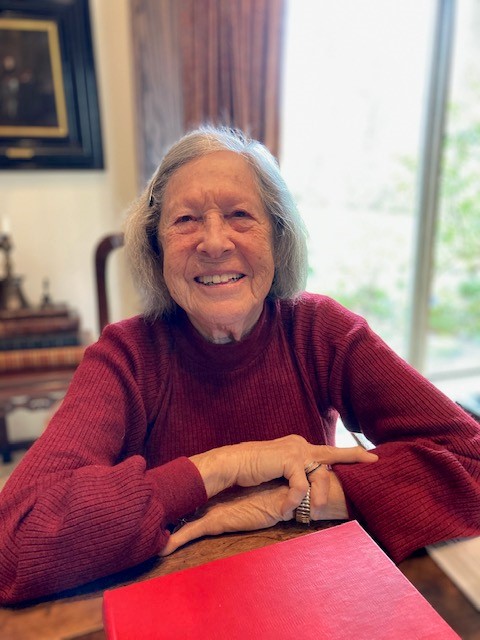

Nancy Lurie Salzman

Interviewer: Nancy Lurie Salzman. That’s who we’re interviewing today for our Oral History Project by the Columbus Jewish Historical Society and I’m Bill Cohen and I’m here with Nancy. Nancy, tell us, first of all, can you trace your ancestors back…

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: …a generation or two or three? What can you tell us?

Salzman: Back to the 18, well, 1850s? My mother’s family came to Dayton, Ohio, after the, actually in 1880s, but my great-grandfather was in the Prussian army during the Franco-American [she corrected herself], Franco-Prussian War, came home on leave because they’d shot his eye and said to his wife, “We are leaving.” And she said, “What do you mean we’re leaving?” He said, “Bismarck is eating up all these little states. He’s going to make a big state and he’s going to be aggressive and every one of us is going to have to serve in armies and my unborn sons,” – and he went on to six, seven, five unborn sons at that time – “are going to have to fight in armies. We’re leaving.” Well, his brother had gone ahead to Dayton, Ohio where there was a huge Jewish community from Germany. Something like 60% of Berlin at that time, which is where they lived, was Jewish and so it was certainly easy and the Midwest was all German. My husband’s…in St. Louis even when he was in medical school, that there’d be people inside at walk-in cafés reading German newspapers so the culture was definitely Midwestern and the architecture was. I can tell you about that because I’m an architectural historian but we won’t go into, we won’t get in to that. Anyway, they all arrived in the 1880’s and I have all the papers from the ship and all that kind of stuff and they came to Dayton, Ohio. That’s my mother’s family.

Interviewer: This was your mother’s…?

Salzman: Family, my mother’s mother.

Interviewer: Your mother’s mother.

Salzman: …who was Rose Israel. That was her name, her maiden name.

Interviewer: …and the person you were just quoting who said ‘We’ve got to get out of here…’

Salzman: Was her father.

Interviewer: Her father. And do you know, his name was…?

Salzman: I will think of it because I have all the family trees. I have everything in writing.

Interviewer: Okay. The 1880s.

Salzman: Around 1883, but they planned, no early 1880s because in the 1870’s he came home on leave, wounded and said, “We’re leaving.” And there was a huge German community. It was nothing, you know it wasn’t going to be that strange and he joined his brother in Dayton, Ohio. My mother went on to Ohio State and joined SDT, met my father who was ZBT because only SDTs would look at ZBTs because that was the German, those were, in Columbus, at Ohio State SDT was the top sorority and, of course, they were all of German extraction.

Interviewer: This was a Jewish German sorority.

Salzman: I won’t, people won’t, if you look at the facts, they will know that it was German. You never hear it said, but if you look at the documentation, that’s, if you look at the names of the people, etcetera, etcetera.

Interviewer: Now what year approximately would this be?

Salzman: She graduated from college in I think, like in 1927 from Ohio State.

Interviewer: Your mother went to college and graduated? That was somewhat unusual.

Salzman: Not in her crowd. No, I mean they filled up the sorority house, so, actually, it was a house then. It wasn’t the one that, although she was on the building committee for the next house. My mother was so active. I tell you. You didn’t need anybody else in America to build America. She was the penultimate, ultimate volunteer. Do you want me to get into that or not? You want me?

Interviewer: Well, let’s talk. Let’s stay in the 1920s which is kind-of your roots because that’s when your mother got…

Salzman: …met my father.

Interviewer: …met your father and so, this happened at Ohio State.

Salzman: Yup, which she loved.

Interviewer: …and she was in a Jewish sorority and he was in a Jewish fraternity.

Salzman: ZBT, which was the top Jewish fraternity. It had mostly people of German origin and there was S A M at Ohio State I’m sure had people who were not of German origin. It was probably more mixed and they were, you know, either Conservative…I don’t know if Orthodox joined fraternities then.

Interviewer: Anyway, you were going to Ohio State but your mother actually was living in Dayton.

Salzman: Came from Dayton.

Interviewer: Came from Dayton. And your father, where did he come from?

Salzman: My grandfather, we don’t know. We have one very interesting anecdote of how he smuggled his brother out of what we think was Lithuania. His name was Lurie which goes way back King David’s sister. I can trace my ancestry. My family, the Lurie family is the oldest documented Jewish family in the world and there’s a book I can show you when we leave.

Interviewer: And you can trace your ancestry back to King David?

Salzman: …‘s sister. My theory is that in the Middle Ages when they didn’t keep written records, they must have all been chief rabbis because those were recorded and I can show you. It’s a book this thick, with its genealogy.

Interviewer: This thick.

Salzman: Anyway, so, my grandfather went to the, his brother was older. He was the child of a second marriage and his older brother was 17 and would be inducted into the czar’s army and they’d never see him again. So, they escaped and they got to the pier which is probably Danzig because that’s where a lot of people from that part of the world emigrated and there was something wrong with his papers. It would take three weeks to correct them and at that time he would have turned the age to be inducted, so the story is, only story he ever told me about his background was that he, somehow, they got a wagon with hay which probably was hay for the horses that were working at the docks. The brother was under the hay. My grandfather was on the little seat with the driver. Somehow, they got past the gate guards, up to the boat and off to America to Sharon, Pennsylvania.

Interviewer: Now hold on. Now approximately what year was this that they got out of Lithuania?

Salzman: Well, I’d have to look at his tombstone but you just have to go backwards and add nine years, you know, you can, we can compute it, I just don’t have it at my fingertips.

Interviewer: This is your grandfather.

Salzman: My father’s father.

Interviewer: Your father’s father.

Salzman: Alright, but, only when my father and his two sisters became high school age, they moved to Columbus because my grandfather wanted them to have an education. Before that, he had little clothing stores in little towns all over Ohio.

Interviewer: Tell us just a little bit about that. What kind of stores?

Salzman: Alright, clothing stores for the…the family story is that someone would come in to his little shop in Mt. Vernon. They sort of settled in Mt. Vernon before he came to Columbus, but before that, whenever, people would come in to the store and say, “Oh, I like that suit in the window.” My grandfather would say, “Yes, it really is fine quality,” da da da da, and the man ‘d say, “Can I try it on?” My grandfather would say, “Oh, it’s the wrong size. I’ll have to take your order and I’ll get the right size,” because it was the only piece of garments that he had in the whole store.

Interviewer: Was what was in the window.

Salzman: …was the front, yeah, because he didn’t have the funds to stock the store. This is a classic story, and so, anyway, they did move to Columbus and…

Interviewer: Now, hold on. Just before we get to Columbus, you had a store in Mt. Vernon. Where else? You said he had some other small stores?

Salzman: Well, he was a peddler. I mean, they sent him, when he went in to Sharon, Pennsylvania, to join the family of the first mother, which is not his mother, I have learned since then, it’s absolutely typical. “Out. You’re not one of us,” and he was sent out into the world, maybe age 13 and they gave him a pack on his back to be a peddler and off he went and I’ve heard this story about many people, and he went from village to village or to farmers’ houses, whatever it was and made his way in the world, literally.

Interviewer: And sold…

Salzman: Pins and needles, and you know, things you could carry.

Interviewer: And this was your grandfather?

Salzman: My grandfather.

Interviewer: Your great grandfather?

Salzman: My grandfather

Interviewer: Your grandfather.

Salzman: …because we know nothing and he never talked about his family ever, so I never got anything. My grandmother, he went to Philadelphia on a buying trip and the family there, they were middle class and they invented. The one was a doctor. One became a lawyer. My grandmother’s siblings. They had invented a certain kind of orthopedic shoe which put them in the middle class firmly because had a factory, made money and they were to, would fix him up with a younger sister and he met Bessie, the oldest. Well, as the oldest of nine, she wanted, I think, she wanted out, so she grabbed my grandfather and off, that was it and they got engaged and came to wherever it was that my grandfather, by then, was settled and because he had a store that he was stocking up in Philadelphia, so anyway, and my mother was very close to that family. Mother and Father, my parents were very close to that Sable family and they ended up in Columbus and they bought a house on Drexel. My father went to East High School. Along came the Flu Epidemic and they shipped him off to Kemper Military School in the middle of Missouri, in Booneville, Missouri, and I have his yearbook and there were a lot of Jewish young students all dressed in military uniform and they had almost 400 students. The head of the Academy was just retired and he’d been in the Civil War, and he avoided the 1917 Flu Epidemic that way.

Interviewer: So, avoided the epidemic by leaving Columbus, Ohio. He wasn’t [home?] schooled.

Salzman: They sent him, my grandfather sent him off to boarding school.

Interviewer: And that was supposed to protect him from the flu.

Salzman: Because you weren’t in an urban kind of setting where there were a lot of people. You were isolated in this little town in Missouri and they were all isolated in their barracks and their bunks and you know, it was a very controlled environment which was safe, and was safe.

Interviewer: And that was a high school, this military academy. So, first he went to East. Then he went to this military academy.

Salzman: I have pictures of all these things, and then to Ohio State, went to Ohio State and then went to law school. I think that’s probably where my mother was because I know she’d say, if they had a fraternity party, she’d say to, “Have you done your homework? Have you finished your homework?” And my father’d say, “Well, I just have this…” and she’d say, “Well, we’ll just finish this before we go to the dance.” And she was very organized.

Interviewer: So, your father, went to law school and his family, he was living as a teenager or in his early twenties and he lived on Drexel did you say?

Salzman: They moved to Drexel Avenue which was then the eastern most street in Columbus and the trolley car, I remember that as a little girl, came all the way, straight down Broad street to that circle that you see at Broad and Drexel, turned around and went back downtown.

Interviewer: So, was that Bexley at that point?

Salzman: It was definitely Bexley. That’s all there was in Bexley, maybe three streets, Columbia, Parkview and Drexel. That was it.

Interviewer: And that would have been in the 1920s.

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: You were born, what year?

Salzman: 1932.

Interviewer: Oh, ’32, and you say you have memories of that.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: So that would have been in the 30s. Okay.

Salzman: For me to visit them. Yeah, to visit them.

Interviewer: So, your parents, they met at Ohio State and they got married what year approximately?

Salzman: 1929.

Interviewer: In 1929.

Salzman: I’m sorry, 1927.

Interviewer: Oh.

Salzman: ’29, because, no, it had to be ’29.

Interviewer: ‘Course, ’29, in late ’29 was the Crash…

Salzman: When was the Crash? The Crash was, oh, then maybe they got married in 1927 because they lived over in East Columbus in a little apartment complex which Nancy or Tom could tell you about and then they said, they decided they would buy a house and they went and they bought the house on Friday before the Crash, so all week, so they, and Friday was the Crash. I believe. October 29th.

Interviewer: Your parents, yeah, something like that, late October of ’29. Your parents bought a house and where was this house located?

Salzman: In Bexley.

Interviewer: In Bexley.

Salzman: 240 South Ardmore, 248 South Ardmore, no, North Ardmore…

Interviewer: 248 North Ardmore.

Salzman: …and the reason they bought that was because the, there was an open piece of land even north of that where there was going to be a school. There may be a school now but let me tell you there was no school while we were there. It was way until after the Depression that they built anything. So, and I have a lot of memories of that house and I had two neighbors. I don’t think anybody else Jewish was in that neighborhood but I would walk to school with them and they, Mother remained friendly with them, with the young women that were, it was Jane Nizely [sp?] and Mary Ann somebody.

Interviewer: Now I just want to make sure we get everything right here. In October of 1929, your parents were living in an apartment,

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: And do you know where that was?

Salzman: I know exactly where that was but I can’t tell you because I don’t know Columbus well enough now to remember but I can find it on a map.

Interviewer: It was in Columbus.

Salzman: It was a right on the eastern part of Columbus.

Interviewer: Near Bexley.

Salzman: Yeah, before the river, before Alum Creek.

Interviewer: Before Alum Creek. In other words, on the Columbus side of Alum Creek.

Salzman: But to make this a very short story. There was the Crash. Had the man cashed the check, the deposit? If he hadn’t, or the payment to buy the house? So, they spent the whole weekend worrying, “Do we own the house or do we not own the house?” because the banks had crashed. Fortunately, the man had gone to the bank. Their money was, and used the money. The man received the money, transferred the property, and they owned the house, but they did not know until Monday when the banks opened again and they could check if they owned it or not.

Interviewer: Wow. So, your parents moved in to this house on North Ardmore…

Salzman: 248 North Ardmore.

Interviewer: …right as the Depression was beginning.

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: And you were born, then in what year?

Salzman: September 22nd, 1932.

Interviewer: You were born about three years later and where did you go to elementary school?

Salzman: Cassingham Road School.

Interviewer: …Cassingham which was south of Broad Street and you were north of Broad Street.

Salzman: Right.

Interviewer: And how did you, did you walk to school?

Salzman: Yes, and I was a very little girl. I had two neighbors who were a little bit older, but finally, finally they moved to 2607 East Broad Street, one house in from the corner of Broad and, it wasn’t Ardmore, and it wasn’t Cassingham. It was the street that’s in between.

Interviewer: Perhaps Stanwood?

Salzman: No. No. Stanwood went this way. It was going this way. I think it could have been Ardmore, because of the mailbox…

Interviewer: Did that put you a little bit closer? Did that put you closer to Cassingham Elementary?

Salzman: A little closer. It was still a big walk. I have two memories of that house. It was a wonderful house but the most historic memory was that Daddy had taken us to the movies on a Saturday, yeah, I do have two memories, and we’re pulling into the driveway in the back. We’re listening to The Great Gildersleeve on the radio and they broke in to say “Pearl Harbor has just been bombed by the Japanese,” and I will never forget that. I couldn’t have been, I was not, I was not ten. I was younger. And as for World War II, they had scrap drives and I remember having an antique iron stove, which I gave them. Well, I now realize the good things that I gave to the scrap drive didn’t go to be melted down for bullets. I’m sure the scrap-drive owner built a very nice business out of what he collected. And we used to play basketball against the garage. It was a double garage at the back of the house, and there was a servant’s quarters above it, a maid’s room with its own heating system, some kind of a gas fire thing that would heat her bedroom and bath and then there was the back stairs and then there was the rest of the house for the, you know, master of the house or however the culture went at that time. We always had a maid.

Interviewer: And so, you were about nine years old when Pearl Harbor happened.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: And what are your memories at Cassingham Elementary School? You were Jewish. First of all, did you have just Jewish friends? Did you have non-Jewish friends? What was it, what were the relations between elementary school kids, Jews and non-Jews? How did they get along?

Salzman: Completely mixed. Completely mixed. Now looking back on it, it was mixed with the Reform Jews. I don’t know. I can’t speak for the ones who belonged to those other temples which we never set foot in.

Interviewer: Your parents were members, your family was a member of what synagogue?

Salzman: Let me tell you about Bryden Road Temple, okay?

Interviewer: Bryden Road Temple.

Salzman: My grandmother’s, my great Aunt Minnie’s, in Dayton, father-in-law founded the Reform Temple in Dayton in 1854. And I remember in 1954, Great Aunt Minnie, they named the Confirmation Class after her because her father-in-law had founded the temple a hundred years earlier.

Interviewer: To celebrate the 100th anniversary.

Salzman: …of the Dayton Reform Temple. So, I have very strong memories. I mean, Temple, well, I think we lit candles on Friday night. I’m not sure. There just weren’t that many customs but we sure, my parents went to temple, I think, every Friday night, and very involved in the temple, and I was very involved in the temple. We had a youth group. We, Rabbi Gup lasted through the War, a very mild-mannered little man, and the minute the war was over, but controlled by the Lazarus family, politically, in the temple.

Interviewer: What was the rabbi’s name again?

Salzman: Rabbi Gup, G-u-p

Interviewer: D-u-p?

Salzman: No, G like in Gabriel.

Interviewer: Okay. G-u-p. He was the rabbi.

Salzman: He was a little tiny man, a very nice wife. Well, his wife, looking back was very modern. She went to work in an airplane, in the airplane Curtis-Wright Factory which was down the road here. That big building that you see at the end of the road was the Curtis-Wright Airplane Factory. We learned to spot airplanes. We were given a piece of paper with all the pictures of the wings so you could identify aircraft, which really wasn’t thinking, I thought that was pretty funny except there was an aircraft [flying through?] there so it might not have been so funny.

Interviewer: The rabbi’s, let me get this straight. The rabbi’s wife worked in the airplane factory…

Salzman: …was Rosie the Riveter. That’s what she did.

Salzman: Well, you can imagine what the congregation thought of that. She went to work as a worker? And, she was, I think, probably socially ostracized, because you just didn’t do this. Well, good for her. She did.

Interviewer: Because this was, as you say, Rosie the Riveter. During World War II…

Salzman: Absolutely.

Interviewer: …when the women were working there in the factories.

Salzman: Yeah, replacing the men. It was a call and she, she took it.

Interviewer: Wow.

Salzman: … but the minute that, the word that I heard after the War, that , which was 1946 so I was just beginning high school, was that the Lazarus family didn’t like him and kicked him out. So, the Lazarus family evidently had a lot of political power. Philanthropically, I don’t think they were such great shakes, but, or were leaders of philanthropy.

Interviewer: So, you’re talking about the Lazarus family who owned Lazarus Department Store.

Salzman: THE Lazarus family. Yeah.

Interviewer: And you say you were very active in the Bryden Road Temple.

Salzman: Well, they, maybe. I don’t think they were much active. They were not more active than anybody else.

Interviewer: Oh, I thought you were saying they were powerful.

Salzman: They were powerful…

Interviewer: Oh.

Salzman: …maybe with the Board of Trustees, I mean, is what I meant, the organization.

Interviewer: Ah, okay. And so, the Bryden Road Temple was on Bryden Road not in Bexley. It was in Columbus.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: And you were members of that, you and your family.

Salzman: Yeah. And we went every, to Sunday School every single week and we went Friday night and it’s kind of funny because there was a series of rabbis and then when I was in high school, Rabbi Folkman came from, originally from Michigan, I think, and he meant well. He had a very big opinion of himself. He said, “You can take notes when I, of my sermons so that when you go off to college, you’ll have term papers you can write from my notes.” Writing down a sermon? A rabbi telling you to write down a sermon in temple was pretty far left. But, anyway, but, he meant, they were lovely people. Minnie’s family, her, his wife, I’ll think of her name. [transcriber’s note: Bessie] She came from Michigan, I think, and she, see, her family comes up again much, much, much, later when I’m in Boston. Anyway, they came from Michigan my junior year in Sunday School, in town. Judah was, because he came from Grand Rapids, Michigan, he rode a bicycle. When you were in junior high school, you didn’t ride a bicycle, but he rode a bicycle, and so I liked, I thought, you know, he was very bright and I liked him as a friend, not as a boyfriend, but as a friend and I would over to his house after school and you’d go down the go down the center steps to his basement and he draped it with sheets and he had, he kept chicken hearts beating and he had a little laboratory and I used to be his laboratory assistant. Well, he said, I’m going to be the youngest professor that Harvard Medical School’s ever seen and indeed, he was. He ended up being that.

Interviewer: Now, wait, I want to make sure I understand. Who was this person?

Salzman: Judah Folkman, the son of the rabbi

Interviewer: Judah Folkman.

Salzman: Very famous.

Interviewer: Yes, he became a fighter against cancer.

Salzman: Just ask him. He’d tell you how important he was.

Interviewer: He was your boy-friend, or friend.

Salzman: Both. Both. He was a good friend and I dated him when, he came, he went to college early. He linked up with Dr. Zollinger at Ohio State. He went to Ohio State. His father bought him a fancy convertible. I think it was lemon yellow, because he didn’t get in to Harvard. He didn’t understand that you had to be, that there were going to be college boards. He was just very naïve and he wasn’t prepared to pass the college boards in the way that he naturally would have, which brings me to another story and I’ll jump through my high school years and all that. In the seventh grade my parents came home with a pile of pamphlets and sat me down and said, “We want to have a talk with you.” THE talk. The Blacks had their talk. The Jewish parents had their talk and we had THE talk and they said, “Your father and I loved Ohio State,” and Mother ran the Fiftieth Reunion. The trees around the Oval Pond were her idea. I mean, she was, there wasn’t an organization in town that she wasn’t effective with and was a model. Sweet person, but I was a latchkey child because she was busy saving America all through the War. I’d come home. She was, she’d be at Union Station passing out coffee and cookies as the troop trains went through. She and Daddy were the USO chaperones for the dances during the War, Saturday nights and, I mean, literally, there was a key under the mat and I let myself in. Also, that house on Broad Street, we had a wonderful Victory Garden which Tom started and I’ve been a gardener ever since, because of that Victory Garden, and we got our vegetables, you know? That’s what you did.

Interviewer: So, you learned to be self-sufficient at an early age.

Salzman: Very.

Interviewer: Your parents sat you down for a talk. What was the talk about?

Salzman: The Talk. The Talk was, “We loved Ohio State. We were Greeks. We were ZBT and SDT,” course the top Reform sorority and fraternity, “and we want you, we had met wonderful people. They are life-long friends. You know them all,” and partly, Mother was always on committees at Ohio State. I think in part because she wanted to get fifty-yard line seats for the football games. Once television came in Mother could stop doing it, but she was always there. “But you’ve got to choose. You’ve got to choose between the Greeks who were wonderful people, wonderful friends or the people who were not Greeks,” not in sororities and fraternities. “You have to choose when you’re on campus. That’s gonna’ be your crowd or this crowd. There are lovely people on both sides. We want you to be with everybody. Therefore, you are going to go East, with a capital E. In order to go East,” which was the Ivy League schools…

Interviewer: So, ‘We’re not going to send you to Ohio State school.’

Salzman: …any state school, “you are going to go to Radcliffe, Wellesley, Bryn Mawr or Mount Holyoke,” you know, “This was our goal for you where you would really find yourself, because there’d be a mixture of people. There wouldn’t be all this sorority and fraternity business and it would be a girls’ school as CSG. So, you’ve got to go to CSG. You’ll do well, probably you’ll do well enough on your college boards to get in to one of the four schools that you decide to apply to but we want you to, this to be safe for you and know that you’re going to get in. The only problem is you go to Columbus School for Girls, 22 kids in your class. They only take two Jewish girls,” because the quota system was still in and I’ve got a great quota system story for you, “but you’ve got a problem. Barbara Schiff, Schiff Shoes which then went to New York, [ ? ] big time, I mean big corporate company. “Barbara Schiff is already there. She’s your age. She went from the fourth grade on. Eve Byers sister is there already. That’s three people. They only have two slots. You’re just going to have to work your head off, seventh and eighth grade, to pass the admissions exam that you took for CSG.” Well, I got in. Eve didn’t. The shit hit the fan in Columbus because my parents had remained very close friends with all their Ohio State friends so, the word got out through the Gentile community everywhere in Ohio that CSG had a quota system. Guess what? Eve got in. They took three girls that year.

Interviewer: Instead of two.

Salzman: Instead of two.

Interviewer: They relaxed the quota.

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: Wow.

Salzman: It was wonderful. The teachers were wonderful. There was only one teacher who was an absolute total bigot – Mary Martha Monica Miller who was a spinster Catholic woman who, the year that I took chemistry and did, used watercolors because I was interested in that and had a gorgeous notebook way miles past anyone else’s. She decided that we didn’t have, wouldn’t have a prize that year for the best notebook and I knew it was because I was Jewish and I was still in high school. I mean, that was probably my first experience with…

Interviewer: So, you entered CSG as what, in…?

Salzman: As a freshman.

Interviewer: As a freshman.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: …and you had to work really hard in seventh and eighth grade…

Salzman: …to pass the admissions exam.

Interviewer: …to get in and then word came out about the quota and they eventually got all three girls.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: So, they had now, now they had three Jewish girls in there.

Salzman: [Related ?] of course, to Temple Israel. That’s the other thing. I mean, we’re not even talking about that yet.

Interviewer: So, so, let me ask you this. What was it like being one of the few Jewish girls at Columbus School for Girls in high school? What was that like?

Salzman: Perfectly normal. We all belonged to Big Junior and Little Junior. Little Junior was freshman/sophomore dances and junior/senior and we all belonged to that. It was…

Interviewer: You all got along.

Salzman: Oh, yeah. I mean, yeah.

Interviewer: Did you have non-Jewish friends and Jewish friends?

Salzman: Absolutely. I didn’t know the difference. They were both. They were friends. Either I knew them from school or I knew them from temple or whatever and I kept up my Jewish things. The temple was very active for our group. We stayed. We had Confirmation Class and then post-Confirmation. The rabbi was smart. We did not need post-Confirmation but the boys, we wanted to be with the boys so, we’d have dances on Friday and Saturday night and then Sunday we’d all rush to temple because we wanted to be with the boys and the boys wanted to be with us. Rabbi Folkman was very with it.

Interviewer: And the Temple at this point was still on Bryden Road or had it moved to…

Salzman: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Interviewer: …the east side?

Salzman: Yes, and don’t let me stop the recording before I tell you about that, at the new temple, because that’s important. Anyway, that was, so that was also our social life, so there was, you know with our non-Jewish friends, but after school, in high school, once the boys could drive, I must say. There was a Jewish crowd with Dick Kohn and a whole bunch of them. They had one or two cars, so they’d pick us up at school which was Parsons Avenue. It was on the corner of Parsons and Oak, not Oak. It’s where this horrible yellow office building is. There was a Greek Revival mansion. It had been turned over into this private school in 1898.

Interviewer: The Jewish boys picked you up near Parsons.

Salzman: My crowd. I must say, my after-school crowd, I think, that was the Jewish boys, because it was Dick Kohn, with a “K,” and I think they were mostly Jewish boys, yeah.

Interviewer: Now why did they pick you up there? What was on Parsons?

Salzman: Our school. School would be out. We had to carpool. There was no public transportation. We were in town. We were at Parsons and, where the Thruway is now.

Interviewer: Near Parsons and Oak, Parsons and Broad.

Salzman: Parsons is parallel to those, isn’t it?

Interviewer: Parsons goes perpendicular to Broad.

Salzman: Alright, well, it was that corner…

Interviewer: Okay but…

Salzman: …but the address was on Parsons. Right. The building faced, which was an old Greek Revival mansion, faced Parsons.

Interviewer: And what was this building?

Salzman: It had been a mansion of the federal judge in about the 1840s. It was part of the Underground Railroad.

Interviewer: But what was it then?

Salzman: It was then the main building for, it’s where CSG started.

Interviewer: Oh!

Salzman: Then they added a wing.

Interviewer: Oh! Now I understand. CSG, Columbus School for Girls, was not where it’s located now.

Salzman: No. No.

Interviewer: Oh, it was in the inner city which was near Parsons. Oh.

Salzman: …which wasn’t inner city in the sense that you would think of inner city today.

Interviewer: Yes. Now, okay you’re telling, okay.

Salzman: And the temple was, you know, over on Bryden Road, not that far. I probably could’ve probably could’ve walked to the temple from there.

Interviewer: Now I understand. CSG was close, was not too far from the Reform synagogue. Okay.

Salzman: Two blocks maybe, not that there were that many members who belonged there, but that had been the center of Columbus back then. Anyway, I get, so then where do I go to college? Where do you want me to…?

Interviewer: Well, let’s see. You were going to tell a story. Dick Kohn and some others picked you up at CSG.

Salzman: Oh, they’d pick us up at school and we’d go out – is there a road, a route called 791 or 571 or something? There was a route out this way and they’d drive us all the way out there and then we’d all pile out of the cars and sort of sit on the side of the road and just talk, chat, you know, interact, so we did see plenty of boys, plus there must have been parties on weekends. There had to be, but I know that, and of course, the country club in summer. Winding Hollow was absolutely where we camped out. We must have gone there every day in high school. I went away to overnight camp. I went to seven different camps all until my last two years they were always, my first three years was a Catholic boys’ school in Maumee, Ohio, because Dr. Piet, our dentist’s daughter had gone there and she had said to my mother, “It’s a wonderful camp.” Sends me to this Catholic camp which is inside this huge dormitory and the counselors were young women whom they thought were going to be novice nuns? No way. The men were overseas in the War. They just wanted jobs for the summer, you know, next to a farm where they had dray horses and hayrides. It was an old-fashioned farm with an old-fashioned couple with a beard, and we’d go for hayrides. So…

Interviewer: There were boys and girls at the camp?

Salzman: No. No. No. No. No. This was just girls, and if we took a nap – we had nap time in a big dormitory – and if we faked that we were asleep, we would get a Catholic prayer card as our reward for going to sleep, but they were very nice, because they had Chapel every day and there were five of us who were either Protestant or Jewish, I think, two Jewish and three Protestant and they let us sit in the ante room. They did not force us to go, but I knew a lot about the Catholic faith.

Interviewer: They did not force you to go to the Catholic religious service.

Salzman: No. No. They were very respectful. It was a very positive experience and I still have pictures of that camp, you know, little kids. So, then I went to a place called Plymouth Shore on Lake Erie which was an awful camp and after that, my parents sent me to a Jewish camp up in Maine to Camp Wenonah. My cousin…

Interviewer: What was the name of that camp?

Salzman: W e n o n a h, and we had Friday night services.

Interviewer: Camp Wenonah.

Salzman: Yeah. Naples, Maine, and my aunt went to the “Rich…” we called the “Rich Girls Camp” which was Triple A, the Rich Girls Camp because they imported sand for the lake, for the beach on the lake. We just went in, but there was a number of Jewish girls’ camps, and actually, my first day at Wellesley I walked in to the dorm and there was a bunkmate of mine from New York City whose family, a very famous art gallery in New York that they had and it was an interesting experience.

Interviewer: So, you had a lot of, you were somewhat active in your synagogue.

Salzman: Very.

Interviewer: You went to Jewish camps.

Salzman: We had a youth group also.

Interviewer: At that point, did women, did girls get bat mitzvahed?

Salzman: Never even heard the word. It wasn’t until I was married, well, we moved. Let me just tell you about the Building Committee and then I’ll jump to my adult, if

Interviewer: Oh?

Salzman: Do you want anything about my adult bat mitzvah?

Interviewer: I want to, oh, yeah, we’ll get there but I want to make sure I understand.

Salzman: …the sequence.

Interviewer: In the 1940s, when you were in your teens…

Salzman: I had mixed friends.

Interviewer: …the idea of a bat mitzvah was foreign.

Salzman: Never heard of it. Ever. I didn’t know what, I didn’t know until I was married and had two children.

Interviewer: You did, though, go to bar mitzvah parties for the boys.

Salzman: No.

Interviewer: Oh?!

Salzman: Boys weren’t bar mitzvahed. I’m talking about boys and girls. We did not have bar mitzvah. We had Confirmation.

Interviewer: The boys did not get bar mitzvahed.

Salzman: No.

Interviewer: You’re talking about the Reform synagogue.

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: And there was something about the Reform movement that said, “We do not want to have our boys bar mitzvahed.”

Salzman: We had, nobody said that. It just wasn’t. Remember the Reformed, it was the Reform Movement, and they, in Germany, and they threw out the old and brought in what they felt was the essence, the significant essence of Judaism and so, all these customs that had grown up in the shtetl and here, there, and everywhere, they’d never been, they’d been, you know.

Interviewer: They got rid of many of these customs.

Salzman: If they were, yeah, back in 1805 sometime. My grandmother’s family, absolutely sure never, you just didn’t think about it. You didn’t learn Hebrew. I never learned Hebrew. I don’t know Hebrew.

Interviewer: Even the boys did not get bar mitzvahed.

Salzman: No, but we had Confirmation, boys and girls. And that was big time, but we were older. We were fourteen and fifteen at it and it was very, very important and family came and we had, you know, from out of town and it was a big deal for the whole community and it was celebrated as a community.

Interviewer: So, in the Reform Movement in Columbus in the 1940s, the Confirmation was THE big thing

Salzman: THE big thing.

Interviewer: Not the bar mitzvah.

Salzman: I was married, had two children, lived in, in West End in Boston and a joint friend was having her son bar mitzvahed and we had neighbors down the street. In fact, her family fled Boston during the Revolution because they were Loyalists, up to Halifax, New Hampshire, Halifax, Nova Scotia. That’s where she was from, but we were all good friends and she asked them to this thing, so she says to me, the Jewish friend, invited us to her son’s thing because I could sit with this friend and explain things to her. I’d never been to one. This was my first bar mitzvah. I was married and had two children.

Interviewer: Before you went to a bar mitzvah. Fascinating.

Salzman: But Confirmation was big. I mean, relatives came from Michigan, came from all over. It was a big deal as a community which is kind of interesting.

Interviewer: And in your Reform synagogue…

Salzman: Temple. Don’t use that word.

Interviewer: You’re right. Temple, the Bryden Road Temple…

Salzman: Yeah. Bryden Road Temple.

Interviewer: There was no, did they use any Hebrew during the service?

Salzman: They had certain prayers: Baruch Ata Adonai Eloheinu Melech haolam…the rest of it, a little bit and it was in the prayerbook. It’s just that it was never used. I have my prayerbooks. I mean, look at those prayerbooks from that period.

Interviewer: So, doing the service mostly in English, that was one of the hallmarks of the Reform Movement.

Salzman: But, you know, you paid attention. You knew what they were saying. You learned. You valued, you developed your values in your family but also from going every week to temple. I don’t think my parents ever missed a Friday night.

Interviewer: You liked the services because they were in English?

Salzman: I had no choice. I mean that’s what, what was was.

Interviewer: That’s what you knew.

Salzman: Yeah. Uhm hum.

Interviewer: So, you graduated from CSG. You went to Wellesley.

Salzman: I got in to all four of my colleges. I got in to Radcliff, Wellesley, Bryn Mawr and then my safety school.

Interviewer: Those are kind of the women’s Ivy League.

Salzman: Exactly. That’s what they aim for in the seventh grade. That’s what those pamphlets were that they brought to show me.

Interviewer: Your parents.

Salzman: Because they wanted, and they knew I could do it. I mean they didn’t just do it for the status or this or that, because you have to be able to handle the work and I was an honor student in college so.

Interviewer: So, what was that, tell me about life at Wellesley as a Jewish woman.

Salzman: That was, first of all, to me it made, it was no different, however there were people who, we did have a Hillel but it was for the Orthodox and they were all from New York City and to me that was a foreign land. I mean, it was, and they, I’ll never forget, the first week I was at school on my birthday it was Rosh Hashanah. We got letters from Rabbi Folkman. It was very [accom..?]. Once we went off to college, he kept close contact with us which was wonderful and we got a letter to go to Temple Israel which was a downtown Reform Temple in Boston and we arrived, up the stairs and ushers wouldn’t let us in because we weren’t members and here, our family was Temple Israel in Boston. Who did they think they were? Made us stand on the steps and later when we joined a temple in Boston, I did not join that temple because I remembered how badly they had treated me as a freshman.

Interviewer: You were turned away as a college student.

Salzman: Turned away until the Kol Nidre, [transcriber’s note: Kol Nidre is Yom Kippur] after the Kol Nidre and we were there in plenty of time. Took three buses to get there.

Interviewer: You felt like an outsider?

Salzman: They treated us like an outsider. I didn’t feel like one, I was treated, I didn’t feel like an outsider. They treated me like an outsider and I still, because I live in Cambridge now, much closer to, I belong to my temple now for sixty-one years in West Newton because the kids went to Sunday School, out in the suburbs where we had lived, but we never lived in Newton. Newton’s the Jewish community. We lived, the first five years when Ed was chief resident, was a resident and then chief resident, we lived, in a little, we bought a house in Watertown, which just sold, and we paid, my father, I’m sure my father bought the house, for 17.5 (seventeen thousand five hundred) just sold for $625,000. How many years later? I mean.

Interviewer: Now, let’s go back to Wellesley.

Salzman: I have to.

Interviewer: What was that like? How many, you were a Jewish woman at Wellesley. What was the Jewish population like? Was it small?

Salzman: That is the story that I have for you. There was a quota system. This is talking about Nineteen…I joined in 1950, okay? Everywhere, all the Ivys, and there are a number of books out, you can read about, one that was written called Making It At Yale Same Story. Just a real, they all had quotas, except MIT and the reason that the post-World War II-transistor-revolution came from Jewish MIT students who could not get in to any Ivy League college. They all went to MIT. I think MIT must have been half Jewish. Serves them right. Anyway…

Interviewer: But you were at Wellesley. What was that like?

Salzman: I was at Wellesley. Ahh, it was wonderful. It was wonderful because, they expected the highest performances you, academically that you could give. They were there for you. It was a beautiful campus, on the lake. I had friends, mixed friends, and you know, religion was, my religious life wasn’t there. I mean, they didn’t have a rabbi. They didn’t have anybody. They had a Hillel but it was really for the Orthodox kids, so, let me, I entered in 1950, Fall of 1950. In 1952, the quota system changed. It was adjudicated, or whatever, everywhere in America, and the schools, Yale, Harvard, you name it, any school that had a quota no longer had the quota system…

Interviewer: Against Jews.

Salzman: Yes, which was fourteen percent. It’s been written about, fourteen percent of the class.

Interviewer: You mean when there was a quota…

Salzman: It was fourteen percent.

Interviewer: …they said, ‘we’ll let Jews in but only up to fourteen percent.’

Salzman: Correct and it was every single school. Well, several things happened. Not at Wellesley, President Pusey, I think it was, of Harvard, went down to Yale and said, “You know you’re going to be a third class college pretty soon because you did not take a single refugee professor at Yale.” I mean, Harvard, they took refugee professors.

Interviewer: Refugees from the War.

Salzman: Before the War, getting them out of Germany…

Interviewer: Oh.

Salzman: …and their families, and supported them. The coffee shop under the spreading chestnut tree that Longfellow made a poem about, was where this place was, and he said, “It’s after the War. It’s science. You have not a single,” I don’t think we had a single Jewish faculty member.” He said, “You’re going to be a third-rate college unless you drop your quota system.”

Interviewer: So, there was a quota system, not just against Jewish students but Jewish professors.

Salzman: In a sense, not a number. It was practice, and, so anyway…

Interviewer: Well, wait. Let me ask you a question here. Before the quotas were dropped, you’re saying the quota was fourteen percent.

Salzman: Fourteen percent. Right.

Interviewer: Now, Jews were only about three percent of the general population.

Salzman: Right, but not of the people applying to top colleges.

Interviewer: But you’re saying even fourteen percent was restrictive.

Salzman: People were turned down. No, I mean you, didn’t take, no Jews no matter how well qualified and if you apply to the Ivy League Schools, you’re pretty well qualified. You know, you’d gone to CSG, in those days, you almost had to. That’s not fair. It helped.

Interviewer: So, the fourteen percent really did have an impact.

Salzman: Oh, yes. I knew, my parents knew that in the seventh grade. That’s why they sent me to CSG. Okay, so, in my junior year which was the first year they had dropped the quota system…

Interviewer: …at Wellesley.

Salzman: Everywhere. I get this call from CJP which is UJA and they say…

Interviewer: United Jewish Appeal.

Salzman: “Would you collect money for us on campus?” Well, I knew you collected money. At Winding Hollow Country Club, if you didn’t give what they thought you should give, you were posted on the bulletin board of the Country Club.

Interviewer: If you didn’t give to the UJA

Salzman: …what they thought you could afford to give you were shamed and I knew this.

Interviewer: So, what happened at Wellesley?

Salzman: So, I get a call from CJP in Boston – Combined Jewish Philanthropies – would I collect money on campus. I said, “Of course,” because to me, you did, right? That was my culture, I mean, I was very naïve. I thought everybody did so, I behaved that way, and they said, I don’t know if I mentioned, maybe it was the house mother or whoever, “You better clear this before you start collecting money on campus for anything.” I have personally this year, given two letters that I’ve saved, signed in ink by the college president saying, “You have my permission, but I think instead of worrying about each doorway, put a box in the entrance to each dorm and let people do what they want,” but they gave me a list of all the Jewish students at Wellesley that they could determine were Jewish, probably from their last name. I don’t know how they knew, or the references because I used a rabbi as a reference. What did I know?

Interviewer: So, wait, so, what’s the significance of that?

Salzman: That was the year that it was no longer fourteen percent.

Interviewer: Could you tell that from the names?

Salzman: Just counting the number of names and the size of the class.

Interviewer: What do you think the percentage went up to?

Salzman: I think it went up to eighteen and then it went up to twenty percent and the year after that, it went up to twenty-two percent.

Interviewer: Wow.

Salzman: And there’s a book called Making It At Yale Same Story and so, I’ve just given, I want one for the archives for the Hillel and I want one for the archives for Wellesley and I just did that this winter. So, anyway, I, just to say that the quota system had dropped and my, Tom, we were talking same story and he gave me the same numbers. He said, he told me fourteen percent because he applied to Harvard, but he was the year where it had dropped and he’ll be the exact same story that I’m telling you. You don’t forget that.

Interviewer: So, you graduated from Wellesley and what happened then?

Salzman: Well, what happened was, that I was dating. In those days, there was, I don’t know if there was birth control or not, but we were, didn’t, we never slept with anybody. I mean if, you were trash if you ever slept with anybody, ever. So, I was dating…

Interviewer: No premarital sex.

Salzman: None.

Interviewer: Because you were scared to get pregnant?

Salzman: No. It just wasn’t, tramps did it

Interviewer: For moral issues.

Salzman: I guess, yeah. I’ll think of a right word. I mean, yes, certainly it was morality. We were moral people. I mean, why wouldn’t you be? So, anyway, at that time, my senior year, the girl in the room next to me wanted to snag the, she was from Anadarko, Oklahoma and was a prodigy, got to Wellesley and was dating this resident at the Mass General Hospital and she was having trouble getting THE ring and she really was beginning to panic because it was senior year and she was leaving.

Interviewer: She wanted to get married.

Salzman: Yes. She wanted this guy to propose to her. So, I said call, and I was, Judah was one of the guys I was dating. Call Judah’s father, the rabbi…

Interviewer: Judah Folkman [transcriber note – Rabbi Jerome Folkman]

Salzman: …and he does marriage counseling. That’s really what Rabbi, what his specialty was, not the Bible or anything academic like that. He did counseling. That’s what his PhD was. He walked down the aisle in his academic robes. Can you believe it? In Temple? Friday night? His doctoral gown? Anyway, called Judah, tell him to call his father in Columbus and ask him, “What do I do?” So, word comes back, “Tell Mary Alice to bake cookies and leave them in Ben’s room. Don’t be there when he finds them.” Well, it worked and she got THE ring.

Interviewer: By baking cookies for her boyfriend…

Salzman: God knows. That worked.

Interviewer: …that helped to tip the balance.

Salzman: It tipped the balance. So, anyway, she said Ben is so grateful, he wants to fix you up with this nice Jewish intern, well, the second Jewish intern ever in the history of the Mass General Hospital in two hundred years and I said, “I don’t want to meet him. I’m dating two guys from the law school, two guys from the medical school and I’ve got to study for my Generals, but I could see Mother on my shoulders saying, “Be nice. Be nice.” So, I said, “Okay, I’ll go out with him.” Well, he was about to go into, he was first in his class at Wash U and then he was the second intern over at the Mass General which was Harvard and he was going in to the Air Force. It was the Korean War and, but they let them, the graduates from medical school have their first year of internship, so he was in over, he was a very decisive person. He was a surgeon. Surgeons are decisive.

Interviewer: And his name was?

Salzman: Ed Salzman.

Interviewer: Ed Salzman.

Salzman: And so, he was not, you know, wasting any time. We had a very nice time. We went out for one hour because he was on the emergency room, thirty-six hours on, twelve off, and in that twelve hours, he drove to Wellesley with the famous, to be famous Judah. I had to take three buses to get to visit the great Judah Folkman. So, we go out to dinner. We go to Howard Johnson’s and there are legs on the table. Pulls out surgical string, puts it in each hand and practices his knots while we’re having coffee.

Interviewer: Your first date…

Salzman: He was practicing knots.

Interviewer: …and he was still worrying about his doctor’s education and his skills.

Salzman: Skills, yeah. Sweetest person that ever drew breath, my husband. Oh! Just… !

Interviewer: That was your very first date.

Salzman: Well, I had my Generals to study for and he kept calling me, but he was going in the Air Force. I mean, so I went out with him. He calls up the two guys from law school and said, “Outa’ my way. I’m leaving. I can’t mess around with her spending her time with you. I’m…” and he called Judah and he called the other guy. It was medical school and the other guy who, thank God, I never married, because three weeks after his beloved wife died, he hooked up with somebody else. I mean, he was…thank Heavens, I never married him.

Interviewer: So, I want to make sure I understand. The man who would later be your husband told…

Salzman: Soon.

Interviewer: …told the other two guys who were interested in you…

Salzman: Four.

Interviewer: …four other guys, he told them, “You go away. This is my woman.”

Salzman: “I don’t have time. I need her anytime she’s…” you know and I had to study for four years-worth of [poli-sci?] courses. It was a prefect marriage. Perfect.

Interviewer: So, when did you get married to him?

Salzman: So, anyway, he came to graduation. He invited himself to one of the events at graduation. My parents had already come. My father sees him walking across the parking lot, very mild mannered, sweet-faced person and said to my mother, “He’s the one.” I don’t know how he knew, but just about his manner that…

Interviewer: Your mother said, “He’s the one.”

Salzman: My father said to my mother, “He’s the one.” So, anyway, I had a job in Boston. He wrote me every single day.

Interviewer: While he was in the Air Force in the War?

Salzman: No, before, he was going down. This is a funny story. I have to do this story. He goes down to Washington, comes back. He says he wanted to give me a pin. I said, “Why?” He said, “Well, you’re going to be an officer’s lady, aren’t you?” I said, “Really?” Well, I know my mother had two fraternity pins from two different guys. That’s another story. I knew the pin didn’t mean that much. Also, I figured out if we were going to get married, it’d be November to have a honeymoon, so, he was going to be in Dayton at Wright-Pat. If I quit my summer job, I was accepted to Harvard graduate school and I was going to go to law school the same class as Ruth Ginsburg Bader, or Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Interviewer: Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Salzman: She and I would have been in the same law school class.

Interviewer: If you had gone to Harvard Law School.

Salzman: ‘Cause I was going to Harvard for graduate school to get the credentials. That’s what I, and my father said, “I’ll support you, for what you want but it’s no place for women. I said, “Don’t worry.” Civil Rights was just beginning. I said, “I’ll find my place,” but then along comes the Korean War and along comes Ed so, that was the end of my law career.

Interviewer: So, Ed and you got married.

Salzman: So, well, wait a minute. Okay. Yeah, so we got married. Okay.

Interviewer: When was that?

Salzman: November 27, 1954 and…

Interviewer: This Korean War was over now? [transcriber note: Korean War June 25, 1950-July 27, 1953]

Salzman: No.

Interviewer: It was still going on?

Salzman: No. No. That’s when he went in.

Interviewer: In ‘54 not ‘52.

Salzman: Yeah. [ ?] ’52 to ’56, probably. He sure went in, unfortunately, but he went to Wright-Pat to ride the human centrifuge, develop the spacesuit, and it was up to 5G’s with no protection. He had early onset Parkinson’s, this surgeon, this brilliant surgeon who was about to be, was on the ladder up, and, which is another, anyway that’s later. That’s what the War did to him. He didn’t go overseas but it was just as bad…

Interviewer: So, he stayed…

Salzman: …but it was in Dayton but Mother was from Dayton and I had all these relatives in Dayton, so we lived in suburban Dayton with family.

Interviewer: And he worked, your husband, your new husband worked at Wright-Pat.

Salzman: …was at Wright Patterson.

Interviewer: And his job was to help develop…

Salzman: …the space, the G-suit. They were breaking the, they were developing aircraft that would break the sound barrier.

Interviewer: And that was just before we started going in to outer space a few years later.

Salzman: But you couldn’t do it if you passed out…

Interviewer: Until they could develop the spacesuit…

Salzman: … they had to keep your blood, you couldn’t let, if the blood drained from your…

Interviewer: …and then you’re saying that he helped develop that and then you’re saying he experienced that, those 5Gs gravitational force…

Salzman: 5G with no protection.

Interviewer: …and that’s, you think, is what…

Salzman: That’s what they think, yeah.

Interviewer: … many years later developing Alzheimer’s. [transcriber note – earlier she said Parkinson’s]

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: Wow. So, you were in Dayton. You were newlyweds.

Salzman: We were in Dayton for two years. I had a job with Cerebral Palsy of Ohio which was just getting started. I’d had a summer job with the lung cancer, lung, I forget what it’s called. It’s got a, that organization, for the summer, so, it kind of already pushing me toward that sort of thing. So, anyway, we were in Dayton and then we came back. Eddy came to the Mass General. He was the second Jewish intern ever at the Mass General. He was the first chief resident in surgery at the Mass General ever.

Interviewer: Jewish?

Salzman: Jewish. Yeah.

Interviewer: And so, you were back now in Boston.

Salzman: And my father, I’m sure my father paid for this wonderful little Cape Cod house in Watertown which has now gone berserk because high tech is expanding in to Watertown and they’re building all these labs and stuff and suddenly, so, that’s Watertown. Okay, so we had, came home from Dayton with a brand-new baby and Ed went off for his on, you know, every other night for five years, and we did not join a temple. I do not know what I did. I really don’t. maybe I got, my parents,’ I don’t know how. I know I went to services. Anyway, so, then at the end of it. They had terrible schools in Watertown. Andy was ready to go in the first grade. Ed stayed on staff at the Mass General which, again, was a landmark thing, and so, we shopped for temples and the temple in West Newton, which is a Jewish community, the wife of the rabbi had gone to Ohio State and so we joined that temple, became close family friends, had seders together, so the kids grew up – my three boys – two and then five years later another boy, and they went through Sunday School. I was involved with the temple. I remember doing nursery school, Purim parties for the little kids and I was on the temple board. Ed was on the temple board. Oh, the story I was going to tell you. Ed walked across the parking lot and my father said, “He’s the one.?” Well, he proposes to me. Well, ya’ gotta’ meet the family. You’re told, you don’t get engaged without meeting the family. Ed’s family was in Springfield, Illinois where Nancy’s from, which is how Tom met Nancy.

Interviewer: Tom and Nancy are, who are they?

Salzman: She’s from Springfield, Illinois, the people who own this house, my brother and his wife.

Interviewer: Your brother and his wife. Okay.

Salzman: Anyway, he goes to Springfield. I hadn’t met his parents. I got engaged to somebody whose parents I’d never met? Well, it turns out, my father was head of the Building Committee for the new temple here, the big temple.

Interviewer: Here in Columbus.

Salzman: Here in Columbus. His father was head of the Building Committee in Springfield, Illinois, so I figured to myself, they must be okay. So, it was definitely a Jewish connection. Meanwhile, people at the Mass General were saying, “I’ve never met anybody Jewish before.” This is the staff and “I think you’re a, I apologize for never getting to know anybody Jewish,” because he was so sweet, and so mild-mannered and so smart and modest that people just loved him. Anybody who knew my husband loved him.

Interviewer: Now this is fascinating because of the Jewish stereotype of Jewish doctors being so prevalent and noticeable and you’re telling me…

Salzman: …in Jewish hospitals.

Interviewer: …that in the 50s and 60s in Massachusetts, in Boston the Jews, at that point, were not prominent.

Salzman: No. No. They were but not at Mass General.

Interviewer: Not at Mass General. Was there something going on there that was…?

Salzman: Yes. It was THE elite. You’ve heard of Bacon Hill and those people? I mean, this was the, this was founded in 1804, 1805. This was THE elite hospital for all of New England, all over America.

Interviewer: So, were there quotas? Is that why the Jews…?

Salzman: They wouldn’t even bother to have quotas. They just didn’t have them.

Interviewer: They just didn’t have Jewish doctors at all…

Salzman: No. No.

Interviewer: Until your husband became one of the very first…

Salzman: Yeah. Yeah.

Interviewer: …in the 1950s.

Salzman: Yeah. Now they’re all Chinese. I mean all my doctors are retired. Every doctor I have is Chinese.

Interviewer: Okay, so you were back in…

Salzman: …back to Bo…

Interviewer: when you first got married you were in Dayton. Then you moved back to Boston, to the Boston area.

Salzman: We moved to Watertown. Then we moved to Westin because four of my classmates were teachers. They said the best schools in Boston are in Westin, and Andy was ready to visit, to start first grade, kindergarten, something like that, so we moved to Westin and bought an old, the oldest big red farm house with a huge barn and my kids got a superb education. We never moved, didn’t, they never were invited to a single, but we joined Temple Shalom, never invited to a single bar mitzvah, ever.

Interviewer: Your children were not invited to any bar mitzvahs.

Salzman: Because at a Reform temple in Newton, everybody had a bar mitzvah but we didn’t live there, and I guess, looking back on it, we wouldn’t be able to reciprocate with “the big party” so my kids, but Confirmation was very important…

Interviewer: Hmm.

Salzman: …because that’s what we did in Columbus, so, I carried my Columbus culture with me to Boston and we did not join Temple Israel [ in Boston] because they’d been so nasty to me.

Interviewer: So, at some point did you come back to the Columbus area or you…?

Salzman: Never.

Interviewer: From then on you were and you still are…

Salzman: And we stayed in Westin until Ed came home and said, you know, and dropped his keys on the, after he had Parkinson’s, dropped his keys on the counter and said, “I was on the ground floor of the garage and a Black woman in a black coat at the far end walked across,” and he said, “I’m not sure I could have put my, if I’d have been closer, if I could have put my foot on the brakes. I could never hurt anybody.” He was, walked across the street to the Peter Bent Brigham and said, “I can’t sign the contract to be Chief of Surgery.” In American surgery, Chief of Surgery at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital becomes the president of the American Surgical. It’s just a straight line and he would have been the first Jewish one probably, and he said, “I can’t be Chief of Surgery here because I want to se…[erve]. My doctor had had a stroke at the Mass General. I never saw him operate. That was wrong and I can’t do that to my doctors, my patients here, my residents.”

Interviewer: You’re saying he was worried about his own ability at that point?

Salzman: He wasn’t the best. No, he wasn’t going to operate. He wasn’t going to touch a knife.

Interviewer: Because…

Salzman: He had no idea, because he had Parkinson’s.

Interviewer: He realized that he was compromised.

Salzman: That’s the word and would become…he wasn’t really then, he could have, but he wasn’t going to hurt anybody.

Interviewer: But how many years was he a doctor in Massachusetts?

Salzman: Well, he managed until he, well, also he had a lab. He discovered. He was interested in blood-clotting and he was a world, when he entered the field, we had a Sabbatical in England.

Interviewer: But approximately how long was his career?

Salzman: That’s what I’m trying to figure. We went there in 1958, and there were eight people in the world that did research in blood-clotting, and he was given this year in England to go all over Europe and visit each lab for each person, so, he was at the beginning of, and still take aspirin, until he became more and more compromised and then he was, and he jogged every day and he tripped, hit his head and that was, he said, “That’s it. I’m finished. I’m…,” you know, and unfortunately, our son was dying of a cancer so the two of them over the four-year period…

Interviewer: Your son was dying of cancer.

Salzman: Yeah. When was that?

Salzman: …in Washington, same period, 1954, no 1984 to ’88 or ‘89 or something like that.

Interviewer: In the 1980s.

Salzman: Whenever. When did Ed die? No, 2011. They both died a month apart in 2011.

Interviewer: Ah. About ten, twelve years ago.

Salzman: They had four or five years of, both were bed-ridden mostly, but, we came back from this year in England. We took the Sabbatical, because he gave up surgery and he wanted to recycle himself into a full-time lab, although he had a lab but he was recycling into it. He wanted to study with this one person. We come back and Ed says, “It’s your turn,” he said. “These years, you raised the boys, you…you know it’s your turn,” and the youngest, two were off at Yale and the other was just entering high school, ‘cause he was five years younger, and so, it turned out, it was a perfect time. I was 53, I think, something like that, and well, the year in England, I love old buildings. Well, I just feasted in England with the nineteenth, mid to late nineteenth-century architects, because I was surrounded by them and I came back and Ed said, “It’s your turn. You know, you raised the kids, you raised me. It’s your turn and I will do anything I can for you to have your time now.” Well, now they’re doing it in reverse. People are giving up their careers at age 53 and finding what I had before age 53, which I find an interesting phenomenon around here, everywhere. My rabbis are retiring, recycling because they did their thing. Well, I was starting to do my thing. So, it turned out that Boston University and two other places on the east coast were the only places in America where teaching historic preservation – the Historic Preservation Act had just passed two years before. So, I, took, my first course was an evening course, and I’ll never forget. Ed picked me up for the, was to pick me up for the, his lab party because he had a huge lab, for Christmas and we were giving our talks, because it was Fall semester. And I picked up the phone and said, “Ed. It’s going to run late. Just wait. Wait.” Well, this kept happening and happening. Finally, he picked me up and I said, “Well, it’s obvious, I can’t do this going to graduate school, because…” He said, “Nonsense.” He said, “We’ll buy a microwave oven and we’ll take separate cars,” And so I was one of the first persons in historic preservation, nationally, one of the first students.

Interviewer: In the 1980’s.

Salzman: 1980s, yeah, and I made a brilliant career until Ed started to take to his bed and I thought, “No. I can’t leave him.” They said, “You can get a carrel at the Widener Library, ‘cause we lived in Harvard, now. We moved to Cambridge. We finally moved to Cambridge because there was a shuttle bus to the medical school and he could get them, to work. And, “You know? You can get a carrel, you know? Put your books there.” I couldn’t leave him and I’ve never regretted it.

Interviewer: Taking care of him in his last…

Salzman: And I could still do writing and research but not on the professional level that I would have done and I’ve never regretted it because he came first.

Interviewer: But you were, you were starting to launch a career…

Salzman: I had launched it. I had launched it.

Interviewer: As a historic preservation…

Salzman: And I was a writing and doing research, and, you know, I wrote books. I mean, I really did all kinds of things. I did, I was asked to [tap ?] the historic preserv… the history of Boston University buildings and, at that point, they had a thousand, one thousand, because it was all adaptive reuse and you know, I was head of organizations, I mean, the professional organization, you know, I had a career, but not as important as my husband. Just not. But let me, you want me back in Columbus? What are you looking for?

Interviewer: Well, I just wondered, so, after you moved, after you were married and you settled down in Dayton and then you moved to Boston.

Salzman: Yeah.

Interviewer: Obviously you have relatives here in Columbus but you never came back to Columbus?

Salzman: I visited.

Interviewer: Just to visit. Okay, but you have a lot of…

Salzman: Yeah, but the rabbi’s wife had gone to Ohio State so we always had this little thing going.

Interviewer: And you have many fond memories of your life in Columbus.

Salzman: Oh, yeah and you know, I go to reunions, too, and I see my classmates. I see my CSG classmates every five years, and last year, there are very few of us left, Eleanor Vorys and I went to reunion even though it wasn’t our reunion year and we made a big deal of it. We were the oldest back, you know, and I watch CSG change and grow and I’ve not been shy about giving them advice every so often.

Interviewer: You know, you mentioned that you got in to CSG as the barriers were being relaxed a little bit. The quotas were being relaxed. Now, here we are in 2023 and CSG and, I think, it’s safe to say, even the Columbus Academy, are much more diverse than they were…

Salzman: Oh…

Interviewer: …seventy, sixty years ago.

Salzman: …absolutely, yeah, yeah, but it was a feeder school for me. I mean, probably for some of my classmates, it was a fancy school. They were fancy. They wanted a fancy school, you know.

Interviewer: You called it a feeder school because it fed you into Wellesley?

Salzman: Into Ivy League schools, yes.

Interviewer: Yes.

Salzman: And I’ve always loved it, you know, and I was a very good scholar. I knew how to study. I knew how to research. I knew, and I enjoyed it.

Interviewer: You know, I didn’t ask you yet about any memories you might have of Jewish institutions such as the Jewish Center or…

Salzman: There wasn’t one.

Interviewer: There was not. Was there the Schoenthal Center?

Salzman: I don’t know.

Interviewer: Hmm. Okay. So, you didn’t go…

Salzman: No. I don’t think so. Or maybe there was for people but not for the Reform group.

Interviewer: Not…boy, tell me about this. Your, one of your themes is that the Reform Jews were isolated or…

Salzman: No.

Interviewer: …were insular or what? Tell me.

Salzman: Insular, they were world unto themselves, and, I think, probably the Orthodox and the Conservative. However, Bernie Yenkin’s father believed that all Jews were Jews and he, they belonged, and Bernie belonged and Sandy who was my very close friend in Boston. In fact, we fixed her up with her husband on a blind date. He was a doctor. Each was a world unto itself. The Conservative had their world. The Orthodox had their world, and we had our world. I never set foot in, this thing called the [Tabernale ?]… Club, something? [transcriber note: Excelsior Club?] Tommy could tell you the name of it. They had their little country club over near the railroad tracks in Bexley.

Interviewer: Oh.

Salzman: I never set foot in it.

Interviewer: Now, you did talk about, did you talk earlier about Winding Hollow?

Salzman: Winding Hollow. My father in college, when in Law School, they came to him. They knew he was going to settle in Columbus and they said, “You’re going to settle in Columbus. We’re going to start a golf club. Do you want to help us start it?” So, he put his name down and probably, I don’t know what he could have contributed. He was just a student.

Interviewer: And that became Winding Hollow.

Salzman: Yeah, and that’s where we lived. That’s where I was married. That’s where we spent our summer-times outside of camp. We hung out there and we flirted with the boys at that end of the pool.

Interviewer: You have a photograph there. Is that you?

Salzman: That’s me flirting, posing.

Interviewer: …and you’re on a [?].

Salzman: I mean you don’t just sit like that.

Interviewer: Yes, you’re posing. Yes, you’re very flirtatious.

Salzman: I think, in Junior High School.

Interviewer: Now Winding, explain, Winding Hollow had to be created because the Jews were not allowed in other country clubs?

Salzman: No. Oh, yes. Oh, absolutely.

Interviewer: That’s true.

Salzman: The only time I ever got into them was if classmates had a dinner or something at Columbus Club or Rocky Fork. I’ve been inside them maybe twice in my life.

Interviewer: Rocky Fork and the Columbus Country Club, those were off limits to Jews?

Salzman: Absolutely.

Interviewer: And how did you, did that, as a teenager, how did that information get to you?

Salzman: What was, was. You just knew.

Interviewer: And that was just accepted that that was the way things were.

Salzman: But you didn’t need them because you had your own.

Interviewer: Ah. Okay.

Salzman: You know, although, Big, Big-Little-Junior-Sophomore-Freshman-High-School-Dance-Club and that was very important. It’s where we learned to, you know, ballroom dancing. We sat on, the boys sat on one side, the girls, and you’d ring a bell and you’d stand up and you’d learn to waltz or whatever, but you did that, and I…

Interviewer: Was that mixed? Was that Jews and non-Jews?

Salzman: I just don’t know.

Interviewer: Did you go to that?

Salzman: Oh, you bet.

Interviewer: Okay, well, at least it was, at least that was open to Jews.

Salzman: Well, I went to CSG so, I don’t know which was which.

Interviewer: Oh.

Salzman: But it certainly made it open doors. Yeah.

Interviewer: Now how about Martin’s Kosher Foods?

Salzman: Never heard of it.

Interviewer: Never heard of it. Okay.

Salzman: I didn’t even know ko… I wouldn’t know what kosher food was. I do have one other ethnic memory. When I was a really little girl, Mother had to go to the open, downtown open market…

Interviewer: Oh, yes.

Salzman: …and she’d sometimes leave me in the car. Sometimes I’d go with her and she was, I must say. She’d point out that these people were not our type, that they were from Hungary, or they were from, you know, they were a different, their families came from a different place, more recently.

Interviewer: They were Jewish.

Salzman: Jewish.

Interviewer: But they were still different from you because…

Salzman: More recently, these are the people and, I think, names like Schottenstein and whatever that, that would be that category.

Interviewer: And so, you knew you were Jewish and these other people were Jewish,

Salzman: A different kind of Jewish.

Interviewer: But your mother was telling you they were different people.

Salzman: Yes.

Interviewer: You were German, you had German background and they were Hungary…

Salzman: Yes, but Mother was, I would never have thought Mother was a bigot. That’s how she was brought up. ‘This is who I am. This is my identity,’ and she passed on her identity.

Interviewer: But she had a different view of different Jews.

Salzman: Well, she was, she lived. She was more mature, but her sorority certainly had no, nobody who was Orthodox, ever had a hint of Orthodox. I’m sure SDT didn’t. I’m sure they were all Reform. It’s just the way it was.

Interviewer: How ‘bout the Excelsior Club? Was that around?

Salzman: Yes, maybe that’s what the [Tabernale ?] Club turned into. I never set foot in it. I…

Interviewer: That was on Cassady near the railroad tracks.

Salzman: Okay. Yes. That used to be the [Tavern Ale?] Club. Yes. I think maybe once I walked through it but some of the guys that I would meet after school belonged to that. It was a more mixed thing after school or they had, they were in both camps, had one foot in one camp, one foot in the other camp. They were passing. Nobody ever used the word but that’s what it was.

Interviewer: Now there were these, in high school, there were these Jewish quasi fraternities and sororities, AZA, Emma Kauffman,

Salzman: Uhn-uhn. Never, would never have, never bothered with that. Never. First of all, I never heard of Emma Kaufman, but no. No.

Interviewer: You didn’t belong to that.

Salzman: No. It was another world.

Interviewer: Okay.

Salzman: I mean, what did we know? These were our friends. These were the children of our friends. My mother belonged to Meanie Cats which was a group of women that started…

Interviewer: What was it called?

Salzman: The Meanie Cats. Oh, you’ve got to, that is great history. You’ve got to have that in your files.

Interviewer: Minnie Cats?