A History of the Jewish Community of Lancaster and the Surrounding Area

by Austin Reid

Exterior of Congregation B’nai Israel ca. 1993

Courtesy The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette

Acknowledgments

Two individuals provided invaluable contributions to this work, and additionally graciously offered both their encouragement and advice as I undertook this research. Therefore, it is proper, and a pleasure, to recognize them both for their assistance in making this paper a reality. Given that each individual gave such valuable aid, I have elected to recognize them by alphabetical order. The first person I would like to thank is Dr. Pantsov, who contributed to this project as my Program Advisor during my final year as an undergraduate student within the History Department at Capital University. Specifically, these contributions included providing support from the onset of this project and serving as the primary editor of this work. It should be noted, however, that any errors in this final version of this piece are solely the fault of the author. The second individual who deserves ample thanks is Toby Brief, who, at the time of this composition, serves as Curator of the Columbus Jewish Historical Society (CJHS). Without this crucial institutional backing, subsequent access to the CJHS archives, and advice on how to organize my research, this work would not have been possible. Additionally, I would also like to thank Mary Lawrence of the Fairfield Heritage Association for her interest in and support of this work. A special thank you also goes to Alan Shatz, who took the time to be interviewed for this project. Finally, I would also like to thank my great-grandparents, Dorothy and Russell Moore, who served during World War II and who counted several Jewish people in Lancaster as their friends, for providing the initial inspiration for this work. May their commitment to civic engagement and tolerance continue to be sources of inspiration for years to come.

Austin Reid: Columbus, 2017

Introduction

Lancaster Ohio as it is known today has a rich history dating back to the year 1800, when German settlers from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania came together to establish the village of New Lancaster. By 1805, the town had shortened its name to Lancaster, and in 1834 the newly opened Lancaster Lateral Canal helped to set in motion the rapid growth of the new city.[1] Over the next several decades many different ethnic and religious groups settled here including Irish Catholics, English Episcopalians, and Presbyterian Scots. Another group was European Ashkenazi Jews. The first Jews in Lancaster hailed from German-speaking regions in Central Europe, but by the turn of the 20th century Jews from Eastern Europe also began to arrive in the city. The Jewish population, while small, nonetheless managed to contribute to the overall growth and development of Lancaster. Much of the history of this community has gone unpublicized, however, and, with the closing of Lancaster’s historic synagogue B’nai Israel in 1993, this element of Lancaster’s history risks being forgotten. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide a historical overview of Lancaster’s Jewish community and highlight Jewish families who lived nearby in smaller towns. This paper also seeks to demonstrate how Jews and non-Jews interacted in Lancaster, how Lancaster’s Jews were impacted by their coreligionists in other parts of Ohio, and how Jews made measurable contributions to the region as a whole. By understanding the history and impact of Jews in Lancaster, and surrounding areas, one can be given a better appreciation for the diversity of peoples who shaped Lancaster into its current form and of Jewish religious life in an American small town.

Itinerant Traders: Lancaster’s Earliest Jews

A traveling peddler known by the name of Frank was among the first Jews to stop in Lancaster regularly for business. On September 29, 1853, The Weekly Lancaster Gazette ran an advertisement in its “Local Intelligence” section which references Frank and his services, and it is this publication that published the earliest reference explicitly mentioning the presence of a Jew in Lancaster. Frank’s advertisement utilized a memorable play on words by stating, “Frank, the wandering Jew, who makes everybody [sic] ‘wander’ how he manages to sell at such low prices, is prepared to meet the wants of his customers. His stock can’t be surpassed. Give him a lift”.[2]

Frank, like many American Jews of his era, was engaged in the peddler’s trade, and, through his travels, he helped to serve as a vital link between various small towns and larger urban centers. It is likely that Frank was among the 250,000 German-speaking Jews to immigrate to the United States between 1820 and 1890.[3] Many of these Jewish immigrants became peddlers after arriving in the United States, and the most successful went on to establish more permanent businesses in towns across the country. In addition to Frank, other Jewish merchants visited Lancaster by the late 1850s. A few individuals, including Adolph Aaron and Isaac Levy, remained to open stores. Adolph, an immigrant from modern-day Germany, sold clothing and jewelry at his shop on Main Street from around 1859 to 1863. Isaac Levy operated a clothing store out of the Shaeffer Block on Main Street by 1856. A business partner and likely relative, Moses Levy arrived in 1856. Moses, who was an immigrant from Alsace, raised seven children alongside his wife, Pauline. By 1878, the family relocated to St Louis, Missouri. Another immigrant, Jacob Block also joined the Levy clothing business in 1856. He remained in Lancaster until 1865.

The presence of Jews in Lancaster’s local business scene can also be seen through anti-Jewish references found published in certain local advertisements. For example, a jewelry company known as Gates & Cosper repeatedly ran an advertisement in 1850 stating that their watches were “an honest class of jewelry instead of a Jew article”.[4] Additionally, a clothing store named Smith & Tong openly advertised during the same year that its stock is “not purchased from or manufactured by Jews”.[5] Such advertisements indicate that, while anti-Jewish attitudes were present in Lancaster during this time period, Jewish businessmen were able to compete effectively with their non-Jewish counterparts to such an extent that they were singled out in advertising.

Establishing Roots: Lancaster’s Earliest Jewish Families and Their Economic Contributions

While Jewish businessmen were active in Lancaster since at least the 1850s, it was not until the turn of the 20th century that records indicate that several Jewish families began to reside in the city at once. Two of the earliest families known to have lived in Lancaster were the Altfaters and Molars. David Altfater, the patriarch of the Altfater family, arrived in Lancaster with his wife Lena around 1900, and by 1914 he had set up a scrap metal shop out of his home on East Chestnut Street.[7] This business later moved into a larger retail space and became known as Lancaster Iron and Metal Company. A few years later in 1907, Morris Molar also arrived in Lancaster from Philadelphia with his wife Rachel and their oldest child Hilda. By 1913, he also established a scrap metal business in the city, which was named Molar and Son Fairfield Junk Company.

Both David and Morris were among the over two million European Jews to arrive in the United States between 1880 and 1924, and it is from this same immigration wave that a majority of Jewish families who resided in Lancaster drew their roots. David Altfater was a native of Austro-Hungary, and accompanying him and his wife on their journey to America where his two oldest daughters, Rachel and Rose. The Altfaters were preceded by Jacob Moskowitz, the brother of Lena Altfater, who arrived in America with his wife Rachel around 1885. It is not known when the Moskowitzs arrived in Lancaster, but once established in the city Jacob opened a saloon known as The Buffalo, which was located on Locust Street.[8] Jacob Moskowitz does appear in 1900 United States Federal Census, which indicates that he and the Altfaters lived in the same household. No reference to Rachel is found in this census record, however, and it is known that Jacob never had any children.[9] While it is not known specifically where Morris Molar was born, census records do indicate that it was somewhere in the Russian Empire. His wife Rachel, however, is known to have been a native of Kiev.[10] Morris and Rachel wed after their arrival in the United States, but before relocating from Pennsylvania to Lancaster. After the initial arrival of the Altfaters and the Molars several other Jewish families settled in Lancaster, and the surrounding vicinity, within the first and second decades of the 20th century. By 1920, the federal census recorded twenty adults in the city who listed their mother tongue as Yiddish, a language commonly spoken by Jews in Central and Eastern Europe.[11]

As was the case in many contemporary small towns across America, most Jews living in Lancaster during the first two decades of the 20th century were involved in retail businesses. While most businesses were concentrated in Lancaster’s downtown district, the range of services provided by Jews varied greatly during this time period. For example, several Jewish families were involved in the grocery industry including Jacob Balas, who owned an independent store in town prior to moving to Michigan during the 1930s,[12] Isaac Bogroff, Jacob Mellman, Morris Yablok, who each owned a portion of the Lancaster Fruit Company, Alex Schlesinger, who operated a grocery store in town until the late 1930s, and Samuel Silver, who was a longtime produce dealer in the Lancaster Market House. In addition, several Jewish businessmen made a living as clothing merchants. Kessel’s Fashion Shop, The Hub Clothing Company, and The Famous Men’s Store, under the proprietorship of Leo Kessel, William Fine, and Al Wittekind respectively, were examples of early Jewish-owned clothing businesses. Other Jewish-owned businesses in Lancaster during this period include the Hippodrome Theater, The Syndicate, a dry goods store on Main Street, Rothbardt’s Dry Goods, and Wannamaker’s, a tailor shop on North Broad Street.[13]

Another Jewish-owned business to be established in Lancaster during this time period was the Epstein Shoe Company, which would become well-known as the oldest retail store in Fairfield County.[14] Founded by the brothers’ Clarence and Charles Epstein in 1916, Epstein’s Shoes originally was located inside the Smith Building on the corner of Columbus and Main Street before temporarily closing during World War I, when Clarence and Charles enlisted in the armed forces. Like many Jews in Lancaster during this time period, Clarence and Charles were themselves recent immigrants to the United States, arriving in 1905 and 1911 respectively. Eventually, Charles also went on to establish Arcade Shoes in Logan, Ohio, which itself was in business for over fifty years. Given the longevity of their family businesses, the Epstein’s would become among the best-known Jewish families in Lancaster and Logan.

Expansion and War: Lancaster’s Jewish Community, 1900-1926

As more Jews began to establish roots in Lancaster, families also developed. One of the defining characteristics of Lancaster’s Jewish community during the first two decades of the 20th century was a modest baby boom. The need to provide a religious education for these children led to the creation of a Jewish Sunday School in Lancaster by 1917. Many of these children would go on to contribute significantly to the community’s growth in the 1930s and 1940s, and, with future growth in mind, the community began to look for a permanent synagogue by the mid-1920s. Lena and David Altfater together had four children after their arrival in Lancaster: Abraham, Jacob, Joseph, and Ruth. The Altfater children were, like most Jews in Lancaster, integrated into their community, and frequently socialized with non-Jews. For example, as a teenager Jacob participated in the “Barracks Baseball” program,[15] and his sister Ruth worked in a grocery store. Another significantly sized family in town was the Rothbardts, who were comprised of Gabriel and Rose Rothbardt and their children Norman, Bernard, Adolph, and Miriam. The Rothbardts did not remain in Lancaster very long, however, rather by 1924 the family had already relocated to Hannibal Missouri, where Gabriel had opened another business.[16] A more lasting family presence in town was established by Samuel Silver and his wife Fannie who together had six children: Eva, Frank, Phillip, Maurice, Sadye, and Alfred, who died at age five of pneumonia.[17]

Additionally, in 1908 the Molars had their second child, a boy named Jacob. He would eventually be joined by three younger siblings, two brothers, Noah and George, and a sister Clara. What is especially notable about Jacob Molar is that he would go on to become one of Lancaster’s oldest Jewish residents, and as such he witnessed much of the history of the area’s Jewish community. It is in part because of this that Jacob Molar was interviewed in 1996 by The Columbus Jewish Historical Society regarding his experiences in Lancaster. This interview has become one of the most accessible online sources highlighting the history of Lancaster’s Jews.[18] As a child Jacob attended South School in Lancaster, which was located near his father’s business, and it is likely that he was an active member of the Junior Council, a Jewish youth organization in Lancaster, and the Lancaster Hebrew School. References to these organizations can be found in archives of The Ohio Jewish Chronicle, which published a “Lancaster Notes” column in the “Social and Personal” section of the newspaper periodically in 1922-1923. Some of the activities undertaken by these organizations include social dances and holiday plays.[19]

Not every development in Lancaster during this period was positive. On April 7, 1917, the United States entered World War I on the side of the Allies, and Lancaster’s Jews, like their non-Jewish neighbors, were called upon to enter the service. In total at least eight Jewish men from Lancaster served their country during the war: Leo Kessel, Clarence Epstein, Charles Epstein, Harry Kurchick, Jay Altfater, Earl Shenker, Harry Abram,[20] and Solomon (Sol) Rising.[21] Private Sol Rising’s experiences during the war were followed particularly closely in Lancaster due to the fame he won himself for bravery during the Battle of the Marne as a member of the 42nd Infantry Division. One particularly interesting reference to Sol Rising can be found in the October 18, 1918 edition of The Lancaster Daily Eagle, which published a letter he had written from the Western Front describing the difficulties of observing the Jewish new year, Rosh Hashanah, while on duty:

Dear sister, I would like to go to church during the New Year, but I can’t. Last year when I was in Camps Mills I went to New York, but here it is different, you have to go to the trenches instead of going to church. I just spoke to the Chaplain from our regiment about our New Year, so he told me he will try his best to send us Jewish boys to church. In case I don’t get to go to church, you will have to pray for me and for all our allied soldiers for a victory and a safe return to our homes.[22]

While some of Lancaster’s Jews went off to fight, others aided in the war effort on the home front by establishing the Jewish Welfare Society of Lancaster. This organization actively volunteered with the American Red Cross, and raised funds to purchase Liberty Loans and the Community Chest campaigns. In addition, its members were described as, “always willing to work.”[23]

During this same time period, evidence for the existence of another Jewish service-based organization emerges in Lancaster. Originally termed the Jewish Sisterhood[24] and later renamed The Council of Jewish Women, this new women’s organization of approximately 18 members engaged in a number of service projects including, sewing blankets for infants at the Jewish Infants Hospital of Ohio and providing holiday meals and activities to the approximately sixteen Jewish residents of the Boys Industrial School.[25] By 1922, the Lancaster chapter of The Council of Jewish Women was fully recognized by the executive office of The Council of Jewish Women, testifying to the strength of the organization. Thus Lancaster became home to the 210th Section of The Council, and its first President was Rose Rothbardt.[26] Bi-weekly meetings were held throughout the year in which members took turns hosting the organization within their homes. Members of The Council also organized social gatherings for the Jews of Lancaster and surrounding areas. Some of the most common events included dances, euchre tournaments, and picnics. Larger events also drew participants from the Columbus Jewish community, such as the 1924 “Grand Social Picnic” held at Fern Cliff Farm.[27] Proceeds from ticket sales at these events were used to support the organization’s charitable activities, and to further the development of Lancaster’s Jewish community.

A Time to Settle Down: The Purchase of the German Lutheran Church

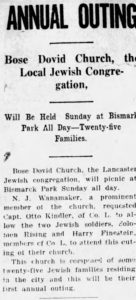

A significant undertaking for the Jewish community during this period was obtaining a permanent place of worship. By 1914, the number of Jews in Lancaster had grown large enough for regular religious services to be organized, which utilized rented spaces downtown or private homes. Some locations for services included: the Knights of Columbus Hall on West Main Street,[28] Bininger Hall on South Columbus Street, and the Woodman and Laurel Lodge.[29] This early religious association called itself Beth David, after the biblical King David and David Altfater, who at the time was recognized as the chief leader among Lancaster’s Jews. One of the first public references to Beth David, which is also spelled Bose Dovid in some sources, occurred in 1917, when The Lancaster Daily Eagle ran a small article highlighting the congregation’s first annual picnic outing to Bismarck Park.[30] Another early reference to Beth David occurred in 1922, when the local paper ran a story on the group’s celebration of Hanukkah.[31] As the Jewish community continued to grow, however, rented spaces, private homes, and parks began to prove insufficient for its needs, and a committee, under the leadership of David Altfater, Jacob Moskowitz, and Morris Molar, began to look for a building in town suitable for use as a synagogue.

An opportunity to purchase such a building presented itself in May of 1926, when the Emanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church, also known to residents as the German Lutheran Church due to the use of German in its services, elected to sell its sanctuary, located at 131 East Chestnut Street, in order to move to a larger property nearby. After deliberation, the members of the Lutheran congregation offered to sell their sanctuary for $11,000,[32] or approximately $152,500 after adjusting for inflation in October of 2017, to the Jewish community which accepted the offer. The ability of Lancaster’s Jews to put forth such a significant sum of money testified to the community’s strength at this point in time. According to the 1926 Beth David Treasurer’s Report, at this time there were 25 dues paying members of the congregation who represented 21 families. In addition, 24 individuals also contributed holiday donations to the congregation.

Outlying Jews: An Overview of Lancaster’s Satellite Communities

One interesting piece of the 1926 Treasurer’s Report, which ought to be examined before relating the opening of Lancaster’s synagogue, is the evidence of Jews living in small towns surrounding Lancaster during this time period. These individuals also played a significant part in Jewish life within Lancaster and in the procurement of a permanent synagogue in the city. One especially notable family were the Shenkers, who resided in Bremen, a small village ten miles east of Lancaster, and near the town of New Lexington. Two brothers, Abraham and Louis, were the patriarchs of the family, and both immigrated to the United States from the Russian Empire around the year 1900. Once established in Ohio, both brothers were prominent in the oil business[33] selling oil well supplies. Eventually Louis left New Lexington for Lancaster with his wife, Anna, and his children Martin, Jeanette, and Emmanuel. In addition, Abraham, as a longtime member of the Masons and the Elks Lodge,[34] reflected how socially integrated many Jews in this area were into the lives of their communities. Other Jews outside Lancaster who maintained ties to the city’s Jewish community included: Morris Cohen, a scrap metal dealer in New Lexington, Harry Cowen, a resident of Logan, and Moses Steinberger, an immigrant from Poland residing in Chillicothe.

One of the more distant families to maintain connections to Lancaster’s Jewish community were the Neimans of Nelsonville, a small town located thirty miles southeast of Lancaster. Albert and Celia Neiman were themselves immigrants from Poland who arrived in the United States around 1914. Once established in Nelsonville, the Neimans opened up a junk yard, and raised four children: Sam, Lillian, Ruth, and David. Other Jewish families in Nelsonville at the time included, the Davis family, Radens, and Shamanskys. Additionally, Jewish families from Glouster and Chauncey, also located in Athens County, would travel similar distances to Lancaster in order to observe Jewish holidays with Congregation Beth David.[35] During the 1920s, the Goldbergs were the most prominent Jewish family in Glouster. Benjamin Goldberg, an immigrant from Hungary and the head of the family, owned the village General Store for over fifty years, and was an active member of Kiwanis International, the Tifereth Israel Brotherhood, located in Columbus, and the Masons. He also had a wife, Bertha, who was born in Pennsylvania, and two children, Daniel and Sharon.[36] During this same period, in the village of Chauncey the Wilsons, a large family of six children, were the most prominent Jewish residents. A merchant by trade, Isaac Wilson died unexpectedly in 1919 while undergoing a surgical operation, leaving his wife Sarah to raise the children. One of these children, Louis also passed away at a young age while fighting in World War I.[37] Like many Jews of his time period, Isaac Wilson was himself an immigrant from the Russian Empire who arrived in the United States, and initially supported his family through the peddling goods. With time, he was able to expand his business and open up a full-fledged shop in Chauncey. Other contemporary Jews that resided in Chauncey or Glouster included, Herman Luckhoff, Max Altman, and the Trasin family.

A Synagogue on Chestnut Street: The Dedication of Congregation B’nai Israel

On February 27, 1927 Jews from all across Ohio converged on Lancaster for the dedication of the town’s new synagogue, B’nai Israel. Later, on Monday, February 28th, The Lancaster Daily Eagle ran a lengthy, front-page article profiling the synagogue’s opening, and it was reported that over 500 people attended the dedication services. These ceremonies were especially notable for having several of Columbus’s preeminent Jewish leaders in attendance including, Rabbi Jacob Tarshish of Temple Israel, Rabbi Isaac Werne of Congregation Agudas Achim, and Rabbi Leopold Greenwald of Congregation Beth Jacob. These rabbis represented many of the largest and oldest Jewish congregations in Columbus, and both the Orthodox and Reform movements. In addition, the presence of these religious leaders testified to the strength of Lancaster’s Jewish community, and to the close ties it enjoyed with Columbus’s Jewish institutions. Further, news of the synagogue’s dedication was reported in Jewish newspapers as far away as Cleveland.[38]

In addition to featuring several prominent Jewish leaders, the dedication ceremonies for B’nai Israel also included speeches from non-Jewish members of the Lancaster community. These included Henry Albert Alspach, the Mayor of Lancaster, who stated that he, “represented all the people, and would have the interest of all creeds of Lancaster at heart.”[39] An address was also delivered by the Reverend Benjamin Paist, who served the nearby First Presbyterian Church, on the need for religious tolerance. The presence of these, and other non-Jewish leaders, testifies to the strong relations between Lancaster’s Jewish and non-Jewish communities, and the overall integration of Jews into the civic life of Lancaster. In total three services were offered throughout the day, and in the evening a banquet was prepared for over 250 guests by the Lancaster Council of Jewish Women. Additionally, over $2,000, or approximately $28,000 after adjusting for inflation in October of 2017, in donations were collected throughout the day.[40]

Rabbi Samuel Shapiro was selected to continue his services in Lancaster as the new Congregation’s first rabbi. In addition, Rabbi Shapiro also worked as Lancaster’s Hebrew school teacher and shochet, or kosher butcher. It is estimated that around 25 families were full members of Congregation B’nai Israel at the time of its opening.[41] Of these members, Clarence Epstein, William Fine, Albert Long, Leo Kessel, Morris Molar, Louis Shenker, Abraham Snyder, and Morris Yabrove are notable for having signed the B’nai Israel Articles of Incorporation one year earlier in 1926. It was also at this time that Congregation Beth David changed its name to B’nai Israel for reasons that are not entirely clear. Morris Molar was recognized under the Articles as the first President of B’nai Israel, succeeding Jacob Balas who presided over Beth David. Additionally, David Altfater also moved to Logan around this time and withdrew from active participation in the affairs of the synagogue.

A Time of Transition: Lancaster’s Jewish Community in the 1930s

Due to the presence of strong, secure industries in town, such as the Goodman Shoe Factory and Anchor Hocking, a producer of glassware, Lancaster was spared the worst effects of the Great Depression which engulfed the United States from October 29, 1929 to 1939. During this period several Jewish families did leave Lancaster, however, but new individuals also moved into town, which allowed the size of the community to remain stable. Families who left included the Bogroffs, Balas, Schlesingers, and Yabroves. New arrivals to Lancaster include the Levines, Weisenbergs, and Franklins. Another transition which occurred involved Lancaster’s rabbinic leadership. Rabbi Shapiro left Lancaster in 1931 after serving seven years as rabbi to take a position with Congregation Ohev Sholom in Lewistown, Pennsylvania. At the time, it was noted in The Lancaster Daily Eagle that Ohev Sholom possessed a larger membership than B’nai Israel.[42] Due to this fact, it is most likely that Ohev Sholom was able to provide Shapiro with a larger salary than the $125.00, or approximately $2,000 after accounting for inflation in October of 2017, a month he received in Lancaster.

Lancaster would not remain without a religious leader for very long, however, for by 1932 Rabbi Julius Baker, an immigrant from Yedwobne, Poland,[43] had taken up the vacant post. Rabbi Baker would go on to serve as Rabbi of Congregation B’nai Israel for 25 years, making him the longest serving rabbi in the congregation’s history. As Rabbi, Baker ensured that the Jewish youth of the city were provided with a religious education that was “along the same lines as that received by youth of large communities”,[44] and he continued to act as the city’s shochet. Additionally, Baker was noteworthy for his exceptional knowledge of Talmud, which is a compilation of Judaism’s oral traditions, and he went on to write a collection of sermons, Pri Yehudah, and edit the text of Sefer Yedwabne, which discussed the history of Yedwobne’s Jewish community up until its destruction during the Holocaust.[45]

While Baker’s congregation was located in Lancaster, for most of his time as rabbi he maintained his residence in Columbus, where he held many leadership roles, including serving as President of Mizrachi, a religious Zionist organization. This is reflective of the close ties between Columbus and Lancaster Jewry during this time, and how many Jewish residents of Lancaster were actively involved in the Columbus chapters of philanthropic organizations, such as Hadassah and B’nai B’rith. Additionally, Lancaster Jews contributed charitable donations to Jewish institutions across the state, including the Jewish Orphan Asylum, now known as the Bellefaire JCB, and the Orthodox Old Home, now known as Menorah Park, in Cleveland. Some of these donations were organized through B’nai Israel or the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, which succeeded the Lancaster Council of Jewish Women by the early 1930s. Of the charitable fundraisers sponsored by the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, an annual dance was especially popular and well-attended by Jews from across Central Ohio.[46]

In addition to organizational and charitable pursuits, Jewish life in Lancaster was also defined by religious lifecycle events, of which marriage was an especially important component. The first Jewish wedding to take place in Lancaster occurred on August 15, 1926 when Hilda Molar, the oldest daughter of Morris and Rachel Molar, was married to Joseph Weinthraub at B’nai Israel. This wedding was especially notable for being the first community event to take place inside the new synagogue, and it received significant coverage in the “Society” section of The Lancaster Daily Eagle.[47] In total, over 100 out-of-town guests attended the wedding, which was officiated by Rabbi Werne, and, at the conclusion of the ceremony, the Molar family donated the gold and purple chuppah, or wedding canopy, to the synagogue for use by future brides. Hilda, like many brides who wed out-of-town grooms, left Lancaster following her marriage to live with her husband in his hometown of Cleveland. This pattern would significantly contribute to the decline of Lancaster’s Jewish community in the years to come.

During the 1930s, however, Lancaster’s Jewish population continued to remain relatively stable, and as more children grew older, other significant weddings took place in Lancaster. The next large wedding occurred on June 27, 1928 when Jeanette Shenker, the daughter of Louis and Anna Shenker, wed Harry Rubin of Columbus. In total, around 500 guests attended the ceremony, which was officiated by two Columbus rabbis, Solomon Rivlin of Tifereth Israel and Leopold Greenwald of Beth Jacob.[48] In 1931, Mary Bass, the oldest of seven children born to Sarah and Louis Bass, wed Abe Weissman of Columbus at B’nai Israel in a ceremony performed by Samuel Shapiro. This wedding was of special interest in Lancaster since the bride’s father, Louis Bass had been killed eleven years before after his car was struck by a freight engine owned by the Hocking Valley Company while crossing the High Street railroad tracks. At the time, the accident was described as one of “the worst ever seen in Lancaster”.[49] For many in Lancaster, the wedding of Mary Bass represented her family’s ability to move forward despite this tragedy.

Other contemporary in town weddings covered by The Lancaster Daily Eagle include the marriages of Katherine Silver and Al Dworkin in January 1934, Lillian Schlesinger and Robert Mellman in February 1934, and Rachel Bass and Jacob Cohen in 1936. Each of these weddings attracted over one hundred guests, and both Lillian Mellman and Rachel Cohen left for Columbus after their weddings. Katherine Dworkin, however remained in Lancaster with her new out-of-town husband, and eventually went on to become the President of the B’nai Israel Sisterhood and raise two children, Carole and Michael, who eventually moved to Columbus. In addition, Katherine, like many Lancaster Jews of this time period including Edith Bass, Jacob Bass, Eva Silver, and Sadye Silver, found employment with Anchor Hocking. Jacob Bass is especially noteworthy in that he was able to rise through the ranks of Anchor Hocking to become one of the company’s executives by the time of his retirement.[50]

War and Prosperity: Jewish Life in the 40s and Early 50s

While the 1930s was a difficult decade for many Americans, residents of Lancaster were generally spared the worst effects of The Depression due to the presence of industries, such as Anchor Hocking, an important manufacturer of Depression glass, which remained active throughout the decade. This stability in the town’s economy also typically allowed Jewish-owned businesses to keep their doors open even during the most severe years of the Depression. One especially visible sign of the Jewish community’s financial stability could be seen in 1940, when the mortgage for Congregation B’nai Israel was paid off in full. Rabbi Baker was credited with prompting his congregants during Yom Kippur to push to pay off the mortgage, and in total around 40 people contributed to paying off the debt, including some individuals who had moved away from Lancaster.[51] Two prominent businessman, Abraham Snyder and Sam Segal, each contributed $1,000, or approximately $17,600 after adjusting for inflation in October of 2017, towards paying off the synagogue’s debts. These two gifts comprised the largest donations received by the congregation during this period. Abraham Snyder was himself an immigrant from Poland who had achieved success in the oil industry, while Sam Segal was a resident of Chillicothe who had emigrated from Estonia. Once in Chillicothe, Segal helped to establish a successful business, the Segal-Schadel Company, which produced paper products. On March 16, 1941, the festival of Purim, the members of B’nai Israel threw a large party to celebrate the burning of the congregation’s mortgage, which was attended by around 150 people. Attendees included Jews from across Central Ohio, and some especially notable participants were, Morris Molar, who continued to serve as President of B’nai Israel, Clarence Epstein, the Congregation’s Secretary and Treasurer, and Jerry Mellman, who performed the burning of the mortgage.

Several months after this joyous event, however, both Jewish and non-Jewish residents of Lancaster would find themselves once again called upon to serve their country as a result of the December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese military. This battle caused the deaths of over 2,400 Americans, and led to the entry of the United States into World War II. In total, at least seven Jews from the Lancaster area served during the war: Jacob Bass, Morton Epstein, Victor Epstein, George Molar, Robert Neiman of Nelsonville, Abraham Shatz of Logan, and Maurice Silver. One of these soldiers, Victor Epstein, also numbered among the over 400,000 American casualties during the war.[52] In addition to the sacrifices made by those in the service, throughout the war Americans on the home front also took steps to support the war effort and aid those adversely affected by the actions of the Axis powers. Lancaster’s Jews in particular organized to raise money and collect clothes to assist their coreligionists who found themselves as refugees in Eastern Europe. Additionally, members of the B’nai Israel Sisterhood also collected sales stamps to redeem with the State of Ohio. The proceeds raised were used to support various charitable causes.[53] Finally, throughout the war special prayers for those in the armed forces were also offered at B’nai Israel as part of the High Holiday services.

After the end of World War II on September 02, 1945, however, the United States entered a period of relative prosperity and stability. This newfound security soon caused memories of anxiety and scarcity to diminish in the minds of many Americans. Lancaster also shared in this post-war economic boom, and it was during the years immediately following World War II that Lancaster’s Jewish community achieved its largest size.[54] The primary reason for this expansion within the community was the growth of already established families in town. For example, Morton Epstein, the brother of Victor Epstein, and his wife Leila raised three children named Adele, David, and Vicki. Another family which continued to grow were the Molars. While both daughters of Morris and Rachel Molar moved out-of-town following marriage, two of their three sons, Jacob and Noah, continued to work in the family auto parts business, which allowed them to create their own households in Lancaster. Noah and his wife Shirley together raised three children, Ronald, Susan, and Barry; while Jacob and Elizabeth (Betty) Molar also raised three children, David, Nora, and Sharon. In addition to natural growth, a small number of new residents, such as the Fogols, Loppers, and Swartzs, also arrived during the late 40s and early 50s in order to work with companies such as Diamond Power, a supplier of industrial equipment, and Anchor Hocking. Another notable arrival was Fred Hillman, a Holocaust survivor who went on to establish Lancaster Sales.

Signs of Decline: Lancaster’s Jewish Community c. 1955 to 1970

Despite a brief period initial post-war growth, however, by the mid-1950s Lancaster’s Jewish community began to show signs of decline as more individuals born during the late 1920s and 1930s began to leave town than were replaced. One example of this trend can be seen in the person of Stanton Abram, who was the son of long-time Lancaster residents Harry and Amelia Abram. After graduating from dental school around 1950, Stanton chose to serve in the Coast Guard, where he eventually became a mobile unit commander.[55] Upon re-entering civilian life, he went on to establish a practice in Cleveland, which he ran for many years before retiring to Florida.[56] While his father had made a comfortable living in Lancaster as manager of the Palace Theater, Stanton was able to take the skills he had learned while in higher education to larger cities which afforded more economic opportunities. This tendency of young people to not return to Lancaster after their graduation from various universities was later cited by Alan Shatz, the last President of B’nai Israel, as the leading cause of the community’s dissolution.[57]

Another blow to Lancaster’s Jewish community occurred in 1957, when Rabbi Baker decided to take a full-time position as Head Rabbi of Ahavas Sholom, an Orthodox congregation in Columbus. While he had been commuting from Columbus to Lancaster for several years, there is record that Baker was still able to offer daily services, at least for a brief period of time, in Lancaster, and that he brought other Columbus rabbis, such as Samuel Rubenstein of Congregation Agudas Achim to Lancaster in order to teach classes on Jewish law.[58] Undoubtedly, Rabbi Baker’s departure from B’nai Israel was a significant loss for the congregation, which was too small by the late 1950s to effectively obtain the services of another full-time rabbi. One of the most damaging effects of not having a rabbi was the decline in religious education. Without anyone to teach Hebrew school, Jews in Lancaster who wished to provide a formal religious education for their children now had to travel to Columbus in order to access these programs. Illustrating this point is the reality that the last bar mitzvah, or coming of age ceremony, held at B’nai Israel occurred around 1948, when Jacob (Jack) Shatz was called to read from the Torah for the first time.[59] After this point young Jews from Lancaster would travel to Columbus for their Hebrew classes and bar or bat mitzvah ceremonies. This likely contributed further to the departure of Jewish families from Lancaster.

In addition to facing declining demographics, and the loss of its local rabbi, the Jewish community also confronted the death of Morris Molar on December 10, 1960.[60] Morris had served as B’nai Israel’s President since 1926, and he was an invaluable member of the wider community. Another tragedy struck less than two months later when on Sunday, February 5, 1961, B’nai Israel caught fire and sustained heavy damage. At the time it was reported in The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette that “every fireman on and off duty was notified to report… (and that) fireman were on the scene for 2 [sic] and a half hours.”[61] In addition, The Logan Daily News reported that the heat from the fire was so intense that the congregation’s stained glass windows had melted and the building’s paint peeled from the walls.[62] Eventually, it was determined that the fire had begun in the basement furnace room, and that approximately $15,000, or around $124,000 after accounting for inflation in October of 2017, would be needed to repair the congregation. Due to the efforts of Jacob Molar and Clearance Epstein, however, the congregation’s Torah scrolls were saved from the fire.[63] This allowed the synagogue’s twelve remaining member families to conduct services in the congregational social hall, which was undamaged by the blaze. It is also noteworthy that shortly after the fire Reverend Sidney Waddington of St. John’s Episcopal Church, which was located a few blocks from B’nai Israel, offered the congregants space inside the church for Friday night Shabbat services.[64] While this offer was declined by the members of B’nai Israel, it does nonetheless demonstrate the existence of inter-faith cooperation and respect in Lancaster. Within a couple of years, services were restored to the sanctuary of B’nai Israel following the building’s renovation. This new building, however, lacked the upstairs balcony formerly designated as woman’s seating.[65] While it is not known for certain why the women’s balcony was not rebuilt, it is possible that this change was a recognition of the congregation’s declining membership and the need for fewer seats.

Despite the challenges of the late 50s and early 60s, members of Lancaster’s Jewish community continued to organize communal events for coreligionists, and to make an impact on the larger Lancaster community. Much of the work done to reinforce the Jewish community during this time period was performed by members of the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, who oversaw both fundraising and holiday events on behalf of their congregation. One type of fundraising event that was especially popular during this period were community rummage sales, which were advertised in The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette. In addition, the Sisterhood also sponsored an annual Hanukkah dinner for the Jewish community and several other informal holiday events. These types of gatherings became an increasingly important way for many of Lancaster’s Jews to maintain a sense of community as their numbers continued to decrease. Within the larger Lancaster community, Jews were involved in a number of civic and interest-based organizations including, The American Legion, the Lancaster Area Chamber of Commerce, the Lancaster Community Concert Association, and Toastmasters International. In addition, Jews also held leadership positions in charitable organizations such as, Maywood Mission, the Red Cross, and United Way.

Signs of the Times: The Disappearance of Lancaster’s Satellite Communities

As the number of Jews in Lancaster continued to decrease, the same pattern of youth migration previously referenced caused the virtual disappearance of its satellite communities by the 1960s. One especially notable satellite community of Lancaster was Logan. According to Howard Epstein, the son of Charles Epstein, Logan was home to four Jewish families during the 1940s.[66] Evidence also exists within the Ohio Jewish Chronicle archives to demonstrate that members of the Eichel, Epstein, Sharff, and Shatz families all lived in town during this time period. By 1970, however, all of these families would no longer live in Logan. The reasons behind each family’s departure are similar to those of families in other communities, such as Chauncey, Glouster, and Nelsonville, and can be used to illustrate how other satellite communities declined during the same period of time.

While most Jewish families in Logan were engaged in business, each had its own unique trade. Emil Eichel was himself a resident of Logan for 35 years with his wife Johanna, and he supported his family primarily through a bakery. At the time of his death, however, it was already noted that all his children had moved to Columbus, which afforded greater economic opportunities.[67] Charles Epstein, like his brother Clarence, was an established shoe merchant whose store was open for decades. Howard, however decided to leave his hometown in order to attend a university in Cleveland. After graduation, he remained in Cuyahoga County and worked with the Mandel Jewish Community Center for a number of years.[68] Sam Sharff was the founder of Sharff Stores Inc. and Ladies Ready to Wear Stores.[69] Sam and Pearl Sharff also eventually left Logan, however, to be closer to their son, Earl, who had moved to Newark moved following his marriage to Marjorie Waldman. Finally, Abraham Shatz, an immigrant from Poland, established himself as a junk dealer. In total, his business, Logan Auto Parts & Wrecking, was in operation for about 20 years. In addition, his wife, Ruth was a teacher at the local elementary school.[70] Abraham did not have any children who he could hand his business on to, however, and his brother, Albert Shatz had himself opened up his own business, Lancaster Auto Parts, which was passed down to his son and grandchildren. Therefore, after the death of Abraham Shatz in 1966, the Shatz family no longer had any business presence in Logan. With their businesses closed or sold, Logan’s Jewish community ended.

The Closing Years: Lancaster’s Jewish Community 1970-1993

While Jewish families were disappearing in many areas surrounding Lancaster, during the 1970s and 1980s, the decline of Lancaster’s Jewish community was slowed somewhat by the arrival of a small number of new families in town. Most of these families, including the Heibers, Gorensteins, and Axes, were connected to the healthcare industry. Specifically, Dr. Ronald Heiber moved to Lancaster in order to practice orthodontics, and he continued to maintain his own business, Central Ohio Orthodontics, into the second decade of the 21st century. Dr. Aryeh Gorenstein similarly moved to Lancaster with his wife Marcie in order to practice otolaryngology. Like Dr. Heiber, he also continued to practice in town as of 2017. Unlike the Heibers and and Gorensteins, however, the Axes moved to Lancaster in order for Vicki Axe to take a position as Cantor at Temple Israel, the oldest synagogue in Columbus. Once established in Lancaster, however, Vicki’s husband Harold also opened an independent medical practice, which specialized in allergy relief and immunology.[71] Another notable new arrival was Gregg Marx, who moved his family to Lancaster after he secured a position with the Fairfield County Prosecutor’s Office in 1982. With time, Gregg would be elected as Fairfield County’s Prosecuting Attorney from 2011-2016, making him the first Jew known to have obtained a countywide office.[72]

While these new families made significant contributions to Lancaster, and to the Jewish community, their numbers were not sufficient enough to reverse two decades of demographic decline. Despite this ongoing challenge, throughout the 70s and 80s, B’nai Israel continued to be utilized on the High Holidays. For these services, the congregants typically hired a student rabbi or cantor from out-of-town. For example, in the early 1970s, two cantors from New York named Samuel Graff and Stephen Brenner were hired to lead services, while in the 1980s rabbis from Columbus tended to be utilized. Additionally, during the 1980s, B’nai Israel also began to advertise its services in the Ohio Jewish Chronicle in an effort to boost attendance. The last advertisement placed in the paper was published on September 21, 1989, the 63rd consecutive year of High Holiday services at B’nai Israel.[73]

Nearly four years after this final High Holiday service, the remaining members of B’nai Israel elected to sell their congregation. While some congregants had advocated selling the synagogue as early as 1984, others held out hope that the number of Jews in Lancaster might increase, allowing the congregation to be kept in use. One significant factor in the decision to ultimately sell the congregation was the mounting costs of keeping the sanctuary repaired, which were estimated at $40,000 in 1993.[74] In addition, declining membership had prevented the synagogue from opening for three years by 1992.[75] Finally, on August 07, 1993, The Lancaster-Eagle Gazette announced that B’nai Israel would be closing after 67 years. The last officers of the congregation who approved the final sale were the following, Alan Shatz, President, Gregg Marx, Vice President, Fran Duchene, Secretary, and Morton Epstein, Treasurer.

Following the sale of B’nai Israel, the members of the congregation sought to ensure that the memory of their synagogue remained for future generations living in Lancaster by establishing the “B’nai Israel of Lancaster Jewish Book Fund”, which allows the Fairfield County Library to expand its Judaica offerings every year.[76] In addition, proceeds from the sale were also used to establish the “B’nai Israel Scholarship” at Columbus Torah Academy, and a donation was also made to Congregation Ahavas Sholom for the perpetual upkeep and display of the disbanded congregation’s yahrzeit, or memorial, plaques. Finally, the synagogue’s three Torah scrolls were also donated to Jewish schools. One was given a few years before the sale to the Portland Jewish Academy in 1988, while the two remaining Torahs were given to Columbus Torah Academy after 1993. The congregants had learned of the need of Portland’s Jewish school for a Torah through Vicki Epstein, who had moved to Portland following her marriage to Harold Frolich.[77] By taking these actions, the members of B’nai Israel sought to ensure that their congregational legacy would continue to help further Jewish education.

Conclusion

While the closure of B’nai Israel in 1993 marked the end of organized Jewish life in Fairfield County, it did not mean Jews no longer lived in Lancaster, or that their contributions ceased to have any influence on the larger community. Today, Jewish children in Columbus and Portland are still impacted by the legacy of B’nai Israel’s congregants, and residents of Fairfield and Hocking counties still enjoy civic and philanthropic organizations which Jews once took an active role in maintaining. In addition, Jews have also contributed significantly to the region’s economic development. These contributions have taken many forms through the years including, connecting Lancaster with other communities in the mid-19th century, helping to promote a thriving downtown commercial district in Lancaster during the early 20th century, and augmenting Fairfield County’s medical capabilities during the latter years of the 20th century.

Perhaps the most lasting contribution made by Jewish residents of Fairfield and Hocking counties, however was expanding their area’s overall level of tolerance. While anti-Semitism appears to have been common in the region during the mid-1800s, as is suggested through newspaper advertisements, by the mid-20th century Jewish residents in the area reported experiencing little anti-Semitism. While attitudes towards Jews certainly did not change overnight, with time the positive impact Jews made on their community won them the respect of their non-Jewish neighbors. Through contributions such as these, the Jews of Fairfield and Hocking counties demonstrated how many different groups have come together to create the region as it is known today. This diversity has been a source of strength Fairfield and Hocking counties, and it truly ought to be considered a point of pride for their residents.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Beal, Eileen Beal. “Giving Voice to Small-Town Jews.” Cleveland Jewish News (Cleveland, 0H), July 04, 1997.

“Council’s Rapid Growth Continues.” The Reform Advocate 63, no. 1 (1922): 574.

Epstein, Howard. “Just a Home on the Highway, but It Had a Shabbos Light in the Window.” Cleveland Jewish News, June 24, 1966.

Maddux, Jason. “B’nai Israel closing doors after 67 years.” The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, August 07, 1993.

Molar, Jacob. Jacob Molar: Longtime Lancaster Resident. By Naomi Schottenstein. Columbus Jewish Historical Society, December 8, 1996.

Molar, Morris.“Lancaster Jewry Expresses Appreciation.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, March 4, 1927.

Stimer, Darla Stimer. “Keeping The Faith.” The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, October 05, 1992.

Thurston, Trista. “Prosecutor Set to Retire by Year’s End.” The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, December 18, 2016.

Newspapers Utilized:

Cleveland Jewish News (Cleveland, OH).

Jewish Review and Observer (Cleveland, OH)

Ohio Jewish Chronicle (Columbus, OH).

The Lancaster Daily Eagle (Lancaster, OH).

The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette (Lancaster, OH).

The Logan Daily News (Logan, OH).

The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH)

The Weekly Lancaster Gazette (Lancaster, OH).

Secondary Sources

Contosta, David R. Lancaster, Ohio, 1800-2000: Frontier Town to Edge City. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 1999.

Dill, Lisa R., and Dennis E. Miller. Fairfield County Treasures. Lancaster: North End Press, 1988.

Fetters, Ginny. “Congregation B’nai Israel.” Fairfield Heritage Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1986): 2-6.

Goslin, Charles. Crossroads and Fence Corners: Historical Lore of Fairfield County, Vol. 2. Lancaster: Fairfield Heritage Association, 1980.

Hasia Diner. “Peddling as a Profession: A Widespread Activity.” Immigrant Entrepreneurship German-American Business Biographies. February 11, 2014. https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=191.

“History of Lancaster.” City of Lancaster Ohio. September 29, 2017. https://www.ci.lancaster.oh.us/394/History-of-Lancaster.

Rabinowitz, Ann. “The American Jew Who Fought for the Boers During the Second Boer War (1899-1902.” JewishGen. http://jewishgen.blogspot.com/2009/12/american-jew-who-fought-for-boers.html.

Snider, Van A. Fairfield County In The World War. Lancaster: Mallory Printing Company, 1920.

Footnotes

[1] “History of Lancaster,” City of Lancaster Ohio, September 29, 2017, https://www.ci.lancaster.oh.us/394/History-of-Lancaster

[2] “Local Intelligence,” Weekly Lancaster Gazette, September 29, 1853.

[3] Hasia Diner, “Peddling as a Profession: A Widespread Activity,” Immigrant Entrepreneurship German-American Business Biographies, February 11, 2014, www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org. https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=191

[4] “Watches and Jewelry,” Weekly Lancaster Gazette, June 14, 1850.

[5] “Clothing at Wholesale and Retail,” Weekly Lancaster Gazette, January 11, 1850.

[7] Ginny Fetters, “Congregation B’nai Israel,” Fairfield Heritage Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1986): 2.

[8] Fetters, “Congregation B’nai Israel,” Fairfield Heritage.

[9] Letter from Dee Kline (granddaughter of David Altfather) to the author, August 16, 2017.

[10] Obituary of Rachel Molar, Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, January 01, 1951.

[11] David R. Contosta, Lancaster, Ohio, 1800-2000: Frontier Town to Edge City (Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 1999), 175.

[12] 1920 U.S. Census, Fairfield County, Ohio, population schedule, Lancaster; p 7B, Jacob Balas; digital image, Ancestry.com. http://ancestry.com.

[13] Fetters, “Congregation B’nai Israel,” Fairfield Heritage.

[14] “A lot has changed since women wore high-buttoning, black shoes,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, February 26, 1988.

[15] “Barracks Baseball,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, June 15, 1917.

[16] “Gabriel Rothbardt Visits In Lancaster,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, July 31, 1924.

[17] “Little Son of Samuel Silver Passes Away,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, April 27, 1917.

[18] Jacob Molar, interview by Naomi Schottenstein, Oral Histories, The Columbus Jewish Historical Society, December 8, 1996.

[19] “Lancaster Notes,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, December 15, 1922.

[20] Van A. Snider, Fairfield County In The World War (Lancaster: Mallory Printing Company, 1920), 135.

[21] “Soldier Boys, Sergeants Louis Noise and John M’Cann Tell Thrilling Stories of their Great War Experiences,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, September 18, 1918.

[22] “Private Sol Rising: Young Jewish Member of Co. L, who is So Highly Commended for Bravery at Battle of Marne Writes Sister a Letter,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, October 18, 1918.

[23] Snider, Fairfield County In The World War, 135.

[24] “Jewish Sisterhood Meets At Molar Home,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, June 15, 1917.

[25] “Of 1200 Delinquents at Lancaster Only 16 Jews, Welfare Head Notes,” Jewish Independent, August 17, 1928

[26] “Council’s Rapid Growth Continues,” The Reform Advocate 63, no. 1 (1922): 574.

[27] “Grand Social Picnic to be Given by C.J.W. of Lancaster, Ohio,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, August 22, 1924.

[28] Jacob Molar, Oral Histories, The Columbus Jewish Historical Society.

[29] Lisa R. Dill and Dennis E. Miller, Fairfield County Treasures (Lancaster: North End Press, 1988), 68.

[30] “Annual Outing Bose Dovid Church, the Local Jewish Congregation,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, August 04, 1917.

[31] “Feast of Lights Service Held by Congregation of Beth David,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, December 15, 1922.

[32] “Chestnut St. Church May Be Purchased For a Synagogue,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, December 15, 1925.

[33] “Louis Shenker Widely Known In Oil Fields, Dies,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, July 06, 1931.

[34] Obituary of Abraham Shenker, Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, March 02, 1945.

[35] Jacob Molar, Oral Histories, The Columbus Jewish Historical Society.

[36] Obituary of Ben H. Goldberg, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 02 1981.

[37] “Chauncey Soldier’s Body Arrives from Over Seas [sic]”, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 07, 1922.

[38] “Amusements,” Jewish Review and Observer, April 1, 1927.

[39] “Synagogue of Local Jewish Congregation is Dedicated,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, February 28, 1927.

[40] Molar, Morris, “Lancaster Jewry Expresses Appreciation,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, March 4, 1927.

[41] “Church of the Week,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, September 08, 1967.

[42] “Rabbi Shapiro Leaving Lancaster,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, December 08, 1931.

[43] “Ahavas Sholom Elects Rabbi Julius Baker,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 27, 1962.

[44] “Lancaster Jewry to Pay Off Mortgage on Synagogue,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, October 23, 1940.

[45] Obituary of Julius Baker, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, June 12, 1986.

[46] “Lancaster Invites You to Annual Dance Sunday,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, November 3, 1939.

[47] “Hilda Molar Becomes Bride of Joseph Weinthraub at B’nai Israel Synagogue Here,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, August 16, 1926.

[48] “Five Hundred Guests Attend Shenker-Rubin Nuptials Event,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, June 27, 1928.

[49] “Bass Tragedy one of the worst ever seen in Lancaster,” Lancaster Daily Eagle, October 02, 1919

[50] Obituary of Jacob Bass, Lancaster Eagle Gazette, October 21, 1980.

[51] “Lancaster Jewry to Pay Off Mortgage on Synagogue,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, October 23, 1940.

[52] “Killed in Action”, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, March 09, 1945.

[53] Jacob Molar, Oral Histories

[54] Ibid.

[55] “Lt. Abram Commands Coast Guard Mobile Unit,” Lancaster Eagle Gazette, December 28, 1950.

[56] Obituary of Stanton E. Abram, Plain Dealer, April 06, 2011.

[57] Interview with Alan Shatz, Columbus, OH, July 2017.

[58] “Beth [sic] Israel Cong.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, December 10, 1954.

[59] Alan Shatz interview

[60] Obituary of Morris Molar, Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, December 10, 1960.

[61] “Jewish Synagogue is Damaged in Blaze,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, February 5, 1961.

[62] “Lancaster Synagogue is Damaged By Fire,” Logan Daily News, February 6, 1961.

[63] Jacob Molar, Oral Histories.

[64] B’nai Israel Here To Worship in Hall,” Lancaster-Eagle Gazette, February 10, 1961.

[65] Alan Shatz, interview

[66] Howard, Epstein, “Just a Home on the Highway, but It Had a Shabbos Light in the Window,” Cleveland Jewish News, June 24, 1966.

[67] Obituary of Emil Eichel, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, March 14, 1941.

[68] Eileen Beal, “Giving Voice to Small-Town Jews,” Cleveland Jewish News, July 04, 1997.

[69] Obituary of Sam Sharff, Ohio Jewish Chronicle, November 25, 1966.

[70] Obituary of Albert Shatz, Logan Daily News, September 24, 1966.

[71] Alan Shatz, interview

[72] Trista Thurston, “Prosecutor Set to Retire by Year’s End,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, December 18, 2016.

[73] “63rd Consecutive Year of traditional High Holiday Services,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, September 21, 1989.

[74] Jason Maddux, “B’nai Israel closing doors after 67 years,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, August 07, 1993.

[75] Darla Stimer, “Keeping The Faith,” The Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, October 05, 1992.

[76] “Columbus Jewish Foundation Grant Facilitates Religious Education,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, October 21, 2000.

[77] “Couple Wed in June Rites,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, July 24, 1978.