me, Morrey Mattlin and the rest of us.

We all went…together…Sanford Lakin…His father paid

tuition so he could go to Bexley High School. And he preceded me as President of

B’nai B’rith by a term or two. Is that right Sylvia? And his ship was

torpedoed and that’s how he lost his life. And if you remember…

Skilken: Went down in two minute’s time.

Voice: We established a memorial in his memory. The Sandord Lakin award and

it became at that time a very prestigous award…

Mixed conversation

Voice: And he married Ilonka. And I’ll tell you something that’s very

humorous. Every time, you know she was famous for her cooking. Very famous.

Voice: Ilonka’s.

Voice: And then he lived with her on Oakwood Avenue in his father’s house.

Skilken: Took care of Louis for years.

Voice: That’s right. And let me tell you…

Mixed voices

Voice: every time they called up and invited us over for dinner, my wife and

I dropped everything we were doing to go over there and have dinner at the house

because of her cooking. We ate there a lot.

Tarshish:: Well Allen, if you remember, he was active in B’nai B’rith at

that time and so was Sammy. He invited the whole group over to his house.

Voice: He used to do that.

Tarshish:: And Allen came home and he was raving about the food.

Skilken: He grew a mustache, he wore a mustache.

Voice: He was so proud of her cooking, you know.

Mixed voices

Skilken: This is interesting. Everyone ought to listen to this, talking about

Sanford Lakin. Everybody said he looked exactly like me.

Voice: He was so handsome.

Voice: He was a good-looking guy.

Skilken: And…

Voice: Everybody liked him. He had personality.

Skilken: He went out on the, he would go out on the market. At that time, by

this time, there was nothing on the east side market, just around the old market

house, you see. And every time he went there, he would stop at one stand and the

fella’ who run the stand used to call him “Moisha.” He said,

“But my name is Sanford Lakin.” “You’re telling me your name?

You worked for me as a kid. You’re Moishe Skilken.” (laughter and

conversation) Now he had, he worked for an attorney and this attorney was

training him to be the tax attorney in his firm. And offices either at 8 or 16

East Broad Street. My office was at 44 East Broad Street.

Interviewer: What year were you at 44 over Brown Drug Store was it? What was

the name of the drug store? I know it was a drug store.

Skilken: Barnes, Old Man Barnes.

Interviewer: Well I’ll tell you Sanford and Liz would have had a brilliant

career in this.

Mixed voices

Skilken: This attorney absolutely loved that boy.

Interviewer: And so did his clients.

Skilken: Yeah. And he was training him, like I say, to be at that time he was

assisting, beginning…(mixed voices) a tax attorney. Taxes were becoming

…part of the business. He and his partner come over to see me and we were

sitting there talking at my office. And all of a sudden this one attorney, and I’ll

tell you his name if you can remember. His brother had a men’s store on Rich

and High, on the southwest corner of Rich and High. Anyway…

Interviewer: Well the client was the guy that established White Castle

hamburgers, Ingram. That’s who Sanford was doing all this work for…

Skilken: All of a sudden this attorney begins to cry. I mean actually cry. And

I said to him, “I evidently remind you of Sanford.” He said,

“Yes, please excuse me for crying.” He was just that crazy about

Sanford.

Interviewer: What was the arrorney’s name?

Skilken: I can’t think of it. It was an Irish name.

Mixed voices

Interviewer: They were just getting the White Castle going, you know in those

years. And he found a lot of loop-holes for this Ingram. And that’s the family

that eventually, you know…

Mixed voices

Voice: When I got there and Sanford had died, I sat there and I cried and I

cried and I cried.

Interviewer: He was the only one we memorialized…That was Sanford

Lakin Memorial Award. That shows the impact he had on us.

Voice: I think at that time Ilonka had a store at Wilson and Oak.

Mixed voices

Interviewer: Sylvia, she was in charge of the dining room at the Neil House.

And he said he was so crazy about that food that he wasn’t going to let her

get away.

Mixed voices

Interviewer: She ran, they had a restaurant for a while in that apartment

house on Broad Street. What do they call it?

Mixed voices

Voice: We got to hear when he started with the community…involvement.

Skilken: At the old Schonthal Center. We used to have dances there. JFL club

had dances there on the third floor…got started because I had worked

with Boy Scouts for years.

Voice: Yes, I remember he was a Boy Scout leader.

Skilken: And then when my real involvement got with a, we called them Boy

Scout group at Schonthal Center. And what’s his first name, Goldsmith?

Interviewer: Dave?

Mixed voices

Skilken: He came to me and he said, “Morris, you always used to be active

in Boy Scouts. Why don’t you become, I got a Scout Master, Jewish fellow, but

he needs somebody to tell him what to do and show him how to do it.” And, what do

you call them…I’m talking about the Scouting movement. We had 132

troops in this area and I was introduced and I would become one of the so-called

leaders in the Scouting. I took this, and what was his name, I’ll tell you I

can’t think of the Scout Master’s name. Here we go again. Jewish fellow. I’ll

tell you what. His two sons were given scholarships at the Academy.

Voice: Munster?

Skilken: They had money enough, huh?

Voice: Munster. It wasn’t Munster?

Skilken: No. Anyway, within two years’ time they came to me and wanted me to

open up another Scout Troop. We had some Gentile boys from around the

neighborhood at Schonthal Center. It was really turning bad. And we had a couple

of tough kids in there. Well, I’d take those kids out in a hurry and within

two years’ time we had a full troop of 32. So they came to me and asked me to

open up another troop, start another troop. And I taught them real scouting.

Didn’t make any difference what the weather was. Could be raining. Could be

snowing. I’d pick kids up in a truck and if it was raining, I had a canvas

clear over the top. One of my company trucks. Put straw on the bottom. I’d

pick kids up at three different Sunday Schools and we would go out, sometimes as

far as 25-30 miles away, down in the hills. And I taught a lot of them to ride

horseback. I’d take them up to where I had a couple of horses up on the River

Road. And we really were scouting. We really did a lot. I’m talking about,

every kid had to prepare his own bed, his own lunch. Now…

Mixed voices

Skilken: Every kid had to prepare his own lunch and rarely did we get back

before 6:00 in the evening, depending on where we went.

Voice: Well how did you get involved with the Federation, how long ago?

Skilken: Well it goes back to the, I think I got involved with the Federation

through Heritage House. When they bought the people’s house on Woodland, I

got, we were doing nothing big work at that time and all union so I got a little

sub- contract, I got a little contract there. I think the whole job was $7800 or

$8000 in remodeling it. And my father had come up from Florida and was living

with us. But he was sad and lonesome, all by himself. Man kept strictly kosher.

And all of a sudden he says to me, he says, “I’m going into Heritage

House.” I said, “What do you mean?”

Mixed voices

Skilken: He said, “I’m going in there.” And I said, “What’s

the matter, aren’t you happy here?”

Voice: Don’t you like it here?

Skilken: “No.” Very, very lonesome. We’d go out to dinner. Fan and

I always did a lot of entertaining. We had guests in, you know. And he’d go

upstairs. He’d go to bed and just lie around. So we called Abe. And this was

soon after it was opened on Woodland Avenue.

Voice: Abe Wolman?

Skilken: Abe Wolman. Abe Wolman. And I’ll tell you about Abe Wolman…

Voice: Wolman was another…

Skilken: Yeah, we’ll get back to that. Like I say, every time you bring

something new, it brings another memory up, see. And we had 14 people there and

he joined when there was only six or seven. He went into there, ten weeks. And

we soon had a house full of 14. We had a couple that did the cooking. They were

refugees. They did the cooking.

Voice: Mrs. Steinmart.

Skilken: Huh?

Voice: Mrs. Steinmart.

Skilken: Was that the name?

Voice: Uh huh.

Skilken: I don’t remember the name. And he was happy there. He had somebody

to talk to. Everybody talked in Yiddish there, you see. And I mean, Yiddish was

their…If you couldn’t talk Yiddish when you went in there, don’t go

in there, you see, in the original house. And then, I think it was about that

time, before that. It was in the, oh I know when it was, when I first got

started. Ed Schanfarber, you asked me a question when I first got started. I met

Ed Schanfarber at the old Schonthal Center and he at that time was head of the,

whatever you called it at that time, the Federation, the Columbus Jewish

Federation.

Voice: What was it called then?

Voice: United Jewish Fund.

Skilken: United Jewish Fund back in the 40s?

Mixed voices

Skilken: Yeah, okay. So Ed and I were pretty close friends. Brilliant man. I

mean the community lost a, really a gem. when they lost Ed.

Voice: Died of a heartbreak.

Skilken: Huh?

Voice: I’d say he died of a heartbreak.

Skilken: 58 years old when he passed away. (Mixed voices) And he said,

“Morris,” he says, “I want you on my committee to,” he said,

“you know a lot of people. I want you on my committee.” That’s how I

got started in 1944.

Mixed voices

Voice: I was one of those who organized the Women’s Division.

Skilken: It was 1944 though, how I got. Been very active since.

Mixed voices

Voice: . . . . 1944 when we had the bond rally.

Voice: That’s how I got involved. That’s how I got involved with the

Federation, with the United Jewish Fund. They chose me as President of B’nai B’rith

Women to organize the Women’s Division.

Voice: You were the first President . . . .

Voice: No, no, Mrs. Kobacker.

Skilken: Talking about that, Jule Mark and I were the first two men…

Voice: Who?

Skilken: Jule Mark and I were the first two men, fantastic person, Jule Mark

and I, I’m repeating that, were the first two men who became members of the

Ladies Auxiliary. Remember when they started to take men in? Uh huh. Because…

Voice: Morris, let’s get to the building of Heritage House…

Skilken: Okay.

Voice: and what you know. You took the contract for the building of the first

floor. I’ll never forget how proud you were when we walked in that front

entrance, that on the ceiling you had wallpaper around the room like a frieze,

that had menorahs and everything on and you had picked that out someplace and

you had put that up there and and anybody who walked in, “Take a look at

that.” You were so thrilled and so proud what that thing implied. The

Jewish . . . . very unusual. It was done in gold and yellow.

Skilken: I do remember.

Voice: I always wondered whatever happened to that thing.

Skilken: I’ll tell you, talking, getting back to Heritage House we, within

60 days’ time, Aaron Zacks was appointed Chairman . . . .

Voice: Of the Campaign.

Skilken: of the Campaign.

Voice: Right, correct.

Voice: Aaron Zacks, Bob Weiler, Sr. and Abe Wolman.

Voice: Abe Wolman helped.

Skilken: Yeah. Okay. Now we want to design the thing. In 60 says’ time, I

run a cost and estimate on approximately what we wanted on a cubic foot basis,

on a square foot basis and I said, “Well, it’s going to cost somewhere

between $700- and $800,000.” Within 60 days’ time, we raised $800,000. Sixty

days. That’s all. Now then you have to decide. Everybody paid for their own

trip wherever they went. You paid for your own trips.

Voice: To go look at other homes.

Mixed voices

Skilken: So what’s his name, the architect?

Voice: Feinknopf.

Skilken: Feinknopf.

Voice: Yeah Mark Feinknopf.

Skilken: Mark Feinknopf didn’t know a damn thing about this type of

construction. He worked downtown remodeling and building store fronts and . . .

. like that. And did a really fine job of it. But he didn’t know a thing about

this type of construction. I think I was two, they took bids. I think I was a

couple of thousand dollars low or higher. I said, “I want to build it. I’ll

take it for a thousand dollars under the low bidder so legitimately I’m low

bidder and I’ll go on with it.” Who was the fella’ who had the, what

was his name who had the tire…

Voice: Katz?

Skilken: No, no, I’m talking about who had the…

Voice: Oh, Abel?

Skilken: Abel.

Voice: Yeah, Dick Abel.

Skilken: Dick Abel had a plane at that time, an old plane that would hold, I

think there were six of us…

Voice: He had a corporate plane…corporation, yeah.

Skilken: Six or seven of us, yeah.

Voice: By the way, that’s the father of the girl who’s working for you.

Voice: Betty.

Voice: Betty, yeah.

Skilken: Six or seven of us and we went over to New York to look at, they had

just added a hundred rooms onto a center, I mean onto a Jewish home for the

aged. It had 50 rooms or 60 rooms or something like that. Anyway they had added

a new addition. And I saw so many mistakes in that addition. Then I went to

Norfolk, Virginia where they had just built a new one. And I went to Chicago

where they’d just built a new one. And I came back and told Mark what the hell

to do. See? In fact, I designed it, see?

Voice: Maybe that’s why he was in so much trouble with the Resler end. He

was in plenty of trouble with that too.

Skilken: Well I straightened him up on the Resler one. I don’t want to get

into that.

Voice: Huh?

Skilken: I don’t want to talk about it because I’d be bragging about

myself.

Mixed voices

Skilken: Anyway.

Voice: I’m going to tell everyone that they should realize that the present

way we are situated, including the three floors which we are enjoying now, of

course it includes the Skilken wing, the whole Phase II, and God willing you

should be around for Phase III with me, is all, whatever we have accomplished

there we know would never have gotten done when it got done or gotten under the

prices that you got if it hadn’t been for you, Morris. You were the one who

made all this possible and the builders, the contractors and everybody keeps

saying, “I don’t know how Morris does it. But he’s the one that can get

anything we want.” If they needed boilers or some other equipment that had

to come in and they said they couldn’t have them for three-four months, he

said, “I’m going to have them here in 30 days.” And you had it there

in 30 days and it got built. And that’s the reason why it’s only a year and

two months since we broke ground. Not even a year and two months, about a year

that we have added this new Second Phase and wait ’till you people all see it.

You’re going to be overwhelmed. And the Third Phase, God willing you should be

around to continue what you’re doing Morris.

Skilken: Thank you. Anyway my brother and I, a double room cost $10,000, and

my brother and I…We were not in business at that time. We broke up in

1947.

Voice: Is that when you broke up, ’47? It was a long time ago.

Skilken: ’47. We broke up in ’47. And I’ll never forget the look on Mark

Feinknop’s face when we were under construction. Only a construction person

would have to appreciate this. Our doors are 3’4″ or 3’6″ wide by

7′ high, inch and three quarters solid. Absolutely solid. He had those doors

hanging on what we call the trim. Trim…trim. Nailed into concrete block.

I knew damn well that I couldn’t blame the architect. Morris Skilken was the

contractor. He should have known better. One morning I was coming off of the

south wing and I met Mark as he was coming in where the existing nurses’

center is. And he stopped and his eyes bugged open. I says, “Hi Mark,”

and I kept on going. Now why was his eyes bugged open and his mouth dropped? We

used what we called a “rough buck” to hang the doors on. In other

words, a rough buck. In this instance, our dividing walls for the hallway were

out of concrete block. So we built a frame out of 2X8’s. This is called a

rough buck out of 2X8’s and then we anchor that frame with metal anchors back

into the concrete block walls. Now when you hang your doors in, you put on your

frame, I mean your finish frame, is nailed onto this rough buck and you use long

screws then for your hinges so it goes through your finish frame and into this

rough buck. That’s only change number one that I made. How could I ask

Heritage House for an . . . . At the end of that place, I had to go down eight

feet to get down to good ground, solid ground and then bring the foundation up.

How could I ask Heritage House for a change order, which is legitimate. It’s

not in accordance with the Plans and Specifications. The first section of

Heritage House cost me my profit, just $15,000 that I took…

Voice: Besides what you gave?

Skilken: that I took, yeah, besides what I gave, besides what Joe and I gave

and that, this . . . . just leave that out. Please leave that out. Don’t put

that in there. I don’t…

Voice: I think it’s wonderful.

Voice: I do too.

Mixed voices

Skilken: Now you’re talking about, let’s talk about Phase II. Let’s talk

about Phase I. I made 23 changes to Plans and Specifications. And remember when

what’s-his- name, he had a beard…

Mixed voices

Skilken: Jack Resler used to call him “Rabbi.”

Voice: He was from Mark Feinknopf’s office.

Skilken: Yeah and he’s still a partner there. I mean he accepted every

change.

Voice: Is this on the current building program?

Voice: You mean the Resler building?

Skilken: That’s the Resler building.

Voice: Well Milt Staub was the Building Chairman.

Skilken: Yeah.

Voice: But you used to come to the meetings, remember?

Mixed voices

Voice: He did spend 24 hours a day on that building.

Skilken: I didn’t want to be chairman.

Mixed voices

Skilken: So we come along and one of the changes was this. The back was a dump

and it was all built, and I can remember it when we used to, I learned to swim

in what we called “three lakes”, three lakes down on Alum Creek. And

that’s where I learned to swim when I was 6-7 years old.

Voice: He was a champion swimmer.

Skilken: Yeah. And I can remember it was a dump at that time. So we’re

talking about 80 years ago. They had it designed for pilings and they had made,

I had asked them to have test soil bearings, test soil borings made. I look at

it, and here’s where your sub-plot engineer comes in. I says, “Nope, you

got to change this.”

Voice: It was a dump.

Skilken: It was a dump.

Voice: Bexley dump.

Voice: Bexley dump, yeah.

Skilken: And I says, “Now this is old,” how many years was it

since we built the Resler wing?

Voice: About 1972, ’71.

Skilken: l972, ’71. Which was, let’s see…

Voice: About 16 years ago.

Skilken: Anyway, whenever it was.

Mixed voices

Skilken: And I said, “Nope,” and I went back to the office. At that

time I had some architects working ’cause we were doing a lot of bill design

work, and redesigned it, excavated down to, listen to this, just a moment, then

you can talk, excavated all of this out. Eliminated down to solid ground,

eliminated the piling entirely and we will build walls in here and have all of

our plumbing done for another floor. I says, “And while we’re at it, we’re

going to design the footings large enough, heavy enough to put a third floor

on.”

Voice: Support a third floor?

Skilken: Yeah…

Voice: Let me…when Morris came in with this idea of

supporting the third floor with the pilasters, I remember the term because I’m

not a construction person and we realized it would cost naother $17 or $18,000

…

Skilken: …thousand dollars.

Voice: Well that was, you said around $18- at that time. I don’t know what

it finally cost. And Jack Resler said, “We’re going to do it.” And I

said, “We can’t raise any more money.” And he said, “Damn it.

if we’re going to do it, we’re going to do it right.” Remember? And

Jack said, “I’d go along. If you can’t raise it. I’ll give you the

money and we’re going to make that strong enough.” So a third floor went

on and I…

Voice: …exactly four years after the Resler Wing was completed, 50

rooms, we needed fifty more rooms. and we had the 50 rooms ready down there. We

had all the . . . . in, you see? All we had to do was put in the petitions and

we did it for half of what it would have cost. And then, this was where the

Skilken Wing come in then . . . built that third floor with. You know, I still

feel embarrassed when people refer to it as the Skilken Wing.

Mixed voices

Voice: I think you’re entitled to it with all the work you’ve done and

everything.

Mixed voices

Skilken: Now we had the…the Torahs…when we moved out of the

old house on Woodland, we took the Torahs over to the Center and that was really

a beautiful affair.

Voice: That’s right.

Skilken: And Sam Schlonsky led the way with the first Torah and I don’t know

who carried the other ones.

Voice: …

Skilken: Huh?

Voice: You carried one of them.

Mixed voices

Voice: We’re going to have another ceremony in another year and a half.

Voice: Morris, how long do you think it’s going to take for us to get the

30 spaces filled?

Skilken: A year, maybe less.

Skilken: No, no. Oh, no, no, no, no. I’ve already told them not later than

June the first, you see?

Voice: Are we going to have 50 or 100 more rooms?

Skilken: A hundred.

Voice: You sure?

Skilken: A hundred more rooms.

Mixed voices

Voice: ‘Cause 50 rooms for very ill Alzheimer’s and totally-ill people

will be in that area who have no other place to go. And we’re going to have a

lovely synagogue in another section.

Skilken: Yeah.

Mixed voices

Voice: It’s going to be much prettier than what we have now.

Mixed voices and a slight blank spot on tape.

Mixed voices

Skilken: Let’s talk about Phase Interviewer. A year ago the architects sent

over what we call a line drawing and they were laying on Nick Boslovick’s

drawing table and I went in to look them over. And I’m looking and I’m

looking and all of a sudden I says, “What the hell is this?” The

dimensions weren’t on so I took a scale and there was a room 6400 square feet

for staff dining. Finally he helped me figure out three shifts, what we’re

going to need for staff ’cause there’s three shifts for 250 rooms. We’ve

got 150 rooms now, for 250 rooms. And I added another 50 in case we put on

another 50 rooms, another story. And I come up with 1800 square feet.

Voice: Plenty.

Skilken: Huh? That’s all we needed. So I said, “Okay Nick, let’s go

to work.” The architects were told, “Give the staff anything that they

want.” They don’t have any idea the size of a room. So they said,

“Well no we need this much room, this much room.” Nick and I went for

eight straight hours. There was 216,000 square feet that the architects had and

we knocked off 66,000 square feet.

Voice: And it’s still huge.

Skilken: Now, and I says, “Okay Nick.” Called the architect into the

office. Now we’re going to give the staff everything that they wanted with

this 66,000 square feet knocked off. We made an appointment with Jerry and Bill

Bloom and the whole staff. And I said, “Nick, I don’t want to be there

because I’m liable to lose my temper at some of the staff members. Here take a

ball of twine with you and some blue chalk and I’ll have Dell Hume clean out

space in the,” what do you call it where we teach people things?

Voice: In the O.T. Room.

Skilken: Yeah, Occupational Therapy … “Strike a line.” We cut

all the rooms down in size to where they were supposed to be. Had enough

meeting. Supposed to meet at 9:00. I figured it was going to talk all day and

maybe another half a day. Nick walks into the office at a quarter after 12. I

said, “What the hell you doing here Nick?” He says, “We’re all

done.” “What do you mean ‘you’re all done’?” He said,

“We satisfied the staff on the size of the rooms that you put up for

them.” Saved two and a half million dollars! Heritage House wouldn’t be

being built now if we’d have had another two and a half million dollars on

there.

Mixed voices

Voice: We’ll add to this another day.

Voice: All right.

Tape clicks off and on.

Voice: Everybody on that ward, you have never seen more dedicated people, men

and women, that you’ll find on that Heritage House ward. In fact, I think

other . . . . agencies are jealous of what we do and what we accomplish.

Voice: Who?

Voice: All the agencies are jealous of our ward. Our ward is the most

dedicated, once they get on the ward, they become so involved. . . . . himself

is the leader. He has the knack in a very quiet and very sophisticated way of

commanding respect and dedication from the people he works with. And I think

this is the answer. He has that same knack with his staff. When you find a place

like this that has staff that stays 16, 20, 14 years constantly, he brings them

up through the ranks. He takes a little girl and he ends up with her being a

real asset in a very fine position. He has a way of very quietly getting the

best out of you. He does the same thing with the Board. And this is the whole, I

think this is the whole, it’s a matter of loyalty and of sincere respect for

what they can do and what they accomplish. And the staff has that same atti—.

I was with a woman as I was walking out today who’s taking care of my aunt.

She’s a new girl who came to work for her, Mrs. Margulies. And she said,

“And they’re complaining about this and they’re complaining about that

and,” she said, “without me saying a word” . . . . And Ruthie’s

sitting there and you know what I’m talking about. And she said, “I have

worked for 34 years in the nursing business. I have never been in a place as

wonderful as this is. And as wonderful as they are to staff.” Now she said,

“They respect you, they say ‘Hello’ to you. You’re not an underling

and,” she said, “they make everything of the finest available to you

and it’s a joy to work here.”

Voice: How many women are members of the auxiliary?

Voice: Auxiliary? About 1400.

Voice: 1400?

Voice: I don’t know any more. I’m not involved like I was.

Mixed voices

Voice: . . . . it’s really a nursing home. The way we do it is like we call

it the Tower and we have what we call the special needs unit. (Mixed voices)…

the Manor and the day care program. And wait ’till you see the size of our

day care area. Now that will be a non-segregated area. The other thing’s all

Jewish but the other agencies are for everybody and I’m going to tell you

something. The next project, and it’s in the works, once we get through with

this. I can’t push this back too much. Our next project is to have a place

like Heritage Tower, only for people who can afford it. You’ve gone through

that. This is how you do it. You have different levels of care and that’s…

Voice: And my further question is, and this is a long-range thing, how do you

begin in middle life, let’s say, to teach people to prepare or to be

independent?

Voice: I’m at the age now where I’m concerned…to keep my

independence. I don’t want to be a burden to my daughter.

Voice: Oh, our generation is that way.

Voice: I figure there must be things we can do to prepare people.

Voice: Well I’m going to tell you something…

Tarshish:: I had one friend who’s at Heritage House. I won’t mention any

names…But she has always been a leaner all of her life. And when she got

to, she’s younger than I am, and when she got to the point of her children

being away, she just fell apart, and so that was the easy solution. Her children

don’t have to worry about her…

Voice: Well you know something Mildred, there are many kinds of people in the

world.

Tarshish:: I know.

Voice: And you can’t prepare for any one…’cause there are

different…

Mixed voices

Voice: But I’m going to tell you someting. It’s what you do with your

life and I’m finding that most of us in our age group are really independent.

Our group that grew up, it will be much longer from now, it will be when we’re

in our late 80s that we’re going to find ourselves needing…

Mixed voices

Voice: That’s a different group and I hope that one of these days they’ll

find an answer to it.

Mixed voices

Voice: …are meetings for these things. If we could get the

participation of the people so that they could become acquainted with how to

take care of themselves and how to be independent and how…don’t have

to worry. You know why?

Mixed voices

Tape ends

* * *

Transcribed by Honey Abramson