Louis Robert Polster

INTERVIEWER: Today is Wednesday October 9th, 2013. I am Linda Kalette Schottenstein interviewing Dr. Robert Polster for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society Oral History Project and thank you so much for agreeing to be interviewed. I have wanted to do this for a long time.

POLSTER: You’re very welcome.

INTERVIEWER: Ok. So, what is your full name and birth date?

POLSTER: My name is Louis Robert Polster and I was born June 18, 1942.

INTERVIEWER: And were you born in Columbus?

POLSTER: I was born in Columbus at Grant Hospital. My parents at that time lived in Bexley and I’ve been a Bexley resident almost all of my life except for several years spent in Columbus.

INTERVIEWER: So, how far back have you been able to trace your family?

POLSTER: On my father’s side we are able to trace our family back four generations. Some other family members have done some very nice genealogical work to help us understand how the various families that came from East Central Europe in the Carpathian Mountains of Slovakia today, the old Austro Hungarian Empire, how they all interacted and intermarried, Schlezingers, Polsters, Gutters, Wasserstroms, Friedmans, these families and a few others had many interlinking marriages over the years and it made quite a large family much of which settled in Ohio.

INTERVIEWER: Do you know who the first people were in your family on either side to come to America?

POLSTER: Yes, on my father’s side it was my father’s father after whom I am named, Louis R. Polster. He came to the United States at the age of about 16 by himself. The family history is such that his father whose name was Leopold, who never came to this country, died in what is now Slovakia. He had his first wife, prior to my great grandmother, and she had at least eight living children who immigrated to the United States eventually. She died with her 8th child in childbirth and my great grandfather remarried my great grandmother who, as his second wife, bore him at least five children that we know of, all of whom settled in Columbus at one time or another. And so that was the first generation. My great grandmother came at the very end of her life in 1914 or so to America, lived here for one or two years in Columbus, and is buried in the Tifereth Israel Cemetery.

INTERVIEWER: And her name?

POLSTER: Her name was Hannah. My grandfather Louis Polster had his brothers and his sisters here in Columbus and the other half of the family, if you will, the children of the first wife settled in Baltimore, New York, mostly in Cleveland and Cincinnati. Through the many years and generations we’ve more or less interacted and there are now members of that family in Columbus, particularly Geri Ellman, whose maiden name was Polster and is a cousin who is from that side of the family. Growing up I really didn’t know that Cleveland half of the family very much because for my father these were all half first cousins and there wasn’t much inter-relationship. There was a big enough family already here in Columbus, I think, that they spent most of their time with. My grandmother on my father’s side, her maiden name was Hibschman [Anna Hibschman] and she was from Cleveland and before that I don’t really know exactly where she was from. She was gone before I was born. And they gave birth to eight children all of whom grew up in Columbus. My father was the second of eight, Lawrence Polster. His older brother Toby [Tobias] was the oldest and the two of them were pretty close in age. They were 15 or 16 months apart. And then the family spread out over several years. We are currently in the home that I’ve obviously been in for some time now in Bexley but the prior owners included my sister who owned this house for many years and before that my Uncle Martin Polster, one of my father’s brothers owned it for many years so the family has stayed close to Bexley in Columbus since 1920.

INTERVIEWER: Do you remember hearing any stories about their coming to America?

POLSTER: The story that I remember is of my grandfather – I don’t really know much about my grandmother except having seen some pictures, actually moving pictures of her but my grandfather came alone. He had a half-brother from his father’s first wife who had been living in the Cleveland area but had moved south to push a pushcart and to peddle in the small Ohio communities and to my knowledge when my grandfather arrived, not in New York through Ellis Island as so many people came – Baltimore, Fells Point is where his ship landed and he was given a piece of paper that was sent to him which had in English on it “B & O Railroad, Circleville, Ohio” and some money for a ticket and he took that train from Baltimore to Circleville and got off the train and his half-brother, whose name was Moshe, met him and set him up in business at the age of 16 or so. I’m not really sure about his education after that. I don’t really think he went to school at all. I think he just began selling at that time what was called “queensware,” now thought of as pots and pans and dishes. First they were peddlers. My grandfather came to Circleville in 1885. After working and peddling around south central Ohio, he married and settled in Circleville. My uncle Toby, Tobias, was born there in 1897 and my father Lawrence followed in 1899. The family moved to Columbus shortly after that where my Uncle Nate, Jacob Nathan Polster, was born in 1901. The occasion of his bris was also the occasion of the founding of Congregation Tifereth Israel, a story that many people have told and have heard. So that was my grandfather on my father’s side.

My mother’s parents immigrated from what is now Russia or Byelorussia [Belarus]. It was a town of Swir at least where my grandfather was from. I am not sure where my grandmother was from but I suspect close by, and I think they came together to New York in the 1880’s and stayed in New York and I don’t know anything about the family beyond my mother’s father and mother but my grandfather in New York was a businessman who had a friend, one had a horse and one had a cart and so they went in to the funeral business so they could cart the people to the cemetery from the funeral homes. My grandfather then had the privilege of being the first licensed Jewish undertaker in the city of New York and the chapel is still there [Sherman’s]. I have cousins to this day that have it. They moved from New York to Brooklyn in the early 1900’s and the family’s been there ever since.

INTERVIEWER: Your grandparents, they married…

POLSTER: I don’t know where my grandparents, where my mother’s parents married. I am not aware of it.

INTERVIEWER: Your parents, how did your parents meet?

POLSTER: My parents – that’s a romance story. That’s the kind that they write dime novels about because my father and his cousin Sam Melton had decided to take a trip to Florida in 1934. I believe it was 1934, might have been the winter of ‘33-‘34 and my mother at that time had taken her father to Florida because he was ill and he needed to perhaps escape the winter so she was in Florida and as the family story goes, my mother was sitting on the beach on a towel and Sam Melton and my dad, Lawrence Polster, were walking down the beach and I don’t know if they flipped a coin or not but my father won the toss and went over and talked to this young lady sitting on this towel and four dates and seven or eight months later they were married. And that story is one of those stories of how do you allow – I mean my mother was 25, my father was 35 so there was a big age difference and how do you allow your daughter who’s never been west of New Jersey probably to think about marrying someone and moving to Ohio. They didn’t have computers, didn’t have services of that sort in those days so my grandfather in New York sent his two sons to Columbus, Ohio without telling anybody they were coming to check out this Polster family to see if they really were in business and they really had some resources and if they were really taking a risk in letting their daughter marry in to this family far, far away. So my two uncles came to town and asked around to see who was knowledgeable about this family and went back and I guess they must have reported favorably but my father’s father was very upset by this whole thing, apparently, so he sent two of my aunts to New York to find out about the Sherman family to see if they were [ok] so there were these back and forth reports that my parents didn’t apparently know much about any of these visits until later on. But they only met three or four times together before they decided fairly quickly to get married and they were married in November of 1934.

INTERVIEWER: Where were they married?

POLSTER: They were married in New York. I can show you a picture of the wedding I think it’s downstairs. You can’t see pictures on a tape but I do have a picture from that wedding dinner that was taken in Brooklyn, New York and many of my father’s family are in that picture, of course, because they all went in for the wedding looking as very young people in the 1930’s. Course I didn’t know any of them. I was born in the 1940’s. So, that was the story of my parents’ meeting and their marriage. . When my mother came to Ohio this was a really brave step for her. She was thoroughly New York. She’d grown up in the twenties. It was not unusual to go to places like the Cotton Club and do those sorts of things for her. She was fully immersed in New York life and she was moving to this backwater of Columbus, Ohio, but she never looked back. She made this her home.

INTERVIEWER: Do you know where they lived?

POLSTER: Yeah, they lived, I don’t exactly know the location but they lived in an apartment for three or months while the house on Powell Avenue in Bexley was being finished. My father built that house and they moved in to it in early 1935. They were certainly in to that house already by the time my sister was born about 13 or 14 months after they got married.

INTERVIEWER: In your immediate family you have…

POLSTER: In my family I have two older sisters and I’m the baby and my sister Susan Polster Katz was born in 1935. My sister Kayla Polster Van Norman lives in California was born in 1938 and I was born in 1942 and so that’s the core family.

INTERVIEWER: So, talk a little bit about your early life then growing up in Columbus what you remember.

POLSTER: Well, I grew up really only about four or five blocks from where we are sitting right now. This was my neighborhood. I grew up on Powell Avenue between Cassady and Dawson so we’re just a few blocks from there now.

INTERVIEWER: Do you remember the house number?

POLSTER: 2459 Powell and I lived in that house from my birth until 1958 when my parents decided to sell the house. It was a two story house and they decided to move in to a one story home so we moved to a home on Frances Avenue in South Bexley and they were there from 1958 or until about 1985 or so when they moved out of there. That was a brand new home that had just been built. So my father built the house on Powell Avenue and moved in to it a year or so after it started construction and I grew up on that street. It was just a wonderful place to grow up. There were other children my age in the neighborhood and so there were plenty of people to play with. I only have fond memories. We had cherry trees in the back yard and I used to climb the cherry trees to pick the high fruit. My sisters would pick the low-lying fruit as they say and I was the one nominated to climb up the trees. My mother always had nice gardens and plants and some vegetables and things that she would grow. We had a fully fenced in back yard and the neighbors on either side of us that were always friendly and loving so it was just a great place to grow up. I began school at Montrose in kindergarten, the only kindergarten in Bexley then in 1947/1948. The teacher was Miss Barbara Drugan. Everyone knows of her as Miss Barbara. Interestingly she had been a student teacher and the teacher failed to show up so they gave her the job. At least that’s the story I heard and she took that class over I was in her first class. Interestingly, as time passed and we can talk about my marriage and my family growing up in Bexley, but all three of my children also had Barbara Drugan as their kindergarten teacher so it was a nice transition. She was a real important part of our lives even afterwards. So I went to Montrose that first year. Then I went to Cassingham for 6 years, at Cassingham Elementary School, went to the Jr. High as it was then called and then to the high school, so I stayed right in the complex for all of my school years. During all of that time until 1958 we lived on Powell Avenue and it was a four block walk to school, went home for lunch every day. I think I probably only ate at school three or four times in 12 years or 13 years ‘cause every day there was lunch waiting for me at home. My mother did not work outside the home although she volunteered a lot, did a lot of other things and so she was always there for us whenever we came home.

INTERVIEWER: What was she involved in?

POLSTER: Oh, synagogue Sisterhood, Bnai Brith Women, Hadassah, all of the usual organizations, Jewish Center activities and she was a driver for, I can’t remember what they called the organization, but to drive people to their treatments for cancer treatments. It was a Cancer Society program and so she volunteered to do that and she volunteered to do other things in the community of a service nature. She was active in many, many types of organizations of that sort as were her generation. This was a story we hear of all those people who did all those things we now pay people to do. They did happily most of the time.

INTERVIEWER: So you grew up with Jewish kids and non- Jewish kids?

POLSTER: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: And was there ever any anti-Semitism that you felt?

POLSTER: You know I heard about it more than I felt it. Again, I was born in 1942. I don’t remember 1942 although I can look back and hear stories about what life was like in the, during the War years. I became aware of life in the post-War era. I became enamored of anything gung-ho Marines by the Korean War. It looked like war was the best place to be and the most fun thing to do. You didn’t want to play Cowboy and Indians, you could play soldiers and it wasn’t until another generation that I found out how unpleasant war can really be but that’s another story. We did have Jewish and non-Jewish friends alike, mostly Jewish contacts. My family was always heavily involved within in the Jewish community in one way or another and synagogue life was really, really important for us. I sang in the Youth Choir at Tifereth Israel at the age of seven until I graduated from High School and sang in High Holiday Choirs. My mother was one of the Columbus founders of United Synagogue Youth, USY. She came back from a Sisterhood, it was actually a national Sisterhood meeting with this idea with two other women and they said, “Let’s have a chapter here.” In fact, my older sister Kayla went with USY to Israel in the very first youth trip or aliyah or youth pilgrimage or whatever you want to call it from the United States to Israel in 1956 when Israel was only eight years old. She went with USY so by the time I came along a little later that was a very important part of my life as well and I went to the national conventions in four different years. The impact of that, the organization really brought a lot of Jewish kids together and things. Then there was the Bexley Schools, which integrated us all. Bexley was never a primarily Jewish community although if you talk about stories heard my father told me that when his family moved in to Bexley in 1920 and built one of the first 5 Jewish homes and their home was at the corner of Fair and Drexel – Bexley was then called Little Jerusalem because five Jewish families had decided to move there. At the same time some other people of means were moving to a place called Upper Arlington which was apparently nick-named Mortgage Hill because all the bankers lived there and so these were the kinds of ethnic divides. But you ask about anti-Semitism and it was just known in my generation being say between the ages of seven or eight when I had a bicycle already and high school years ten years later, and it was just known that you didn’t ride your bike in certain streets in North Bexley because there weren’t any Jewish people there and you weren’t welcome on streets like Ashbourne and Northridge and those sorts of streets. You just knew that. It was common street knowledge. You certainly didn’t go to Sessions Village because that was apparently built, as we were told, by people who really wanted to separate from everybody else. You didn’t go there. There was no Jewish Community Center. There was a Schonthal Center when I was younger. I remember going to the ground breaking ceremonies. My father took me to the groundbreaking ceremonies for the Jewish Center in 1949 and I still remember being there and listening to the speeches and watching the people up front. Recently they had pictures as part of the Center’s 100th anniversary celebration, pictures of those ceremonies and I looked. I couldn’t’ really find myself but I could find where we were sitting. Chairs were empty in the picture. And that was a very important institution for this community and for many in the Christian community because the Catholic kids didn’t have any place to go play either and when the Jewish Center actually opened in 1950/51 there was a surge in non-Jewish membership, mostly from Catholics. We had Catholics on our Little League baseball teams and basketball teams and so forth. They were all thrilled to have a place to go and a place where they could swim and that sort of thing as well. So that’s among my memories about inter-religious activities. I think we integrated as much both in school and through the Center as anywhere else but I never really felt the pressures. No one stopped you in the street or called you bad names or did those sorts of things. We just all knew that there were certain rules and we played by those sets of rules and everyone sort of got along and we didn’t always have kind things to say about any other group but that’s nothing new. They didn’t have very kind things to say about us sometimes, too. All in all growing up Jewishly in the 1940’s and early 1950’s was not the difficult problem that is was for the generation before. We were not the immigrant generation of our families. It was just America and we were part of it.

INTERVIEWER: There are a lot of pioneers in your family who have done a lot of firsts.

POLSTER: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Can you talk a little bit about your life surrounding the synagogue?

POLSTER: My grandfather was one of the original signers of the charter that formed the First Hungarian Hebrew Congregation of Columbus and they were called Hungarians. The story is told, and again these are just stories handed down, that their Yiddish was not of the same quality and caliber as the Russians who had immigrated and were the predominate members of the one major non-Reform synagogue in the community – Agudas Achim – and so they didn’t get along very well. They spoke with funny accents, maybe had slightly different customs and were made to feel unwelcome and so that led to the founding of Congregation Tifereth Israel. My father and his brothers were all integral parts of that congregation from their birth practically. My father was two years old when it was founded and I think I’ve had nine relatives if I include the husband of the interviewer who have been president of Tifereth Israel over the years.

INTERVIEWER: So, talk about your, how it felt being president and what it meant to you.

POLSTER: Well, first of all I got involved when my brother-in-law was president of Tifereth Israel. Actually before he was president he asked me to begin serving on a committee. This is Marvin Katz. Marvin and my sister Susan had married in 1953. This was now in the 1970’s and he had been sort of impressed into service to be an officer of the congregation. There was some rapid turnover, someone moved to Florida, I remember, and someone else decided not to be an officer and Marvin suddenly found himself president of the congregation. And at that time he asked me to be on the Board of Education and that’s where I began actually getting involved in the congregation. Prior to that time I had been a member, actually paid dues from the time of my marriage in 1964. You got one free year so I didn’t have to pay until 1965.

INTERVIEWER: Still do.

POLSTER: And we kept up our dues payments even when we were out of town for a little while and so forth. We always stayed members. My wife and I have been continuously members ourselves since 1964. But by the mid 1970’s, and I don’t remember the exact year, I think it might have been 1975, I was on the Board of Education and ultimately became chair of the Board of Education and I did that for about 5 years and from that I moved into the role of being an officer and after a couple of terms as a second vice president and couple of terms as a first vice president, actually, was actually passed over a couple times and then took my turn as president in 1987-1989. During that time were all sorts of things from the recruitment of Rabbi Berman to ultimately Cantor Chomsky, actually recruiting the people before them, and dealing with those kinds of affairs. I’d served on the personnel committee from an early time and so I was involved with those sorts of things but really not involved with the philosophy of the congregation until after I became chairman of the Board of Education but being a chairman of the Board of Education of a school which had external backing was really very powerful and important – a learning lesson or me, having to balance the wishes of generous donors with the needs of the congregation. Those are skills that you may be born with and sometimes you have to develop them. It was really good as a growth experience for me and I had wonderful people to work with. We had had by that time many years of a rejuvenated educational program thanks to the generous donations of Sam Melton. And we had people who were sent to us to our community, basically to be teachers in our school. Our school was really invigorated by a fellow by the name of Sol Wachs and the people he brought with him. Anne Bonowitz is still in the community as an example of that. She married and stayed here and became an integral part of our congregation forever, but what happened just before I got involved with the Board of Education was a growing interest by parents in having their kids have a broad Jewish education and not just a narrow let’s-learn-for-your-bar-or-bat–mitzvah but let’s also learn about our culture, our history, our sociology, and in America and Israel and in the world and so the school was just a very vibrant place and kept growing every year. The Hebrew High School would graduate eight or ten people every year which was good because it was not open to the whole community at that time. These kids in order to go to camps like Camp Ramah would have to stay involved in education as one of the criteria, things that we put in place and so we saw this living and learning Jewishly that really has carried over into many communities now where people from Columbus have migrated and so that was really a most exciting and worthwhile part of what I did at Tifereth Israel in the education area and then the whole responsiblility of officership and helping to guide the congregation ultimately succeeding to the presidency just at the time when it was decided we would raise three million dollars and we’d redo the synagogue. So, in my presidency I went to 5 meetings a week usually in the mornings and I was the only non- business or contractor person in those meetings usually, because I had to represent the interests of the synagogue directly and purse of the synagogue, as well. It was really a wonderful experience because the people who came to those meetings, they just didn’t know how to generous enough with their time and their thoughts and so it was really a very exciting time, 1987-89. We remodeled the congregation and the remodeling held up for about 25 years so I’m very pleased with that but it was a difficult time to be president of an organization because we were asking everybody for more money than usual as well as their time and their energy and efforts. Interesting things happened during all that and I really learned a lot about how charitable people can be and how generous they can be given the right causes. So, that’s pretty much my life with the synagogue. I’ve been a fairly regular attendee. I sat on the bima for close to ten years altogether so it was nice to come down and be on the other side of the bima and we still enjoy all of our activities. As I backed away a little bit my wife has moved in to her role as a teacher in the school and she’s now been doing that for over 13 years, I think. This is her 14th year of teaching, I think, so we are still involved.

INTERVIEWER: I want to get back to her and you but go back to after you left school in Bexley.

POLSTER: Sure, so, my life. Alright so in school in Bexley I met a few friends who were really interested in pursuing higher education in a serious way and I became, because these were my friends, my good friends, I became interested in medicine and I went to my parents when I was a sophomore in high school and said “Mom, Dad, I think I want to be a doctor.” Now, at the time I didn’t tell them that I was searching desperately for anything that would tell them I didn’t want to sell pots and pans and I didn’t know how to tell them that, but what I found out when I had made that announcement was that my father was only staying in his job for me and there were obviously other family reasons, as well, but by that time, by our counts, he’d already worked in the business 47 years and that was enough for a career so he was ready to do something else and the day after I came to talk to my parents about this, with much trepidation, thinking that they weren’t going to be very happy, my father went in to see his brothers and told them he was selling out. He was retiring from the business and that was practically his last week of being in the Louis R. Polster Company. I have some stories I can tell about what it was like to be with him before that if you are interested but I want to go ahead with this now, to follow this train of thought. So, I picked medicine and I had no clue what I was getting in to. I just knew that all the smart kids in school were going to do something like that. They were going to be doctors or lawyers, or engineers or chemists or something and I should pick something, too. I knew I didn’t want to be a rabbi, didn’t want to be a lawyer so the only thing it seemed left to me was doctor and in pursuit of that I paid a little bit more attention in things like chemistry and physics, tried to do a little bit better and then finished high school. I decided to go to college where my middle sister Kalya had gone to college and that’s Ohio University. You didn’t get very far from home in those days. I am a Bobcat but only a half a Bobcat. So, in 1960 I had a close friend from my high school days by the name of Steve Levy and Steve and I both enrolled at OU and went there. Steve was, and I want to mention this just a moment, he was one of the few people that I ever knew that got perfect grades on his college boards, on his SAT exams. He missed nothing. In those days it was 1600 and they didn’t have the third piece that they have now. And he was recruited by Ivy League schools and so forth but had decided to go to Ohio University after he received a letter saying he had an appointment to West Point if he wanted one. He could go to the Military Academy. And the reason I bring this up in this interview is that he and I went to West Point with his parents to look at it. And he got to West Point and he said – and he was not a person who was overly enamored of his religion. He was culturally Jewish that was about it, but he said “Where’s the Jewish chapel?” and they said “Well, I’m sorry but we don’t have enough servicemen for a Jewish chapel. We do have a Jewish service.” He said “Where is it?” “Oh, it’s here in the Protestant chapel and they have it every Saturday.” We went in to the Protestant chapel and it didn’t look very Jewish and he said “Is there anything that they do to the décor of the chapel to make it feel a little bit more comfortable for the Jewish servicemen?” and the officer that was showing us around said, “Yes, you see this cloth that hangs over the lecturn. That’s a purple cloth that they use in the Protestant services there. You turn it over and there’s a Jewish star on the back of it.” And my friend Steve took one look at me and said” I don’t think you can be very Jewish here.” And he went to Ohio University, turned down the appointment to West Point, so it was just interesting ‘cause that was 1959. Put some context to it and it wasn’t that there was anti-Semitism at the military academy or anything that we knew of but something told the smartest guy that I’ve ever known that it wasn’t the place for him and so off to OU we went. Had two of the best years of my life at Ohio University in terms of having fun, meeting new people, activities, good courses, everything was good there and then left OU to come to Ohio State. Next subject: Why did I leave OU to come to Ohio State?

I fell in love. When I went off to OU I was as a college freshmen, fell in to all the things that you could do at a university, came home on Thanksgiving and my friend Steve said, “I know this girl who’s just moved to Columbus. Would you like to go on a double date?” And I said, “Well, I don’t know her, I’ve never met her, I don’t know anything about her.” “It’s alright because my friend that I’m dating says that she’s really nice.” And I get in my car to drive over there and he calls and says before that “I’m sorry we can’t go.” So, I go over and knock on his door in Eastmoor and I met for the first time my future wife without knowing she was going to be, that we were a blind date and we were fixed up. We went out, we saw a movie. I can still remember the movie. It was called “The Robe.” It was an Academy Award nominee movie of its time. This was 1960, and went home, had a terrible time. She said that all I did was talk all night long and all I thought was this was the quietest girl that I’d ever met in my life and thought that was it, that it was all over but I came back home during holiday break and I said maybe I’ll call her. Maybe I’ll give it another try. Maybe I’ll call her because I didn’t really have anything else to do and that was the moment the spark was lit and we’ve been a couple ever since now for the last 53 years. At that time she was still in high school. She was a high school junior and I mention this in the context of OU because her parents actually allowed her to come down to Ohio University for a weekend and, after we’d been dating, she was a senior by that time. I presented her with my lavaliere, I think it was, from the fraternity, and she was serenaded and she was on a balcony and the entire fraternity was singing to her and it was one of those moments that just melts your heart and she became a part of that group as well, with us although she never went to OU. So, that when she was going to off to college in 1962 I decided I didn’t want to be away from her anymore. I transferred to Ohio State and I finished my undergraduate work in December of 1963. At that time I had applied to medical school at Ohio State and a few other places and had had an early admission interview at Ohio State but had no good idea about whether or not I was going to be able to go there and be accepted. And to put this in the historical context, 1963, the Cuban Missile Crisis had just happened. The status for unmarried men was you were in school or you were drafted, or you were married. Those were the choices and so in order to stay undrafted and I’d received a draft notice. As soon as I graduated I received a draft notice: “Greetings from Uncle Sam, Come Private Polster and join the army” and I didn’t want to do that. For one thing I was planning on asking my girlfriend to marry me that New Year’s Eve. For another thing I wanted to go to medical school not the army and so I went up to Ohio State and I enrolled as a special student, not a grad student, but a special student and I took an enormous number of hours. I think I took nine courses and you were only allowed to have five or something like that, but they didn’t stop me from enrolling in all these courses and I just had the most wonderful quarter of a time until January 15th when the announcements came out that I was accepted to medical school so I finished that one quarter and just really had the best time educationally ‘cause I didn’t had no pressures on me anymore. So we did get engaged New Year’s Eve 1963/64. We got married in August of 1964 so we were married while my wife still had one or two years left of college and I was about to enter medical school and she was 20. I was 22. We look at what people seem to do today and they seem to get married a little older than that. We didn’t know any better. Actually I have, my oldest sister was married when she was 18 so waiting until I was 22 years old was actually being a little, you know. So then I spent four years of medical school at Ohio State. During that time we had our first child born. My wife was a teacher in a public school starting in 1965 and I remember what that felt like because I had managed to earn some money and saved up about 25/2800 dollars which was what we lived on the first year we were married. We lived in student housing. I think it was 79 dollars a month or something like that, including heat, and we would be able to eat at the local McDonald’s and get 3 cents change for our dollar and so we sort of managed to get by and then when she graduated from school and began to teach we were rich as could be. She was making $5200 a year and we couldn’t believe how much money that was but she did continue to teach until our first child Debby was born. I was in medical school at the time and then after medical school I toured around the country, the two of us, well three of us ‘cause Debby went with us, toured around the country and looked at nine or ten different locations for internship and residency in pediatrics and we came back to Columbus after looking at all these other places deciding that what we had in Columbus was as good if not better than what we saw, and so we settled in and I did my internship at OSU and Children’s Hospital. I did my residency at Children’s Hospital. I entered Fellowship at Children’s Hospital in Community Pediatrics basically taking the health care system out to the people that were most disadvantaged and, in the midst of that, while I just had a few months left to finish so that I could actually go out and practice on my own, I was again served with notice from the Army and this time it was Viet Nam and now it was 1970 and at least I went up in rank from Private to Captain. So this time they were taking me in as a Captain in the medical corps and there really wasn’t getting around this one. It worked to get in school in 1963 but there was nothing that was going to keep me from this. In order to finish my medical school I was a junior in medical school we had choices and one of the choices that we had and that was, junior in medical school this was 1967. I want to put this in historical context because of what was going on internationally with the US at war and we had a choice. We could just take our chances and they could pull us out of medical school at any time and draft us as Privates or we could sign a piece of paper which made us something the Army could only come up with this term, an Obligatory Volunteer. I was obligated to volunteer and if I did so then they would take me as an officer in a position. So, it wasn’t too hard of choice at that point. I became an Obligatory Volunteer and the Army cashed in on it when I had a few months to finish in my training. So in 1971, Marsha and I and Debby and, by that time, Karen and Steven were both born, all three of my kids were already born, packed up and moved to San Antonio, Texas for about five months. That was the Army Medical Field Service School at Ft. Sam Houston, in Texas, and so we lived there for a few months and while we were there, this was 1971, and this war had to end. President Nixon promised he would end it and it was just going on and on, so we figured anything I could do to stay in San Antonio might prolong my having to go away and so I got enrolled in a program that was called Preventative Medicine and Public Health which actually matched my Fellowship and got to stay a few extra months, but sooner or later my number came up and Marsha moved back to Columbus and I moved to a place called Da Nang in Viet Nam and that’s a whole other set of stories I can talk about a little bit, if you like, but the hardest part of that whole thing was the year that we were separated. Marsha was raising children who were four, two, and one-half to one, it was very difficult for her and we did not have cell phones and we did not have the availability of communications as we do today and once a month I was allowed to make a phone call through what was called a Red Cross Phone and for $35 you could talk for ten minutes and the first five minutes were usually “I can’t hear you. Speak louder.” and you didn’t realize how short ten minutes could be until that’s all you got per month and then when you were lucky you could also go on the amateur radio system. It was called the Mars System, the Military Amateur Radio System and you could call home and you’d have one of those conversations like you were on a car radio or airplane radio. You know, “How are you today, over.” “Everything’s just fine, over.” It was one-way communications and somebody had to push a button in between, so that’s how we kept in contact and letters and tapes that I would send home, and tapes and things she would send to me.

INTERVIEWER: You were there how long?

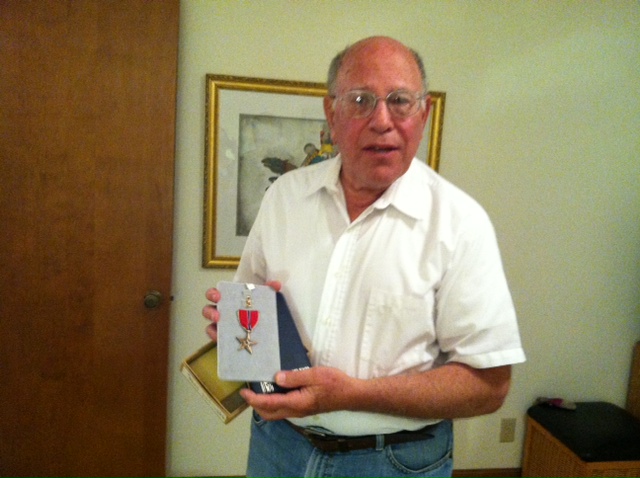

POLSTER: I was there a year, a little short of a year. If you want to know it was exactly 11 months, 12 days, 22 hours and 14 minutes. That’s how long I was there and for me it was kind of like going to Boy Scout Camp or whatever with occasional sudden danger. For her it was a nightmare because she never knew. Every time she would pick up a paper and it was say such and such happened two miles from where I lived she would have to wait a week to see if my next letter came and it was very, very difficult for her, but I’d like to mention, can I mention a couple things about that experience, Jewishly?

INTERVIEWER: Yes, please.

POLSTER: The Jewish experience in Viet Nam was very interesting. There were about three hundred – well, maybe that’s too many – maybe two hundred Jewish soldiers in the area that I was in called

I Corps in the northern part of South Viet Nam at the time. And most of them, they were either officers like myself, or physicians or dentists or lawyers or people of that sort, occasional career officers or most of them were 18 year olds and coming from Columbus, Ohio, where almost everybody seemed to have a middle class family, almost everyone seemed to come out of either business or professions, for the first time I was coming in contact with Jewish soldiers whose parents might be garbage collectors, or might have been tailors or might have been other things from New York, and in Chicago and Los Angeles, and instead of going to college they’d been pulled in or decided to go into the Army or the Marines. It was really an eye-opener to see who came to Jewish services and so forth. I was already, let’s see, in 1971, I was already 29 years old so I was really an old guy compared to these 18 year olds who were the soldiers who were fighting and we had three rabbis in Viet Nam at the time. There was one for each of three areas, north, the center and the south, and it so happened that we had three Reform rabbis, just by coincidence, at the time of Passover. I arrived on April the first in 1971 and Passover was on April the 9th in 1971 so this is a little story I’d like to share with the Historical Society. I went to meet the commanding officer at a hospital to which I was assigned and he was a full colonel, a fairly high ranking person in charge of this hospital and he was Jewish and I was shocked and he called me in to his office and he said to me two things. First of all “My surgeons can operate on Vietnamese, my internal medicine doctors can treat their illnesses, but you’re a pediatrician and if word gets out that you’re treating children in my military hospital, I won’t get my promotion to General.” So, he sent me to what we called the emergency room. That was the first thing I wanted to say about it. The second thing he says, “Oh, by the way, Passover’s in eight days. Would you like to fly in my helicopter down to where we’re having services?” I said “Sure, this sounds really nice.” And there wasn’t anybody else Jewish around where I was and so there was just the two of us. So, on the given day I get in his helicopter and we fly down to a place called Chu Lai for seder and there were about two hundred people gathering for this seder and we go in and a couple of interesting things. There were some Vietnamese Generals that were invited to sit on the sort of the head table or dais and they each had a yarmulke on their head with their appropriate rank, One or Two or Three-Star General. It was kind of cute and everybody sort of snickered and laughed about it but the other thing that was actually most memorable was it came time for The Four Questions and they went around the room of two hundred people and to determine who was the youngest it was the person who had most recently arrived in Viet Nam and that was me. So, they asked me to stand up and say The Four Questions and when I did there were tears in the eyes of many of the men that were around me and I was really kind of puzzled. Why are they crying? And they knew that they all got to go home before I did and for some it was a very emotional moment, but that’s my memory of my Passover seder in Viet Nam.

The other thing that I’d like to share is that it seems that some stock and trade is really worth a whole lot more than you think it’s going to be and it turned out that a mistake had been made and instead of ordering 30 cases of Lipschutz Malaga Wine, the mess sergeant had received three hundred cases and the rabbis who were in charge of this religious wine then passed it out as favors to many of the Jewish officers so they in turn could trade it for things and I know of one fellow who traded ten cases of Malaga Wine for a Jeep. Another one got four or five room air conditioners for his cases and so forth. So, this terrible wine that I would not recommend to anyone was sweeter than syrup. It became a very good stock and trade and it seems that some people who really liked to drink a lot didn’t care what they were drinking. So, it became a very interesting thing that the rabbis had this commodity that nobody wanted among the Jewish soldiers but that was very popular as something to trade. We also had, and I’ll just mention one other thing, and we can go on to other topics. We called a Passover Retreat, a Passover Retreat in a place called Cam Ranh Bay. Cam Ranh Bay was kind of like going to the beach in Florida or maybe the Texas Coast or maybe Southern California beaches, wide expansive beach, clean, nice, resort looking place. The fact that a war was going on seemed very distant from Cam Ranh Bay. The rabbis at that time had changed from three Reform rabbis to three Orthodox rabbis in three parts of the country and somehow they convinced General Westmoreland, who was in charge of all the activities, and General Alexander Haig who was the actual General in charge, that Hanukah was the most important religious holiday of the year for Jewish soldiers and, as such, every Jewish soldier had to report, had to remove themselves from the field where fighting was going on and had to report for an eight day Retreat to Cam Rahn Bay. So, we had about five hundred soldiers at Cam Rahn Bay for a week. We had this wonderful program where we studied Torah by the sea and the whole object was to get people out of harm’s way for as much as they could. Another little trick that the Jewish chaplains would use is they would appoint very vulnerable young soldiers to be their accompaniment or their guard when they would travel from Viet Nam to Hong Kong to get the kosher food. That was the nearest source of kosher food and so these people would have to leave their battle units and have to go with the rabbi to go pick up the meat and they’d have to spend four or five days in Hong Kong before they would come back and have to go back to war again. So, the rabbis seemed to everything they could to keep Jewish souls alive. So, those are just some of my Viet Nam recollections about being Jewish. Oh, one last thing I want to mention is that every Friday night in the Northern part, in Da Nang, we had a Friday evening service at the Air Force Base in Da Nang which was about five miles from where I was stationed. So, I would drive over and I would have an armed escort who would drive my Jeep and take me over to services and there were ten or 15 of us who gathered every Friday night and I remember two things. One, there was a package that arrived for all of us and inside the package were these little bags of various items, razor, and soap and some other things and a little note that was in my bag that said “Hand-packed With Love by Sadie Schwartz of Newton, Massachusetts Hadassah” and you know, I still have that bag to this day and it was just a very touching thing. The other thing that I want to mention is that one of our members, one of our regulars was an Air Force pilot who ultimately was shot down in his plane over North Viet Nam and was a Prisoner of War and returned when the Prisoners of War returned, but we all knew the night he didn’t show up that that was bad news and so it was a very difficult moment. So, those are some recollections.

INTERVIEWER: How did you learn that you were coming home?

POLSTER: Actually my work for the last six or seven months in Viet Nam was in the area of trying to deal with drug abuse. I had set up programs to identify and treat soldiers who were abusing drugs. There were some problems. If you put a soldier on an airplane for 14 hours and he was addicted to heroin, in the middle of the flight he would have a medical crisis and it really disrupted things to have people writhing on the floor of an airplane and screaming and yelling. So we had to set up a program to find people before they got on the airplanes and I was in charge of developing that and I worked at that for six or seven months and we had a program we called Operation Golden Stream where before you could get on the airplane you had to have your urine tested and if your urine was clear you got on the plane, and I don’t remember exactly how I positioned myself to leave the country, but I was ready to go and it was a little before my time was going to be up, but I had arranged with some people in personnel section to get me on the manifest, as they say. So, it was February and I was repositioned from Da Nang to the Air Force Base in Saigon, outside Saigon, a place called Long Binh. We were hanging out there for a few days trying to get on an airplane to get out and I was one of the soldiers who got pulled up on Operation Golden Stream but luckily my urine passed but it was my employees if you will, my soldiers who were doing the test so my test came back negative before the urine ever left the bathroom, but it was an interesting moment and a very exciting moment. I was very glad to leave when I did because the War was continuing to go on and it was not getting any fun so, it was good to get home.

INTERVIEWER: What was the homecoming like?

POLSTER: Homecoming was, I did not have the homecoming that we all hear about where people said nasty things or spit on you or wonder why you were a soldier or whatever. I just got off a plane in McCord Air Force Base, which is in Washington, took another plane to Columbus, got home at about 6 o’clock in the morning, took a taxi to my house in Bexley, and I still remember the sight of my then four year-old and two year-old girls jumping up and down in the window of that house which had windows all the way down to the bottom, to see them jumping up and down, “Daddy’s home! Daddy’s home!” and that was my homecoming. Adjusting was not a big problem. I can honestly say that it was really very easy to adjust because I had to go back and immediately finish my last four months of Fellowship. So, I was home for, I think, two days and then I was back at Children’s Hospital and finished my program there, but it was really a very interesting time of my life I must say, and one that I’m very saddened that I missed that year of my children’s growing up.

INTERVIEWER: Did, I just forgot what I was going to ask…[!]

POLSTER: Well, I can tell you that, for a while, my politics changed quite a bit through this experience, I must say, and whereas I may have gone over to war, if you will, with a little bit of a conservative outlook of war was probably a just thing, it was probably the right thing to do, certainly for me whether the War was right or wrong, the soldiers needed to be treated and I was in the medical field and I needed to make sure that everybody that could got home safely, so I always felt it was a special role for me, but it didn’t take me more than a few days to begin realizing the waste, how terrible war is in general and how terrible this war was and the decisions that we made to go there. So, my politics really turned around, so by the time I came home I thought everybody else should be with me and come home. When I saw all the materiel rusting and rotting on the deck of the wharfs and the military industrial complex – they were all making lots of money, you know, American lives were paying for it, but I guess that’s the story of every war. Also, I had some really very bad feelings. I remember for a while I had a hard time when I’d go to some sporting event or whatever, I just had a hard time singing the Star Spangled Banner for a year or two. I just felt that somehow I couldn’t do that as long as the War was still going on. I still stood up when I saw the flag and I was very respectful and I never really discussed it much at the time but, you know, we all had choices in those days. I could have gone to Canada and made a life there or done something else but I chose to serve because I thought it was my patriotic duty. I still feel that each of us owes our country whatever we can give to it, for the blessings that we have even as dysfunctional as we can be sometimes, we still have the best place on earth…

INTERVIEWER: Did you keep in touch with any of the people with whom you served?

POLSTER: No, I was a commander so I had people that were commanded by me. One of the things I did for a few months was that I had what you might call today an Urgent Care or a Dispensary Unit, a clinic. I was the physician but I had corpsmen and ambulance drivers and I had some other people who worked for me so in that capacity as an officer I had to meet out discipline, worry about the guy’s girlfriend who wrote him a letter, “You’re not my boyfriend anymore.” I had to deal with that. So those were not people that I would probably have stayed in touch with. There were a couple people that I knew from here, actually, that I saw there, other physicians. Well, Joe Schlonsky was there when I was there. There was a fellow by the name of Harlan Pollock who was from the Columbus community. From Texas there’s a plastic surgeon and he was there the same time I was. There were some others like that, but many years later I got a call from a guy who was an ambulance driver and he was from Columbus, actually. There were two people from Ohio in this little unit and he was trouble. I had had to punish him. Punishments – that’s when it was usually financial, you now, take a hundred dollars of your pay or something like that for getting drunk and driving the ambulance and things like that – and I always worried that some of these guys might look me up someday and I get a phone call one time from Dawkins and Dawkins says, “Doc, I need a favor.” And I think what is going on? My kid’s gotta’ go to preschool. Could you fill out a form?” And I felt, okay this one’s okay and actually he brought his child in and I saw him and that’s the last time I saw anybody from that unit and I really haven’t kept in touch with any of the people. There was one fellow that I went, from Ohio State, we were on the same plane, in the same unit, in preventive medicine, we spent our year there, came back on the same plane back and I saw him one time since then, another doctor. He lives in South Carolina, but he trained here at Ohio State. So, I haven’t been in touch.

INTERVIEWER: Marsha, I assume she did not keep teaching while you were gone.

POLSTER: No, she stopped teaching in, she went back after Debby was born but by 1969 I think she stopped and then I think she didn’t go back until Steven was six years old so she was at home by then.

INTERVIEWER: So when did she start the school?

POLSTER: Oh, the preschool at Agudas Achim? Well, for this interview my wife was sitting at the Jewish Center swimming pool, not in the Jewish Community Center in those days, just the Jewish Center and a friend came up to her and said “I understand you’re a teacher” and she said “Well, yes I used to teach first grade, second grade and some kindergarten experience.”

“Well, we’re looking for a director and teacher of a new preschool at Agudas Achim” and at that time Steven was five and he was going into kindergarten and she said “Well, I don’t really have the time. I want to volunteer in the kindergarten. He’s my baby. I have a chance to get in the schools now and do these things but keep me in mind.” Well, we need somebody to help develop the school and we aren’t going to open in until next year.” So, they persuaded her to do that and she did that for 25 years, and had a really wonderful school, I think, until it closed in 2000 and at that time she decided she was also done as an administrator and would be happy in her new career just as a teacher or as a specialist and so that’s how she became a Judaics Specialist at the Jewish Community Center and a Sunday School teacher as well. Sunday School teacher’s only been the last 13 years or so.

INTERVIEWER: So, personally I’m going to just throw this out. I have noticed something that I think is really beautiful, is that you are very supportive of her and every time she has a program, because she and I work together, you are always there, you always come up to her afterwards and greet her and, I just, I mean, that’s a really wonderful thing you do. So, do you have any comment to make about that?

POLSTER: Well, our lives are intertwined and we both work with kids, in different ways, but it makes me so proud to be Mrs. Polster’s husband. She really is in this community a more important person than I am, in my eyes anyway, and has been. When she had the Preschool at Agudas Achim she had a number of children during that 25 year period that grew up and among her last students there, there was a student of an academic from the Melton Center at Ohio State. His daughter was graduating from Torah Academy or maybe it was an 8th grade graduation. I think it was an 8th grade graduation from Torah Academy and we went to the ceremony because four or five of the kids graduating had been in her preschool all those years earlier and when this noted scholar came up to her and began to talk to her about how important she was in his daughter’s life, I just melted. That to me is the most impressive thing to hear and I’m just happy to be connected in some strange, distant way with that and so I’m very pleased with everything that she does and I want to be a part of it. I don’t want to miss it and also, we made a little deal. We separated for a year and we’re together for the rest of life. There may be a few days here or there where one of us is gone, but she’s always been involved in everything I’ve done certainly. I want to be with her as much as I can.

INTERVIEWER: And you have grandchildren. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

POLSTER: Well, I have eight grandchildren. First of all let me talk a little bit about my kids.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, yes, thank you!

POLSTER: …because they are the next generation and if you teach your children to be free thinkers and world travelers, that’s exactly what they will become and mine did and all of my children have had fortunate events as a result of travel, one way or another, as a result of experiencing the broader aspects of life. My oldest daughter whose name is Debby Polster Appelfeld went to the University of Wisconsin after, and I should say she went to the University of Wisconsin because she had gone to Camp Ramah for five years and that’s just an extension of Ramah for those kids in Wisconsin and she went to Wisconsin where she was not particularly involved in Hillel and those sorts of things but she always maintained her relationship with her former Ramah friends. After college she went in to the field of community service first in that she was involved with fundraising activities for first political action groups, and after that fundraising for museums and aquariums and those sorts of things, married, had a child, at that time was living in Charlotte and when her husband needed to find a new job and went to a head hunter and said, “I need a Fortune 500 company,” and the guy said “Well, I have this job in Columbus, Ohio,” and brought Debby back to us so we are fortunate to have one of our children here, but the reason I say that it’s important that they be involved in Jewish life and they were, Camp Ramah took her to Israel after many years of camp. Israel attracted her enough so that she wanted to go and study there again in college and while a student at Tel Aviv University she met her future husband who was also doing a semester abroad. He was from Maryland and so that worked out really well.

Our second daughter [Karen] who did not go to Wisconsin, but went to the University of Kansas, found her relationships with a few Ramah friends are what kept her emotionally stable and kept her going at the University of Kansas in her early days when she was really on shaky grounds as an early freshman and not knowing anyone else, being away from home and so forth and had also been a Camp Ramah person and had also gone to Israel with Camp Ramah. So, she was able to live in another community in which she still lives and she has three children. Two of her children attend Jewish Day School. The third in public school will have a bar mitzvah next May. Her husband is a convert to Judaism who converted before they married because he thought it was the nicest religion he’d come across, so it was nice to have that happen. It was not just a condition of marriage but actually it was very interesting. I went to the mikvah with him but so did his father who was happy he was just going to have some religion. His father was a very religious person, not Jewish, and was happy that his son was finally going to believe in something. Matt has been a very active and committed member in Kansas City along with Karen.

Then my son, who also went to Camp Ramah and was president of USY, by the way helped coin the term “BUCKUSY” – that was what they did in his year. My daughter Debby was also president of the local USY chapter. Karen was a first vice-president so all of them were involved with that as well as Hebrew High School and Ramah. Steven lives in California where he belongs to a congregation. His kids have gone to Jewish Preschool. He’s involved in a chavurah from his synagogue, so, he’s got a Jewish life as well.

So, that all of my children have passed on to their children the importance of all this, so I find myself very fortunate. You asked about my grandchildren. As I said, Jewish preschools, Jewish Day School, people going to have bar and bat mitzvahs. My oldest grand-daughter, who lives in Columbus, is starting to get involved in some other things. She will soon be attending a high school program at AIPAC, the American-Israel lobby next month in Washington as one of the high school representatives so she’s sort of representing the next generation in some of these activities. She’s also a Camp Ramah kid, the second generation of that and I have no doubts that, at least in our family, there will still be Jewish people for a while. So, it’s really wonderful. I would love to live vicariously through my grandchildren. As they get a little older they begin able to not only parrot and mimic, but also act and think for themselves, it gets really exciting to see how wonderful they are.

INTERVIEWER: So, talk a little bit about technology. So now you can Skype with them and all kinds of things.

POLSTER: Yea, we Skype, or face-time, talk on the phone.

INTERVIEWER: It’s very different from when you grew up.

POLSTER: Very different. It’s a different world. It’s interesting for all of us. My grandchildren text me so I have to learn some new skills, learn all these little smiley faces and those sorts of things, so it’s been interesting.

INTERVIEWER: Go back for a minute. How did you get in to practice?

POLSTER: Oh, first of all, when I was still, after Viet Nam, to take a step back, my wife and I and family returned to Ft. Carson, Colorado, which is in Colorado Springs. That was my reward after the punishment so, we got to live in Colorado which is, you know, close to heaven. It’s beautiful, for a year. I was in a part of nine pediatrician group at Ft. Carson and theses nine pediatricians came from a cross-section of the United States. One had trained at Harvard. One had trained at UCLA and so forth and we were just a cross-section everywhere and one of the fellows had the medical practice opportunity in Denver and said “Why don’t you stay here in Denver. There’ll be three of us. We’ll join this practice. There’ll be six altogether when we’re done doing that and we’ll all about the same age and experience and we’ll have it for a good long while.” And it was very tempting to do that, but I thought about it and decided to move back to Columbus to be closer to my parents who by that time were getting older and it really felt important to have the family connection. So we came back to Columbus, I finished my Fellowship and decided to open a private practice by myself. So, I basically hung out a shingle, if you will, or opened an office. I supported myself by covering every other practice on the east side of Columbus while people went on vacation and working for them trying to earn a little income while getting my own practice ready and started practice in 1973 with a receptionist and a nurse and myself and I was alone for six and half years. Then one of my fellow trainees from Children’s Hospital by the name of Alex Dubin, decided to relocate from Toledo and he talked to me and I said “Why don’t you join my practice?” which he did and the two of us then practiced together as a two-person practice really until 1991, so we were together for a good long while. The practice has now grown. There are currently six doctors in the practice.

INTERVIEWER: Are you there full time still?

POLSTER: I’m not full time in the same sense that I was. I see patients four days a week. I then spend the equivalent of another day and a half a week running the administration of the practice. That means making lots of decisions, paying the bills and doing all those sorts of things and really in today’s world it takes a lot of doing. There’s a lot to be done and so I put in about 5 and a half days now I guess. I still take call and rotation when my partners are on vacations and weekends and things.

INTERVIEWER: But to your kids and your grandkids you’re “Dad” and you’re “Grandpa.”

POLSTER: Oh, yea. None of my kids have ever directly come to me for medical advice because they know better. I’ve always made sure they had their own doctor and it was not necessarily in my own practice. When they’ve moved on out to different places and my daughter Debby moved back to Columbus and she decided that my partners would be her doctors but never me and has probably never asked more than one or two medically oriented questions ever of me. She really knows how to separate that. My other two kids have called about a lot of things, but it’s usually to confirm or verify what their pediatricians have already told them and they’ve been fortunate in finding people that have a similar philosophy to mine so I’ve never had anything to argue about with what their doctor has wanted to do. So they know what I am and what I can do and occasionally something humorous comes up out of it. I remember my son one time asking me to look at a rash that his daughter had and he happened to be living in Rome, Italy at the time and I was here and he wanted to put it on Skype and the rash was in a place you don’t show on a computer and I said, “No, just describe it to me. It’s alright. I don’t need to see it and have it on my computer,” and so those humorous things have come up but we’ve been really fortunate. None of my kids had the desire or inclination to become physicians. They are all happy with what they do.

INTERVIEWER: Something that comes up all the time is people say that maybe not right now but there was a time when everyone Jewish in Columbus was related. So, they were talking about the Polsters and Schlezingers and the Rubens and …do you have any comment about that?

POLSTER: Well, I think you have to be very careful about what you say in any mixed group because you’re probably talking to somebody’s cousin. I mean, this was a relatively small Jewish community for a long time and part of its growth was just the growth of the individual families, but also a lot of these people in two generations ago knew each other before they came here. So, they had inter-relationships that went way back so there is a lot of that but in fact, when you go around a room these days for me to say that I’m a native of Columbus and Bexley, I’m usually in the vast minority of any Jewish group right now, even though I have all these family connections. It’s shocking to find two or three other people who really grew up here from infancy. We’ve given mobility to our children so our children and our grandchildren have moved out into the whole community. It’s interesting in that respect and it has been a small Jewish community but when you’re active in it you do get to meet a lot in the cross-section.

You didn’t really ask about other things I’ve been involved with in the community and I’d like to mention them as part of this interview because I have served on many boards. I was on the Federation Board I don’t know how many years but I was head of a couple of different budget committees. I was the head of the Education and Culture Committee for several years. In the early 2000’s when they asked me to come back “Please would you do it again?” So I had a lot of Federation involvement from the 1970’s to the 2000’s, not that much in the last ten years. Back away from that a little bit I was on the board of Heritage House for good number of years maybe ten altogether. I was on the board of the Jewish Center. I was a chairman of something called the Hoover Development Committee at the Columbus Jewish Community Center, which you probably have never heard about, but the campsite that’s at Hoover – some years ago we obtained a donation, a good sizable donation from an individual whose last name was Berman to put to use just for that Westerville campsite on the water and someday build a retreat center and someday build cabins and whatever else might be needed and while that has never happened we have done repairs to the swimming pools. We’ve done repairs to the shelter house and those sorts of things and the Center still comes to us and asks for uses for money from these funds. It was a formal committee for many years and I’m still, I guess, one of the trustees of that fund. It hasn’t had a lot of activity but we still have some interest in what can be developed because it’s a beautiful part of the Jewish Community Center. It really has become the alternate summer location with the swimming pool and activities and the camp and so forth. I have been involved with some other Jewish-related organizations as well as community organizations: March of Dimes, the Columbus Medical Association – I’ve been a member of its’ if you will Ethics Committee, or Public Relations or what is called, “Physician Relations Committee,” for doctors who’ve done some things that the others aren’t so proud of, they come to us and we try to decide whether or not it’s worthy of pursuit or whether or not someone needs to have a correction in their ways or if they’re just fine. I’ve done that for almost 30 years now. So, I’ve been involved with that and there are other pediatric societies. There’s something called the Central Ohio Pediatric Society that I’ve been involved with. So these are all some of the community activities along with Bexley kinds of things. We’ve served in different roles in the schools and been supportive of the Foundation, and the Bexley Community Foundation now and those sorts of things as well. Bexley has been a very important place for me and my family particularly. My grandfather came here in 1920 so that makes us one of the oldest residents, I guess. By the way one of those houses was a Schlezinger house, too.

INTERVIEWER: That was another one of the families…

POLSTER: So, those are some of the general activities we’ve had. There was a time when I traveled a little bit to give some lectures on medicine and on community health issues, that sort of thing. That was kind of fun.

INTERVIEWER: So, if you had to say what your philosophy of life is.

POLSTER: Philosophy of life… I don’t know how to put it in to words but you need to appreciate what we’ve got and we need to leave the world a little better place than what we found it in any way we can do that if just as simple as a smile to someone who needs a smile or to do some good for people to help them out in some ways, to be generous when we need to. Actually we need little sets of rules when we need to try to live a life that we’re proud of and that others will recognize that we contributed to. I think that’s important. My dream is that my children will grow up to be more generous than I could ever have been and you know they are. My son, he can’t pass a panhandler on the street without putting something in the hat. So, I guess it’s in all of us a little bit. I just hope that it continues. I have a very exciting family. We love to get together. We all look forward to that. We don’t have any black sheep so to speak that I know of and if I’m the one that’s the problem they don’t tell me. So, I think that I’ve just been really fortunate. I grew up spoiled. My mother took care of me. I was a good mama’s boy. That’s a nice story. When I went off to college, every Tuesday I would take my dirty laundry to a depot where a truck was going to be coming, and my brother-in-law was in the trucking business in those days. It would pick up my dirty laundry on Tuesday and I’d go back out on Thursday and the duffel bag would be there and the laundry would all be washed and folded and usually a box of cookies or something like that on top and my mother did my laundry the whole first year that I was in college. Talk about being spoiled. So the money that they gave me for laundry I used to put in the pinball machines for any of you that might remember pinball machines. They used to cost a nickel. So, I lived a very privileged life as far as I was concerned.

INTERVIEWER: It was pretty loving and then you turned around and paid it forward. I don’t know if it’s so spoiled or just loved.

POLSTER: I’ve always felt that we need to take care of ourselves first, family first, the Jewish people first, but not exclusively. That’s why I’ve always tried to find things that I could be involved with that are outside of that as well, to help my community, the place where I live, to make it all a little bit better, but my wife and I love to travel. We have traveled many, many places and we’ve been fortunate to be able to do that. We have learned so much about others in the world through that travel and other places, other ideas, other customs. It’s always fun to travel because I am sort of a political person in terms of following politics and I just love to discuss with Israelis or Europeans or Asians U.S. politics and European politics, whatever just to get their opinions. One of the things I’m impressed with is that we’re really pretty highly respected by most people still. This is thought of as a successful country and I’m just happy to have been one person who in it who’s done some things that may have helped, and certainly I am not innocent of any mistakes. We all make mistakes. We all have regrets in life, things we shoulda’- woulda’- coulda’ but it has just been a blessed life. I have nothing really to complain about.

INTERVIEWER: Where were some of the places that you traveled?

POLSTER: Well, aside from my free trips to Southeast Asia by Uncle Sam, we’ve mostly traveled Europe, a little bit of South America, all of the U.S. I pride myself in having slept overnight in 48 of the 50 states. I’ve been to all 50 of them and when our kids were little we did lots of camping where we would take tents and pitch a tent and we’d sort of outgrown that and over the years we used to go skiing on ski trips and that was very enjoyable. Wintertime usually takes us to some beach somewhere, somewhere where it’s warmer so we can get out of the weather. In the summer we took a trip to Scandinavia where we spent a week just traveling through Norway and Denmark before taking a cruise and one of the fun things to do of course, is Jewish travel. When you do that you try to find the little synagogue and see what’s going on and sometimes you know more than the people think you do. We were in Rome, Italy where our son lived for five years. When we were there just at this time of the year several years ago and it was Hoshana Rabba and we wanted to go in to the central synagogue. There’s only one major synagogue in the city or Rome and five congregations use it and it’s right on the Tiber River and it’s very close at the edge of the ghetto and so we went over to visit the synagogue and there was a guard standing outside. We didn’t know he was a guard He looked like one of the Israelis with the close cropped haircut and the t-shirt and the pants with the little bulge on the side where his weapon was and he said, “The synagogue is closed for a Jewish holiday,” and my wife said, “This is Hoshana Raba. It is not Yom Tov. You can’t tell me that it’s closed today.” He said, “Well, I have to tell you that this one of the biggest tourist attractions in Rome and it was Hoshana Raba and they just knocked all the leaves off of all the willow branches and we have to clean up.” So, that was the true story, so, we got to go back another time to visit. It’s been interesting. We were in Athens, Greece and we visited the synagogue there, in Hungary, synagogue there. Florence, Italy, they had a famous flood in Florence and the waters rose to about three feet up to the ark doors and you could still see the water marks. On this last trip we saw Holocaust memorials in Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and a big one in Berlin, Germany, and there was also a Jewish presence in St. Petersburg and we got to visit the synagogue there and so forth. So, that’s the kind of thing we like.

INTERVIEWER: Israel?

POLSTER: Been to Israel six times maybe. I’ve lost track. My first trip to Israel I was a 17 year old who went on a USY pilgrimage in 1959. Israel was 11 years old then. I have pictures from it, but it was a really exciting trip. I met some friends there that I kept in touch with for a while, for a long while that I’ve lost track of now. That was my first trip. Then we were there in 1979. We went with the Columbus Jewish Federation – had a leadership trip and Marsha and I, not Marsha, but certainly I was the old guy. I think there was one other person on the trip who was my age. Everyone else was younger and since then every one of those people that I can think of has taken major leadership roles in their community, Federation and their synagogues and everything else. Just this last set of Holidays I was sitting in synagogue services and there were a row of us that were on that ‘79 trip. We just all looked down the row and we were back in those days. We’ve taken several trips since then. We’ve have gone to two CAJE conferences in Israel, CAJE being the Coalition for Advancement in Jewish Education. We loved that. I used to go to those CAJE conferences and what I used to enjoy the educational aspect of it was so wonderful. So, I think if you ask what have been the pillars of my life aside from my own family, it’s been synagogue, my kids and now grandchildren getting so much out of Jewish camping, my kids having continued their Jewish life and my grandchildren now picking up a Jewish life. My father taught me that you can’t get mad at a building. You can only get mad at the people that run the institution so you should belong to everything that there is in Columbus that’s Jewish. Now I don’t belong to every synagogue in Columbus but his message was, you join the Jewish Community Center because Columbus needs one whether you go there or not. You support the Jewish Family Services whether you’ve got a job or not. You take care of the Heritage House whether you ever need it or not because without that you’re not really taking care of your community and so, I want to pass that on to others. I want people to feel the same way about supporting our institutions and if it’s not right, instead of getting mad, make it better. That’s what we have to do. And now I’m a proud member of the Jewish Historical Society as well.

INTERVIEWER: Well, this is more than I even, this is just remarkable.