A History of Jewish Life in the Upper Miami Valley

By Austin Reid

Dedicated to the members of Congregation Anshe Emeth who have kept the light of Judaism

burning in the Upper Miami Valley for over 150 years. Austin Reid, August, 2021.

Introduction: The First Jewish Families in the Upper Miami Valley

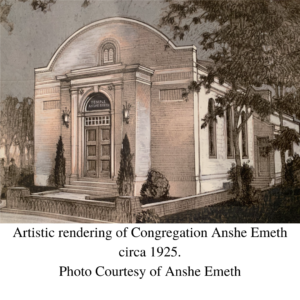

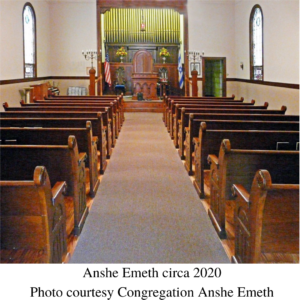

Situated between two homes along Caldwell Street in Piqua is Congregation Anshe

Emeth, the center of Ohio’s fourth-oldest organized Jewish community. While the current tan

two-story brick building housing Anshe Emeth dates to 1922, the group was organized over sixty

years prior on March 7, 1858.[1] For over 150 years, Jews have been represented among the

religious communities of the Upper Miami Valley. The story of Jewish life in the area, however,

does not begin with the creation of Anshe Emeth. Rather, Jews are known to have lived in Piqua

and Troy since the 1840s and it is likely that Jews were among the itinerant traders passing

through the area during the 1830s. Jews and other ethnic and religious groups came to Miami

County in increased numbers after the Miami & Erie Canal was extended north of Dayton in

1837. This canal connected Miami County to Cincinnati, Ohio’s largest city during the 1800s,

and enabled business people from the city and others living along the Ohio River to quickly

reach Miami and surrounding counties. Cincinnati at the time was also home to Ohio’s largest

Jewish community and its oldest Jewish institutions. Most, if not all, of Miami County’s earliest

Jewish residents spent time in Cincinnati before moving north.

Emma and Moses Friedlich are the first Jewish family known to have lived in Piqua. The

couple arrived in town in 1849 when Piqua’s population was around 3,200. Emma and Moses

were, like many American Jews at the time, immigrants from Bavaria; they were married in 1841

after their arrival in the United States.[2] After settling in Piqua, Moses opened a clothing store on

Main Street, which he managed until his retirement in 1891. He also was involved in the creation

of Citizens National Bank in 1865 and served as a director and vice president of the bank from

1870 until his death in 1892.[3] Emma and Moses raised at least three children, Caroline, Jacob,

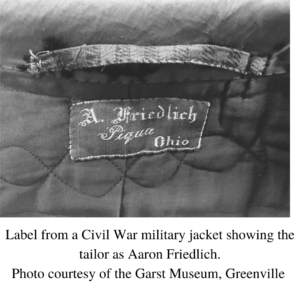

and Tillie. The husband and wife were not the first members of the Friedlich family to reside in

Piqua. In 1846 Moses’ brother, Aaron arrived in town and found work as a tailor. Around 1850

Aaron married Theresa and the couple had ten children, five sons, and five daughters. These

children would eventually move to various places, including Bowling Green, Cleveland, Iowa,

Rochester, and Wapakoneta. Aaron and Theresa, however, lived in Piqua for the remainder of

their lives and they made several contributions to their adopted city. Most notably, Aaron served

for a number of years as a member of the local Board of Education and was president of Piqua’s

Social Club.[4] Emma, Moses, Aaron and Theresa are all commemorated on the stained glass

windows found in Anshe Emeth today.

Eight miles south of Piqua in Troy, a Jewish presence

Eight miles south of Piqua in Troy, a Jewish presence

was also growing by the 1840s. Levi and Nancy Barnett

along with Jenny and Joseph Wertheimer are the first

Jews known to have lived in town. Both couples arrived

in the 1840s and both Levi and Joseph supported their

families by selling clothing. During the mid to late

1800s, the clothing business, which was rapidly growing

due to technological advances in sewing, represented a

major economic area for recent immigrants. Jews in

America, who were primarily born in Central Europe or

second-generation Americans, were particularly likely to become involved

in the clothing business because of anti-immigrant or anti-Jewish sentiment in other trades and a tradition in many families

of operating small businesses in Europe. Family connections also allowed many newer immigrants to enter the

clothing business. As an example, it was not uncommon for a brother to emigrate to the United

States and send money back to pay for the voyage of his other siblings after establishing a stable

business. These siblings would work for their brother upon arriving in America and sometimes

go on to create their own stores in new towns.

In Troy as in Piqua, Jews involved themselves in communal activities. Levi was a

member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal organization, and one of the

Barnett children, Jacob, would become a member of the local Elks lodge.[5] Organizations such as

the Elks and Odd Fellows filled an important need within 19th-century communities. In an era

before Social Security and other social welfare programs, communal societies such as these

served not only social purposes, but also as a type of insurance providing medical care and

disability benefits for members. Fraternal societies would also provide funds to cover at least

some of the burial costs for members and they helped to support any orphans left behind by the

deceased. Some Jews also affiliated themselves with religious and social institutions in larger

cities to maintain connections with the wider Jewish community. The oldest Jewish organization

in the Miami Valley, Temple Israel traces its origins to 1850 when twelve Jews gathered in

Dayton to form a Hebrew Society. This Society was dedicated to organizing religious services

and creating a set burial ground for Jews.[6] The Society’s early members included individuals in

the Friedlich family. In 1852 Gelinde Friedlich was buried at the Rubicon Cemetery in Dayton,

which had been organized by Society members as the region’s first Jewish cemetery in 1851. At

the time of her death, Gelinde was just seven years old.[7] Jews in Piqua, Greenville, Sidney, and

Troy also traveled to larger cities to maintain social ties with other Jews. The foremost Jewish

fraternal organization was known as B’nai B’rith and in 1864 a lodge was formed in Dayton.

Known as the Eschol Lodge, the organization is the ancestor of the B’nai B’rith Youth

Organization, which continues to exist in Dayton into the 21st century. Over the years, many

Jews from Darke, Miami and Shelby counties would affiliate themselves as members of the

lodge. Not until 1944 would a B’nai B’rith lodge be formed in the Upper Miami Valley.[8]

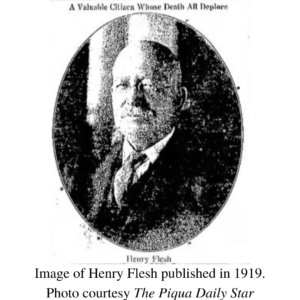

During the 1850s, more Jews arrived in Piqua and Troy. These included Henry Flesh,

Herz Landauer, Abraham Lebensburger, Charles Lebolt and Esther Lebolt, David and Regina

Louis, Barbara Schwab, and Abraham and Fannie Wendel. It is also during this same decade that

the first Jewish residents of Greenville were recorded. These residents included Charles and Julia

Bachman, Henrietta and Simon Bachman, Moses Huhn, and Joseph Oppenheimer. Henry Flesh,

who was born in Ellingen, Bavaria, immigrated to the United States in 1852 at the age of 15 or

16. In 1856 he moved to Troy from Dayton and in 1858 he relocated to Piqua. Once in Piqua,

Henry found work with Aaron Friedlich selling clothing. He remained with Aaron until 1862

when he decided to go into business for himself. Henry’s business and civic interests expanded

and by the 1880s he was among Piqua’s most notable citizens. More on this will be written later.

Hertz Landauer and Abraham Wendel came to Piqua as peddlers. Hertz met Barbara Schwab

after settling in Piqua and the two married but did not have any children.[9] Barbara may have

been related to Solomon Schwab, who is listed in The Israelite, a Jewish newspaper out of

Cincinnati, as a Piqua resident and the fiancé of Bertha Hessberg of Cincinnati in 1861. No other

records of Solomon’s time in Piqua were located. More information, however, exists regarding

Abraham Wendel.

Abraham was born in Prussia in 1821 and came to the United States in 1848. By 1852 he

made his way to Piqua where he met Fannie Friedlich, the sister of Aaron and Moses. The couple

wed shortly after and seven children were born from the union.[10] In 1856 Abraham saved enough

money to put aside the peddler’s pack and open a jewelry store on Main Street. One son, Jacob

remained in Piqua as an adult to carry on the business. Another child of Abraham and Fannie

died in infancy and, Samuel, the youngest son died at the age of 22. All four of the Wendel

daughters moved out of Piqua after their marriages. Bertha and Sadie moved to Portland,

Oregon, while Helen and Rose married men living in Cincinnati. Helen moved to Greenville

with her husband, Abraham Simon by 1900. Abraham would become a notable cattle and wool

merchant in Darke County.[11]Both Abraham and Fannie are commemorated on the stained glass

windows of Anshe Emeth.

Abraham Lebensburger, Charles Lebolt, and David Louis all owned businesses in Piqua

by 1860. Abraham was involved in the local clothing trade from 1858 until 1883, when he

moved to Chicago with his wife, Caroline. Abraham was also the brother-in-law of both Charles

and David. Charles married Esther Lebensburger in 1854, three years after his arrival in Piqua.

At the time, Esther lived in Dayton. Interestingly, Charles and Esther had grown up only a few

miles from each other in Bavaria and they reunited after immigrating to the United States.[12]The

husband and wife were married for over 50 years and they had ten children. These children

would mostly move to either Springfield, Missouri or Springfield, Ohio. David married Regina

Lebensburger in the late 1850s and the couple had at least four children. In addition to sharing

family ties, both Charles and David were involved in the grocery business. The two men also

shared similar community activities as members of B’nai B’rith, United Ancient Order of Druids

and Odd Fellows.

Greenville’s earliest Jewish residents shared many traits with their coreligionists in Piqua

and Troy. The Bachmans, Moses Huhn, and Joseph Oppenheimer were all immigrants from

German-speaking regions of Europe and all spent at least some time in the clothing business

once in Greenville. It is of note that the presence of German-Jewish immigrants in the Upper

Miami Valley by the mid-19th century was part of a larger national pattern. Between the years

1820 and 1880, an estimated 150,000 Jews would arrive in the United States from predominantly

German-speaking regions of Europe. Jews, however, comprised but a small part of the

approximately three million German-speaking immigrants in total who came to the United States

during the same period.[13] Most German-speaking lands would become part of the modern

German state when it was created in 1871. During the decades preceding this event, however,

much of Central Europe was beset by revolutions and other forms of political and economic

turmoil. In 1848, revolutions became especially widespread throughout Europe ushering in an

exceptionally large wave of immigration. Central European Jews, who were often subjected to

violence and discriminatory laws that limited their economic opportunities and ability to marry,

faced additional incentives to emigrate.

Some German-Jewish immigrants to the United States became wealthy. One such

immigrant was Simon Bachman. By the time of his death in 1907, Simon achieved success in

business through his clothing store on Broadway Street. For a number of years, Simon also

operated a saloon on East Main Street named the Lion Garden.[14] This business took its name

from the Lion Brewery in Cincinnati. Simon’s life, however, had its sorrows. Of the 12 children

born to Simon and Henrietta, only four were living when Simon died.[15] Henrietta Rosenbush

married Simon in 1854, and the couple remained together for over 50 years. At the time of

Henrietta’s death in 1912, she was one of Greenville’s oldest residents having reached the age of

82.[16] The Greenville Democrat referred to Henrietta as a “pioneer lady” in her obituary and

remarked, “being exemplary Jews never interfered with the [Bachman] family mingling with all

other denominational people.[17]” While intended as a laudatory statement, the paper’s comment

also reveals a certain bias that viewed many Jews as holding themselves at a distance from the

larger community due to their faith. This belief was not reflected in Greenville or the hundreds of

other cities and towns in which American Jews lived by the early 20th century.

Charles Bachman, who was likely a brother of Simon, founded the Bachman’s Boss

Clothing House on Broadway in 1859. For a time he also owned a store named the Elephant

Clothing Company. He and his wife, Julia had at least four children. Joseph Oppenheimer lived

in Greenville by 1852 and he operated the California Clothing Store on Broadway. In 1853 the

Oppenheimer store was renamed the People’s Clothing Store and it operated under this name

until at least 1859. It is also of note that Joseph, along with dozens of other locals, helped to

finance the construction of the Greenville Palestine turnpike in 1856.[18] By 1866, Joseph sold his

clothing store to Moses Huhn. Moses lived in Greenville since 1858 and his first job in town was

working at F. & J. Waring’s dry goods store. Moses was also active in the community as treasurer

of the Volunteer Fire Company and as a member of the Masons and Odd Fellows.[1] It does not

appear that Moses ever married. Following his death in 1897, Morris, a nephew of Moses, took

over the clothing business. The example of People’s Clothing Store demonstrates how some

Jewish-owned businesses were passed along to other Jews, who could be either relatives or

connections from the wider Jewish community, by older owners. Other businesses would follow

similar paths in later years.

A Place to Gather: The Establishment of Congregation Anshe Emeth

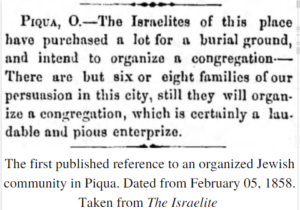

By the late 1850s, Piqua’s approximately eight Jewish families were sufficiently

organized to establish a formal society for religious study and worship. This organization, Anshe

Emeth, was created on March 7, 1858, and its name

Emeth, was created on March 7, 1858, and its name

translates to People of Truth.[20] From its earliest years,

Anshe Emeth also drew Jews from surrounding areas

such as Greenville and Troy to its services, which were

initially conducted once a month and on certain

religious holidays at the home of Moses Friedlich.[21]

Within a year the members of Anshe Emeth relocated

to a rented hall found at 200 North Main where the congregation

remained until 1875. The first officers of the congregation were,

Moses Friedlich, President, Aaron Friedlich,Treasurer, and Moritz Friedman, Secretary.[22] Moritz,

who does not appear to have lived in Piqua for long, operated a clothing business out of the

Masonic Building alongside a man named August Frickman. While modest in size, Anshe Emeth did

not escape notice from larger Jewish communities in Ohio. Rather, even in its infancy Anshe

Emeth was cited by The Israelite as setting an example of dedication and piety for Jews in other

small towns to emulate.[23] In 1859Abraham Wendel replaced Aaron Friedlich as treasurer.

Abraham, who was a skilled scholar of Hebrew, also served as a lay leader for the congregation until

his death in 1894.[24]

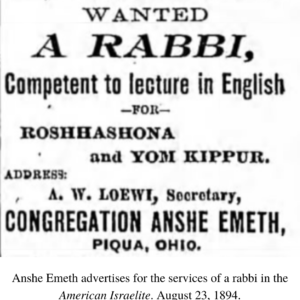

Ordained rabbis occasionally visited Anshe Emeth to speak or lead major holiday

services. On July 4, 1860, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati, who was the foremost

American rabbi of the time, visited the congregation to deliver a lecture. Reflecting on his visit to

Piqua a few days later Rabbi Wise wrote:

Our brethren [in Piqua] are few in number, about seven families, still they united

themselves two years ago into a congregation, bought land for a burial ground, furnished

a room for a temporary synagogue, where they meet once a month for divine worship…

People in those county places live much happier and more content in their quiet places

then we do in our noisy cities with all our opulence, luxury, refinements, and studied

gratification of our passions.[25]

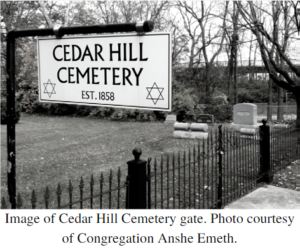

The burial ground referenced by Rabbi Wise is Cedar Hill Cemetery, which is now located along

Scott Drive in Piqua. At the time of the cemetery’s establishment in 1858, however, the area was not built up. Cedar Hill is the final resting place, not only of many Jewish families from Piqua, but also individuals from nearby towns including Lima, which did not have its own Jewish cemetery until 1917.[26] In September 1859, Abraham Levi became one of the first people to be buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery. It is possible that Abraham Leviwas a clothing merchant from Greenville since a businessman by this name was advertising in the local Darke County Democrat by 1857. No advertisements for Abraham are found, however,after 1858.

In addition to maintaining a rented hall and burial ground, the early members of Anshe

Emeth also organized to support various charitable causes both locally and internationally. In

1860 the congregation raised $50 to benefit Jews in Morocco who were suffering from

persecution.[27] At the time, $50 would have the same purchasing power as approximately $1,600

in 2021. In 1866, Congregation Anshe Emeth sent $25 to benefit impoverished Jews living in

Palestine.[28] These two collections demonstrate that, while Piqua was still a modest-sized town of

approximately 5,000 people, its Jewish residents saw themselves as connected with the wider

Jewish world and were familiar with events far beyond the Upper Miami Valley. This same

outlook was shared by non-Jews living in the area who were also connecting with far-flung

communities through new technologies such as the telegraph, which first came to Piqua in 1850.

Piqua’s first railroad line, which came through town in 1858, also spurred news and additional

population growth.[29]

The April 12, 1861, attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, profoundly

affected life in the Upper Miami Valley. Within a short time, many local men joined the Union

Army and other residents found additional ways to support the war effort. In October 1862, the

110th Regiment was organized at Camp Piqua. While it is not known if any Jews served in the

local regiment, two Jews who moved to Piqua in the years following the Civil War, Moses Flesh

and David Urbansky, are known to have served in the Union Army. Moses Flesh, who was the

brother of Henry Flesh, served in the 23rd Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. This regiment saw

action at Port Gibson, Champion Hill, the Siege of Vicksburg, and other places.[30] Moses was

wounded during the war, and, after relocating to Piqua, he became active in the local Elks lodge

and Grand Army of the Republic post.[31] He was also a member of Anshe Emeth and was one of

five people to sign the congregation’s revised articles of incorporation in 1924. Moses, who was

known by many as “Uncle Mose”, also played Santa Claus for many years at the Kaoop

Children’s Home during the Christmas season.[32]

David Urbansky lived in Columbus, Ohio, at the time of the war’s outbreak, and, like

Moses, he was a recent immigrant from Central Europe.[33] Six months after the attack on Fort

Sumter, David enlisted with the 48th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, which saw action at the Battle of

Shiloh, Siege of Corinth, Vicksburg, and several other locations. In recognition of his bravery at

the Battle of Shiloh, David was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Thirteen months

later in Vicksburg David was again commended for his actions after he braved enemy fire to

rescue an officer who had been wounded.[34] Only 17 other Ohioans received the Medal of Honor

during the war and only five other Jews in the Union Army were recognized in this way.[35]

Following the war, David obtained his American citizenship and moved to Piqua with his new

wife, Rachel. The couple had 12 children and David ran a successful clothing store. At the time

of David’s death in 1897, he was buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery and his widow soon moved to

Cincinnati. Several of the Urbansky children also relocated to Cincinnati, and when Rachel died

in 1914 her husband’s body was removed from Cedar Hill for reburial at Walnut Hills Cemetery.

A Period of Growth: Jewish Arrivals in the Upper Miami Valley in the Late 19th Century

By 1875 the number of Anshe Emeth members had grown to 12 adults, and the

congregation relocated to a new building on West High Street at the northwest corner of Public

Square. This building, which was owned by Aaron Friedlich, was three stories tall and the

congregation met inside one of the upper halls.[36] It was also in this same year that Congregation

Anshe Emeth was first incorporated with the State of Ohio.[37] Newer Jewish residents in the

Upper Miami Valley around this time included Julia and Samuel Epstein, Jeanette and Louis

Hebel, Marcus Lebensburger and Meyer Newhoff. Julia and Samuel lived in Greenville while the

Hebels, Marcus and Meyer resided in Piqua. All of these individuals were involved in some

aspect of the clothing business. Samuel Epstein owned part of Bachman’s in the late 1870s and

for a time he was a business associate of Charles Bachman. In 1874, he ran a branch of Charles’

Elephant Clothing Store in Versailles.[38] Louis Hebel was associated with the Bee Hive [sic]

clothing store. This shop appears to have been an early example of a chain store since other Bee

Hive clothing establishments existed across Ohio by the late 1800s. Marcus and Meyer did

business together at a clothing shop on North Main Street. During the late 1870s, the Jewish

population of the Upper Miami Valley appears to have remained fairly homogenous in terms of

ancestry and religious belief. Most, if not all, Jews in the area were recent immigrants from

German-speaking areas of Europe or the children of these immigrants. Almost everyone also

practiced the more liberal form of Judaism taught at the recently established Hebrew Union

College in Cincinnati.

This teaching, which was known as Reform Judaism, emphasized Judaism’s ethical

precepts over religious laws and sought to make Jewish practice more compatible with the

realities of life in the United States. Liturgical changes advocated by many Reform Jews during

the late 1800s included mixed seating in synagogues, the introduction of organs and other

instruments into religious services, and the abolition of head coverings during services.

Congregation Anshe Emeth was among the pioneers of Reform Judaism in America. In 1873 the

congregation became a charter member of the newly organized Union of American Hebrew

Congregations. This organization, now known as the Union for Reform Judaism, continues to

exist well into the 21st century and Anshe Emeth has maintained its membership. Anshe Emeth

was also among the first congregations to host visiting student rabbis from Hebrew Union

College, a tradition that continues as of 2021. Most

religious Jews living in the United States in 1880 believed

Reform Judaism to be the future of American Judaism.

Back in Europe, however, events in the Russian Empire

were about to usher in the largest wave of Jewish

immigration to the Americas yet seen. These immigrants

would change the course of American Jewish cultural and

religious life. Some eventually found their way to the

Upper Miami Valley, where they would contribute

significantly to Jewish history in the area.

Beginning in 1881, increased violence against Jews began to occur in many areas of

Eastern Europe due to political turmoil combined with longstanding prejudices. This violence

sometimes took the form of organized riots which became known as pogroms. Many Jews were

killed during these violent outbursts and thousands of families were made homeless. Violence,

compounded by oppressive laws, eventually compelled over two million Jews to immigrate to

the United States by 1924. While more wanted to leave Europe after 1924, the Johnson-Reed

Act, which was passed by Congress to limit further immigration from eastern and southern

Europe, caused a sharp decline in the number of new Jewish immigrants. Relations between the

new Eastern European Jewish immigrants and the older, more established German-American

Jews were not always cordial. Much of the disagreement was caused by differences in religious

practice and economic status. Specifically, Eastern European Jews tended to practice Orthodox

Judaism and most were also poor. Some native-born Jews in the United States feared that the

religious conservatism of Eastern European Jews and their impoverished state would lead to an

increase in anti-Jewish sentiment locally. In an effort to avert this, Jewish organizations such as

B’nai B’rith and Hebrew Union College sought to provide some forms of financial relief and

education services to Eastern European Jews, but these efforts were often seen as paternalistic by

the immigrant communities.

One letter published in the American Israelite by Abraham Herzstam, a clothing

merchant in Sidney, Ohio, in 1909 touches on some aspects of the interactions between Reform

and more orthodox Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

If these pessimists [i.e. opponents of Reform Judaism] were here to see the many

beautiful temples, the interior decorations and furnishings, the families seated together,

hatless large congregations, hear the fine music and singing during services, they would

be astounded – feel as if they were in a dream. They would then know what useless

apprehensions they had, how erroneously they predicted. There are plenty of crude and

queer ways left and more continually coming from abroad; many ways and actions are as

conspicuous as the uniforms of the police, which must be eliminated for our mutual good.

A nice, bright, intelligent looking young man (lately from Russia, now residing in

Toledo, O.) passed through here recently buying old clothes. I said to him “You appear to

have good talent; why not try for a scholarship in the Hebrew Union College? That would

surely better your condition.” He replied: “I was offered the opportunity, but my father

objected, saying he would prefer to see me in the grave than to have me enter this

“Goyim college”. Is such ignorance bliss?[39]

Abraham was an immigrant from Baden, which is located in what is now southwestern

Germany, and he lived in Sidney since the late 1870s. During the 1880s and 1890s, most new

Jewish families arriving in the Upper Miami Valley continued to come from German-Jewish,

Reform backgrounds. These families included Harmon and Sarah Bornstein, Betty and Gus

Felheim, and Herman and Julia Sternberger. Both Harmon and Gus owned businesses in

Greenville. Harmon managed Bornstein’s Barrel House, a liquor store located at the back of

Kipp’s Drug Store on Public Square. In 1886, Harmon sold the store to Max Ostheimer of

Cincinnati, who may also have been Jewish. Gus, who was a member of the Masons for 48

years, was associated with the Cincinnati Cheap Store, which sold dry goods.[40] In 1887 Gus sold

his store to John Martin and Frank Gorden and went into the clothing business.[41] He also

developed interests in the tobacco business. Sixteen years later the Felheim family moved to

Cincinnati. Herman Sternberger, who was a resident of Piqua by 1883, co-owned a music hall in

town and he was involved in other properties.[42] These real estate interests included a mattress

factory on West Water Street and a portion of Fountain Park and the Forest Hotel.[43] Herman was

also active in the Democratic Party and he served as an elector for the State of Ohio in the 1892

presidential campaign.[44] Julia Sternberger was the daughter of Isaac and Regina Horkheimer,

who were connected with the Jewish community in Wheeling, West Virginia. By 1897, Julia and

her husband relocated to that city.

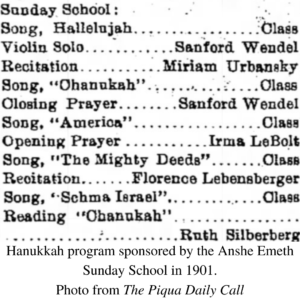

Due to the continued growth of the Jewish community in the Upper Miami Valley, a Sunday School was

established by the members of Anshe Emeth by 1880. In this same year, the

Union of American Hebrew Congregations estimated that 20

students were enrolled in the school and that Piqua’s overall

adult Jewish population stood at 26.[45] It is likely, based on

activity at other Ohio congregations, that the ladies of Anshe

Emeth took a leading role in organizing the Sunday School.

No record of a formal Jewish women’s organization in the

area exists, however, until 1901 when a chapter of the Council

of Jewish Women, a national organization, was formed in

Piqua.[46]46 The group, which met monthly, was composed of 21

women in its first year, and it was formed with the help of supporters from Cincinnati.[47] Caroline

Flesh, the wife of Henry Flesh, served as the group’s first president, and Irma Louis, the wife of

Abraham Louis, was elected as the first vice president. The executive board was completed by

Flora Wendel, who served as treasurer, and Nannie LeBolt, the first secretary. Other members

included Isabelle Lazaron, Rose Louis, Rita Marks, Bernice Silberberg, Minnie Silberberg,

Bertha Urbansky, and Esther Urbansky. Council members helped to raise funds for the Jewish

Consumptive Relief Society in Denver, which built a hospital to treat patients from all

backgrounds, and supported other charitable causes.

Around 1882 members of Anshe Emeth began to organize weekly Shabbat services in

Piqua. Never before had Jewish religious services been held so frequently in the Upper Miami

Valley. In 1893, Anshe Emeth moved its location once again. The congregation was now

operating out of a rented hall located at 266 West High Street above Beck’s Commercial

College.[48]Anshe Emeth remained here until 1923 when the synagogue on Caldwell Street was

constructed. Young Jewish adults in Piqua were also finding ways to connect with each other,

and with other Jews from surrounding towns. Among the social events organized in the 1880s

were dances that drew guests from various communities, including Bellefontaine, Delaware, and

Springfield.[49]49 Individuals from small towns outside the Miami Valley were also affiliated with

Anshe Emeth. During the mid-1880s, it is known that some Jewish families from Delaware

traveled around 75 miles one way to attend holiday services at Anshe Emeth.[50] This not only

demonstrates the challenges Jews in that community underwent to attend public religious

services on holidays, but also the rarity of synagogues in the wider region. It should be noted,

however, that Jews in Springfield formed a religious community in 1866.[51] Construction on

Lima’s first synagogue, however, did not begin until 1914.[52]

Among those who contributed to the development of communal, economic and Jewish

religious life in the Upper Miami Valley by the 1880s were the children of the earliest Jewish

residents of the region. One of the most notable households was the Flesh family. In 1863 Henry

Flesh married Caroline Friedlich, the eldest daughter of Emma and Moses Friedlich, and the

couple had at least three children. Their names were Leo, William, and Joel. While William

eventually moved to New York, Leo and Joel remained in Piqua and entered into various

business interests associated with their father. As mentioned previously, Henry Flesh began his

time in Piqua as a clothing merchant, and his store became well known throughout Miami

County. By the late 1860s, Henry’s business interests had expanded to include banking and

furniture manufacturing. For over 50 years, Henry was involved with Citizens National Bank.

This involvement included serving as the bank’s president for many years.[53] Henry was also

associated with the Border City Building and Loan Association, which was established in Piqua

in 1882.[54] He would serve as this company’s president for over 30 years. Henry’s role in local

furniture manufacturing stemmed from his work with the Cron-Kills Company, which he also

served as president for several years. Leo followed his father into the clothing and banking

business and eventually, he too would serve as president of Citizens National Bank.[55] Leo was

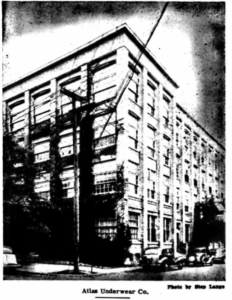

also the president of the Atlas Underwear Company from 1900 to 1928. Atlas, which was

founded in 1899 as the Piqua Underwear Company, would grow to become one of Miami

County’s largest employers by the mid-20th century. Its plant, located at the corner of Downing

and Rundle Avenue, was the largest in the world devoted

and Rundle Avenue, was the largest in the world devoted

exclusively to the manufacture of union suits.[56] Joel went into the

furniture manufacturing business and served as vice president of

Cron-Kills.[57]

Members of the Flesh family were also involved in a variety of

civic and community organizations. Caroline Flesh was active in

an interfaith organization known as the Associated Charities,

which held its first meeting in 1904. At the meetings, she

represented Anshe Emeth.[58] Henry served on Piqua’s City

Council for 25 years and for part of this time was the body’s

president.[59] Henry also served terms as president and treasurer

of the Piqua Board of Trade, a precursor to the contemporary

Chamber of Commerce, secretary of Anshe Emeth and master of the local Masonic lodge.

Additionally, among the projects Henry worked on were creating the Piqua-Troy rail line, helping

to bring electricity to Piqua and organizing the Piqua ElectricCompany, and establishing the Piqua

Memorial Hospital, which opened in 1905.[60] Leo and Joel Flesh

Flesh

were active in various community organizations,

including the Elks and Masons. Leo was also a supporter of

public education. This interest was expressed most notably

through his support of the Schmidlapp Free School Library,

which was renamed the Flesh Public Library in 1931

following a major donation by Leo.

While most of the Lebolt children moved away from Piqua

shortly after reaching adulthood, one son, Meyer, remained in

town long enough to have a family of his own. Meyer, who was also

known as May, was married to Rebecca Lebolt and the couple had

at least two children, Alice and Irma. Both daughters were students at the Anshe Emeth Sunday School.

Like his father, Charles, Meyer was involved in the grocery business and he may have operated the same

business on  College Street. In 1907, however, Meyer sold the

College Street. In 1907, however, Meyer sold the

grocery store to Calvin McCracken and the family seems to have

left Miami County soon after. Two years later, Rebecca died and

was buried at Cedar Hill. During Meyer’s time in Piqua, he served

terms as president of the Retail Merchants Protective Association

and as Nobel Grand of the Odd Fellows.[61]

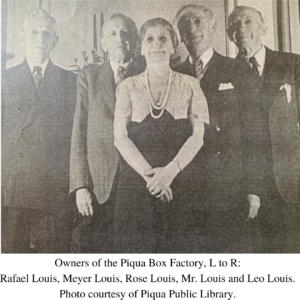

David and Regina Louis had five children, Abraham, Leo, Meyer,

Raphael, and Rose. Abraham married Irma Volmer of Cincinnati in 1898,

and, around this same time, he managed a clothing store named Flesh & Louis,

alongside Leo Flesh. It is also of note that Irma’s brother, Leon, who was a rabbi

in Charleston, West Virginia, occasionally visited Piqua to see family and

conduct services at Anshe Emeth. In 1910 Irma died, and Abraham eventually

moved to NewYork City where he represented the Atlas Underwear Company in business dealings. Leo

followed his father into the grocery business and eventually associated his store with the national

chain, Piggly-Wiggly.[62] He also expanded his business to Sidney. Leo was married to Blanche

Wallbrunn, who was an active leader in the local Jewish community. Meyer and Raphael were

the oldest children of David and Regina and the two brothers partnered in business for much of

their lives. Early in their working years, the brothers owned a jewelry store, and later they

formed the Louis Metal and Iron Company, which sold scrap metals.[63] Their most notable

business achievement, however, came in 1908 when Meyer and Raphael established the Piqua

Paper Box Company, which continues to exist well

Paper Box Company, which continues to exist well

into the 21st century.[64]

Before moving into the 20th century, it is worth

noting that a number of Jewish families in Auglaize

County had personal or professional ties to members

of Piqua’s Jewish community during the late

19th-century. While located outside the Miami

Valley, these ties to Piqua merit mention. By the

mid-1870s Lena and Sol Bamberger were living in St

Marys with their children. It is likely that the family

was supported by a clothing business. Twenty years

later, another member of the Bamberger family, Herman,

who may have been a brother of Sol, lived in Greenville with

his wife Matilda and their six children. Around this same time, Sol was active in creating a telephone

company in St Marys.[65] Most of the Bambergers appear to have left St Marys by 1910, but one,

Louis Bamberger, remained until at least the late 1920s. Louis was the son of Lena and Sol and he

was married to Elsie Spier, a native of Connecticut. In addition to serving as president of the local

Retail Merchants Association, Louis was also active with the Ohio Retail Clothiers and Furnishers Association.[66]

To the east of St Marys in Wapakoneta lived Moses and Rosa Hirsch, Abraham and Rose

Kahn, Frederika and Nathan Kusel, and Adolph and Henrietta Steinberg. Moses and Rosa lived

in Wapakoneta with their son, David, by 1880. The family was supported by Moses’ work as a

clothier. Abraham Kahn was an immigrant from Alsace who came to the United States in 1869.

Shortly after he arrived in Wapakoneta, where he was likely met by relatives, including a

sister-in-law named Sarah Kahn. Abraham at first worked as a dry goods merchant and later

began a manufacturing business that produced farm tools and handles.[67] In 1888, Abraham

married Rose Friedlich, a daughter of Aaron and Theresa, at a ceremony held at Friedlich home

in Piqua. Rabbi Mayer Messing of the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation officiated. Frederika

and Nathan lived in Wapakoneta by the late 1870s and the couple supported their family through

Nathan’s work as a cattle dealer. Nathan’s life was cut short, however, in 1883 after he was

struck by a train. Following Nathan’s death, Frederika worked to support her five children.

Frederika died seven years after her husband and her two youngest children, Leon and Albert,

went to live at the Jewish Orphan Asylum in Cleveland.[68] Adolph and Henrietta, who were both

immigrants from Central Europe, were wed in 1867 and they made their first home together in

New Bremen, Ohio.[69] Here Adolph operated a clothing business and later sold produce. The

couple also had six children. In 1893 the family moved to Wapakoneta, where Adolph opened a

hotel by 1900.[70] While Wapakoneta’s Jewish population was never more than a handful of

families, more Jews would find their way to the town in the early 20th century.

Growing Visibility: Jewish Life in the Upper Miami Valley During the Early 20th Century

Around 1900 it was estimated that Piqua’s Jewish families numbered approximately 12.[71]

While Piqua’s Jewish community did not exceed more than 1 percent of the city’s overall

population, it was nonetheless the largest Jewish community in the Upper Miami Valley and it

held a visible presence in the overall community. Local newspapers, including The Piqua Daily

Call, regularly ran articles on the various Jewish holidays and carried news about Jewish

communities in other parts of the United States and abroad. The reporting found within local

newspapers, however, was not always accurate. For example, on September 12, 1901, The Piqua

Daily Call carried an article highlighting the observance of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New

Year. In it the author remarked, “…the ram’s horn or ‘shofar’ is sounded as significant of the

throwing off of Pharaoh’s power from over Israel and the Lord’s ‘deliverance of his chosen

people’ from their bondage and slavery.”[72] This explanation of the shofar was not correct. The

shofar in ancient times was used to announce the arrival of various religious holidays and the

beginning of a new king’s reign. Its use has been preserved in Jewish communities during the

month leading up to Rosh Hashanah and on the holiday itself to alert attendees at religious

services of the importance of the time and of sincere repentance. The Piqua Daily Call’s error

was remarked on by the editors of The Hebrew Standard in New York City, who included it

along with erroneous quotes about Rosh Hashanah from other national papers.[73]

This story illustrates that while Judaism was regarded as an important piece of the faith

community in the Upper Miami Valley, the more detailed aspects of the faith and its rituals were

not always understood by non-Jews. In addition to marking the annual observance of Rosh

Hashanah, another holiday tradition maintained by the members of Anshe Emeth was conducting

confirmation exercises on Shavuot for the graduates of the congregation’s Sunday School.

Unlike blowing the shofar, however, the practice of confirming young Jews had modern origins

stemming from the Reform movement. The adoption of a confirmation ritual represents how

some Jewish communities took certain Christian customs and rituals and incorporated them into

Judaic religious life. Shavuot is itself an ancient biblical holiday that developed originally to

mark the harvest time in Israel. In later centuries after the exile of Jews from Israel, the holiday

also came to celebrate the anniversary of the Torah being received by the Israelites at Mt. Sinai.

It is for this reason that many Reform communities selected Shavuot as the day to confirm young

Jews. Confirmation classes at Anshe Emeth were of modest size. For example, in 1911 five

young people were confirmed by the congregation.[74]

Adult religious education was not neglected by members of Anshe Emeth. By 1902 some

Jewish women in Piqua were meeting for weekly Bible study.[75] Around this same time, the

members of the Council of Jewish Women reorganized themselves as the Jewish Ladies’ Aid

Society. This women’s group sponsored social activities to raise funds for charity and organized

a weekly “Thimble Social” in member’s homes where needed items were created for local

charities.[76] Over the years, these charities included the Jewish Infant’s Home in Cleveland, Piqua

Memorial Hospital, and the Red Cross. Caroline Flesh hosted the first recorded Thimble Social

at her home in February 1903 and these socials continued into the 1930s. The Ladies’ Aid

Society also supported the Anshe Emeth Sunday School and sponsored public lectures on Jewish

history and theology. The Society’s educational work included raising funds to purchase books

on Jewish subjects for Piqua’s public library. By 1913 the Society had 15 or 16 members and it

formally joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods in this same year.[77]

Between the years 1895 and 1917 several new Jewish families arrived in the Upper

Miami Valley. It is also likely that these years represented the peak time for Jewish immigration

to the region. New Jewish families in Piqua included the surnames Dagan, Kastner, Katz, Marks

Mickler, Ostertag, Shuchat, and Yassenoff. Fannie and Solomon Dagan arrived in Piqua by 1910.

Both were immigrants from Europe, and like many Jewish immigrants to the United States at the

time their family was supported through Solomon’s work in the scrap metal industry. Solomon’s

business, Ohio Scrap Iron and Metal Company, was located at 651 West Water Street. By 1914,

Solomon’s business had earned the family enough money that Solomon was able to own a piece

of real estate on Main Street. This property was rented to Fannie’s brother, Harry Mickler, who

co-founded the Mickler Department Store around 1914 with his brother, John. Harry had moved

to Piqua by 1907 with his parents, Abram and Celia, and two younger brothers, Edward and

Moses. At the time, Abram and his children operated Mickler & Sons, a clothing store located at

326 North Main. In 1917, John moved to Springfield, Ohio, with his new wife, Sarah, who was a

previous resident of Lexington, Kentucky.[78] Eventually, the other Mickler brothers would also

depart from Piqua.

Joseph and Sara Kastner lived in Piqua by 1917, and Joseph supported his growing

family through his work selling scrap metal. Joseph’s business was named the St. Louis Iron and

Metal Company and it was originally located along Covington Avenue. By 1920, Joseph was

joined by his brother, Samuel, and the business informally became known as Kastner Brothers.

Joseph and Samuel were immigrants from Ukraine while Sara was born in London, England.

Joseph and Sara were wed in 1914. By this time, Sara lived in Xenia, Ohio.[79] Joseph, Sara, and

Samuel were all active members of the Piqua community, and Joseph was posthumously

inducted into the Piqua Civic Hall of Fame.[80] Joseph and Sara supported the Red Cross and

Y.M.C.A., and Samuel, together with his wife Dina, was active with the Red Cross and

Inter-Church Council. Like the Kastner brothers, Samuel and Milton Katz were siblings who

moved to Piqua with their wives, Alma and Florence, to grow a business. This business was the

Katz Brothers Clothing Store, and it was

opened in April 1910.[81] Both brothers,

however, left Piqua with their wives by 1920.

Louis Marks, Bert Ostertag, and Louis

Ostertag were also contemporary clothing

merchants in Piqua. The Ostertag Brothers

firm, founded in 1895, would remain a fixture

on Main Street for 47 years.[82]

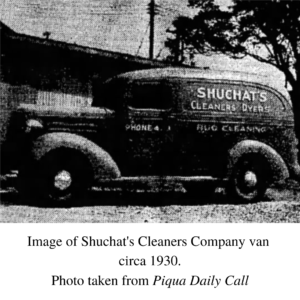

When Israel Charles Shuchat moved

to Piqua with his wife Dora in 1914 to open a

dry cleaning business, it represented one of

the first enterprises of its kind in the city.

Shuchat’s remained in business for over 60

years, and it would become one of the largest dry cleaning operations in the county. Charles and

Dora had three children, Joseph, Samuel and Trina. Joseph went on to become a podiatrist, or

foot doctor, in Piqua for over 55 years, while Samuel carried on the family tradition of dry

cleaning. At first, Samuel worked in Piqua and later he oversaw the relocation of the family

business to Sidney, where it was known as One Hour Cleaners. Shortly after graduating from

Piqua High School, Trina moved to Chicago. It is of note that descendants of Charles and Dora

continue to work in Sidney and their business, Clean All Services, employs

around 280 people.[83]

The last Jewish couple in Piqua which will be discussed in this section is Carrie and Isaac

Yassenoff. While the Yassenoffs did not remain in Piqua for very long, one of their sons, Leo,

went on to become a notable philanthropist within the Columbus Jewish community, and this

connection to Columbus merits mention. Carrie and Isaac settled in Piqua by 1895, and Isaac

found work selling hides, pelts, and scrap metals. While Carrie was an immigrant from

southwest Germany, Isaac was born in Ukraine. It is likely that Isaac was among the first Eastern

European Jews to live in Piqua. The Yassenoffs had at least three children, Leo, Rebecca, and

Solomon, and all were born in Piqua. Around 1912 the family relocated to Columbus. Leo would

become quite wealthy through his role as co-founder of the F & Y Construction Company, which

began business in 1919.[84]

Sidney and Troy were also home to recent Jewish immigrant families during this same

time period. In Sidney lived David and Louis Halverstein. These men, who were likely brothers,

worked in the clothing business. Some sources also spell their surname Halberstein. By the

mid-1930s, David moved to St Marys with his wife, Molly, while Louis remained in Sidney with

Rosa, his wife.[84] One son of David and Molly, Joseph, went on to write for the Lima News as a

sports journalist. Another son, Marvin, also went into journalism. Twenty miles south of Sidney

in Tory there lived Jacob Stayman. Jacob arrived from Dayton in 1913, and prior to Dayton, he

lived in Russia, where a wife and children still resided.[86] Jacob found work in Troy as a scrap

metal trader, and, following World War I, he was joined in town by his sons, Philip and Samuel,

and a daughter, Helen. His first wife, however, died in Europe during the war.

On March 25, 1913, the Miami Valley was visited by one of the worst floods on record.

Piqua was hit particularly hard, and at least 38 residents died.[87] The deluge was part of a larger

series of flooding disasters that struck Ohio that same year. Among the organizations that

mobilized to provide relief for flood victims was the Ladies’ Aid Society.[88] Four years later, the

lives of many residents of the Upper Miami Valley were again uprooted due to the onset of

World War I, which the United States entered on April 6, 1917. Among the locals who entered

the service were at least three Jews. Their names were David Halverstein, Samuel Louis, and

Moses Mickler. It is also of note that two sons of Leo Flesh, Alfred and George, served during

the war, but they did not practice Judaism. Leo’s wife, Gertrude, was a Christian and the Flesh

children were raised in that faith. Leo, however, maintained a connection to the Jewish

community throughout his life. When Leo was buried in 1944 both Christian and Jewish funeral

rites were used.[89] Efforts were also made on the home front to support the war effort, and Jews

contributed to both local and national activities. Fannie Louis and Leo Louis were active with the

local Red Cross, while Leo Flesh lent his efforts to the textile division of the Council for

National Defense. Members of the Jewish community also came together in 1916 to raise funds

to support refugees in Europe and Palestine.[90]

During or immediately after World War I a few new Jewish families arrived in Piqua.

These families included the Funderburgs and Polaskys. In 1917, Kline and Stella Funderburg

relocated to Piqua after Kline took a position as the manager of the Peoples Credit Clothing

Company. This clothing store was part of a chain headquartered in Dayton, and the Funderburg

family remained in Piqua until 1935 when Kline took a position with headquarters.[91] Harry and

Rebecca Polasky arrived in Piqua by 1919. At first, Harry found work as a tailor, and later he

opened a clothing store on North Wayne Street. Both new and old families helped to ensure the

continuation of Jewish communal life in the Upper Miami Valley during the 1910s. Throughout

this period, Emanuel Kahn served as rabbi of Anshe Emeth. It was not a rabbinic post, however,

that brought Emanuel to Piqua. Emanuel, who was also known as Manuel, was born in

Cincinnati and graduated from Hebrew Union College. Prior to relocating to Piqua in 1910, he

lived in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he served at Temple Emanu-El.[92] Manuel was married to

Freda, an immigrant from Germany whose father, Jacob Wolf, and brother, Simon Wolf, both

lived in Miami County during the 1900s. Jacob and Samuel moved to Piqua around 1903 and

they operated a clothing store formerly owned by Meyer Newhoff. When Jacob retired and

Samuel moved away, the business passed to Manuel. Now named E. Kahn & Company, the

business would remain a fixture on North Main Street for several decades.

A Synagogue on Caldwell Street: The Dedication of Congregation Anshe Emeth

On April 2, 1923, Congregation Anshe Emeth was dedicated at 320 Caldwell Street.

Approximately 250 people, including many non-Jews, were estimated to have attended the

ceremonies. At the time Piqua was home to around 25 Jewish families.[93] Other members of the

congregation came from Greenville, Sidney and Troy. It was reported by The Piqua Daily Call

that Miami County was home to the smallest Jewish community in the United States to build a

synagogue.[94] Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg of Dayton was an ardent supporter of Anshe Emeth

during the fundraising campaign for the new synagogue. He also officiated at the cornerstone

laying ceremony for the synagogue in 1922, which was open to the public. Remarking on the

event, Rabbi Mayerberg wrote in the Ohio Jewish Chronicle:

Piqua is an inspiration. The erection of a new house of worship in that small community

is an inspiration to all Jews. There are only a few Jews in Piqua… Our co-religionists of

that small community are therefore to be congratulated upon their achievement… One

may wonder how so few people can accomplish so much. The answer is simple.

Co-operation, unity, and harmony among the people have made their dreams of a house

of worship a reality.[95]

Rabbi Mayerberg’s insight into the members of Anshe Emeth stemmed from his

ministerial work in Piqua, which began at least a few years before the building of the new

synagogue. He visited Miami County monthly to teach adult Bible classes and met with students

at the weekly Sunday School. Jewish religious services were held every Friday evening and on

Sundays twice a month. All this activity led Mayerberg in one letter published in August 1922 to

describe Anshe Emeth as “a model small town congregation.”[96] It should also be noted that

Rabbi Sidney Tedesche of Springfield also occasionally visited Piqua to lead religious services

and speak to the Anshe Emeth Sunday School students.[97] At the time, he was one of two rabbis

in that city.

Building the new Anshe Emeth synagogue cost approximately $20,000. In 2021, this sum

would be comparable to $320,400 after accounting for inflation. Half of the necessary funds

were donated by Leo Flesh.[98] The other $10,000 was raised by a wide collection of individuals

including most notably the members of the Anshe Emeth Sisterhood, which was formerly known

as the Jewish Ladies’ Aid Society. Fundraisers for the construction project organized by the

Sisterhood included four bake sales, four dinners, a series of rummage sales, and raffles.[100] The

efforts of the Sisterhood, which helped to ensure the new synagogue could be created free of

debt, were recognized by similar organizations in other nearby Jewish communities. In 1922,

Piqua was selected as the site of the district meeting for the Ohio State Federation of Temple

Sisterhoods, drawing many people from Dayton and Springfield.[101] Members of the Sisterhood,

which in 1920 had 15 members, also continued to support the Anshe Emeth Sunday School. In

1922, two children were confirmed from the school. The students and teachers also led special

Hanukkah and Passover services.[102] By 1924, the Sisterhood had created a new library at Anshe

Emeth for the Sunday School.[103]

During this period in the Sisterhood’s history Fannie Louis, the wife of Meyer Louis,

served as president of the organization. When the new Anshe Emeth synagogue was dedicated,

Fannie was honored by being chosen to kindle the ner tamid, or eternal light found at the front of

the sanctuary. A ner tamid is found in most synagogues near the Torah ark and it serves to

remind congregants of the continuous presence of the divine. Interestingly, Fannie was a native

of Delaware, Ohio, and her parents, Rachel and Samuel Stern, were likely among those who

traveled significant distances in the late 1800s to attend Anshe Emeth on holidays. Rachel’s

maiden name was Friedlich. The officers of Congregation Anshe Emeth in 1923 were as follows:

Moses Flesh, president, Jacob Wendel, vice president, Meyer Louis, secretary, and Louis

Ostertag treasurer. It is of note that Louis Ostertag served as treasurer of the congregation from

1918 up until 1947.[104] In 1924, Raphael Louis took on the role of president of the congregation

and retained this position until 1947, when he was succeeded by Joseph Kastner and elected

honorary president for life.[105] Raphael’s brother, Meyer, frequently served as a lay leader in the

new synagogue. In some advertisements published in The Piqua Daily Call Meyer’s title is given

as Reader.

Anshe Emeth was reincorporated with the State of Ohio in 1924. The signatories of the

congregation’s new Articles of Incorporation were: Moses Flesh, Marcus A. Lebensburger, Leo

Louis, Meyer Louis, and Louis Ostertag. The Jewish community of the Upper Miami Valley also

continued to keep informed of events impacting their coreligionists abroad during this period. In

1926, the local Jewish families raised $4,721 to support Jews suffering in Europe.[106] Local

developments also included the arrival of several new Jewish families in the region. In Piqua

newcomers included Frances and Robert F. Albright, David and Grace Hirsch, and Benjamin and

Ray Kuppin. The Albright family came to Piqua after Robert, who more commonly went by his

middle name Frank, became associated with the Rapp’s Clothing Store. David Hirsch moved to

Piqua with his wife and son, Allen, in 1925 to take a position with the Cottage Baking Company.

The family remained in Piqua until 1934 but maintained close connections with the Columbus

Jewish community.[107] In 1931, Allen had his bar mitzvah at Congregation Agudas Achim in

Columbus. Benjamin and Ray Kuppin were living in Piqua by 1920, and by 1930 Ben was

running the Eagle Billiard Hall. The couple also had at least four children, Bertram, Frank,

Hannah and Herbert. All of these children moved away from Piqua as adults.

Jews also continued to move into Greenville, Sidney and Troy. New residents included

Simon Brotkin, Freda and Harris Harbor, Minnie and Morris Jaffe, Morris and Rose Kaufman

and Abraham and Lena Rokoff. Simon, who was nicknamed Si, moved to Greenville from

Massachusetts in the late 1920s to work with the Greenville Iron and Metal Company, which was

owned by an uncle.[107] Later, in 1937, he opened The Smart Shop, which was located along South

Broadway.[108] This store sold women’s clothing, and later children’s wear. In time, Simon helped

his brother, Isidore, open a branch of The Smart Shop in Sidney, and a branch was also opened in

Piqua, where Simon moved following his marriage to Sara Rosenblatt. Sara was from Tiffin,

Ohio.[109] Max Brotkin, the father of Simon, also moved to Greenville to help run the store there.

He was joined by Ida, his wife.[110]

Both the Harbors in Troy and the Jaffes in Greenville were active in the scrap metal

industry. Much like the clothing industry for earlier Jewish immigrants, the disproportionate

presence of Jews in the scrap metal industry was due to the recent development of the trade and

its accessibility to immigrants at a time when discrimination closed many other professional

avenues. Operating a scrap yard was also particularly attainable for many Jewish immigrants

because of its low startup cost and scalability. Religious entrepreneurs could also create their

own work schedules around holidays and other observances which would not have been

permitted in larger factories. By 1930 Fortune magazine estimated that 90 percent of scrap metal

yards in the United States were owned by Jews.[111] Harris Harbor’s business was known as Harris

Harbor Recycling while Morris Jaffe’s enterprise was called Greenville Iron & Metal Company.

Morris Kaufman of Sidney and Abraham Rokoff of Troy worked as clothiers. The tradition of

enterprise within the local Jewish community would continue into the 1930s, but challenges

would impact more than one family.

The Depression & War Years: Jewish Life in the Upper Miami Valley in the ‘30s and ‘40s

On January 29, 1930, the three-story Mickler Department Store on Main Street

experienced a major fire that began in the basement. The damages were estimated to be

$200,000.[112] This sum would be comparable to over $3,200,000 in losses in 2021. In addition to

the Mickler store, Ostertag Brothers, located next door, was also impacted. At the time, Kenneth

Shofstall, a reporter for The Piqua Daily Call, reported that the blaze was, “one of the most

disastrous fires in the history of the city.”[113] Within three weeks Bert and Louis Ostertag made

plans to relocate to a space in the Piqua National Bank building with a new stock of

merchandise.[114] Harry Mickler was able to rebuild his store, but in 1935 he declared

bankruptcy.[115] He departed Piqua for Columbus by 1938.

It appears that Harry was not the only Jew to leave the Upper Miami Valley during the

1930s. In 1930, the American Jewish Yearbook, which continues to be printed annually by the

Jewish Publication Society, estimated that the Piqua area was home to 90 Jews.[116] By 1941 this

estimate had fallen to 75.[117] The adult Jewish population within Piqua alone was estimated to

number 20 in 1937.[118] It should be noted, however, that these population estimates are useful

only for providing a general sense of the Jewish community’s size. It is likely, however, that the

estimates are not entirely accurate since determining the size of any religious community in the

United States is a challenge due to the lack of official data on the subject. It is even more

difficult to accurately assess the size of a minority religious community whose members may

feel hesitant to answer questionnaires or publicly affiliate.

While undoubtedly modest in size, the Jewish community participated actively in

interfaith activities in Piqua. By the late 1930s, an Inter-Church Council existed which included

Anshe Emeth as a member. Non-Jewish ministers were also invited to speak at Anshe Emeth.[119]

Similarly, rabbis were invited to address primarily non-Jewish audiences on occasion. For

example, in 1932 Rabbi Jacob Tarshish of Columbus spoke at the graduation exercises for Piqua

High School.[120] While religious tolerance generally was practiced, there were contemporary

examples of anti-Jewish sentiment in the region. Clara Ziment, who grew up in Piqua during the

1920s and 1930s, wrote in a 2012 essay on her spiritual journey that Jewish children in Piqua

were sometimes harassed and hit by Catholic school students who were taught at the time that

Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus Christ. Clara also wrote that she experienced some

indirect comments in the local public schools about her difference as a Jew.[121] Clara is the

daughter of Dina and Samuel Kastner and, after graduating from Piqua High School, she

attended the Art Academy of Cincinnati and later the Pratt Institute in New York City. She had a

successful career as a cartoon artist.

Congregation Anshe Emeth continued to be a center for Jewish life, attracting members

from across Miami County and surrounding areas. By the mid-1930s, some congregants were

coming from Urbana to the east.[122] The Sisterhood worked to support congregational activities

by organizing card parties, the occasional rummage sale and other fundraisers. Its members also

continued to support the Sunday School and its confirmation classes. In 1941, two children were

confirmed at Anshe Emeth, Bertram Kuppin and Mildred Murstein.[123] No record of a local

Jewish men’s organization exists, however, until April 13, 1944. On this day the Anshe Emeth

Lodge, also known as Lodge 1523, of B’nai B’rith was formed.[124] Representatives from the Zion

Lodge in Columbus assisted with the installation ceremony. Early members came from Covington, Greenville,

Piqua, Sidney, St. Paris, Troy, Urbana, and Versailles.[125] By 1951, the

lodge had around 25 members. By 1945, a Women’s Auxiliary was also formed to complement

the activities of the men’s lodge.[126]

A number of Jewish families are known to have moved to the Piqua area in the 1930s.

Included among them are the Bettmann, Brateman, Fishel, Gilfer, Lee, Murstein, Perlis,

Solomon, and Sussman households. Jacob and Helen Bettmann lived in Piqua only for a short

time after Jacob relocated in 1933 or 1934 due to his work with the Favorite Stove and Range

Company. Prior to this move, the couple had lived in Cincinnati.[127] It should also be noted that

Jacob, who was a longtime member of the Favorite Stove board of directors, likely lived in Piqua

for a brief period in the early 1900s. For many years, Favorite Stove, which was originally based

in Cincinnati before moving to Piqua in 1887, was the city’s largest manufacturer.[128] The

Depression severely impacted the company, however, and in 1935 the firm was liquidated. Most

of its former assets were purchased by the Foster Stove Company out of Ironton, Ohio.[129] Jacob

died that same year at the age of 70. Helen, who had lived in St. Joseph, Missouri, before her

marriage in 1895 appears to have left the Piqua area after her husband’s death.[130]

Herman Brateman, Trina Fishel, and Harry Gilfer all worked in the accessory or clothing

business. Brateman’s, a women’s and children’s clothing store located on South Broadway in

Greenville, was opened between 1939 and 1942. Trina worked at dress shops in both Piqua and

Sindey beginning in the mid-1930s before moving to Cleveland in 1951 to take a position with

Glanz Furs.[131] Harry owned a men’s clothing and tailoring shop along North Main Avenue in

Sidney by 1936. Other recent arrivals in the area engaged in various kinds of work. Harry and

Jennie Lee, who lived in Covington by 1937 operated the Cove Theater in that town.[132] Joseph,

the son of Harry and Jennie, also helped to manage the theater. Joe was active in the local

community. From 1945 to 1946 he served as the second president of the Anshe Emeth Lodge,

and his wife, Ruby, was active with the B’nai B’rith Woman’s Auxiliary. Joe was also the

co-owner and editor of Stillwater Valley News, a Covington newspaper. Elliott and Libbie

Murstein opened the Elliott Furniture Store in 1934 at the corner of West Ash and North Wayne

Street. This business continued in Piqua through the 1960s. In 1951, Louis and Mildred Berman

moved to Piqua from Cleveland to help run Elliott’s Furniture. Mildred was the daughter of

Elliott and Libbie. A few years later, Louis opened Elmur’s Furniture Store at the corner of East

High and Harrison Street, which he operated through 1963.[133] Louis’ life was cut short in 1967 at

the age of 43 due to an auto accident on Interstate-75.[134] At the time Louis was planning to open

a store in Dayton.

Dorothy and Seymour Perlis moved to Piqua from Toledo in 1938 to open a cleaning

business under the name XL Cleaners. In addition to his involvement with Anshe Emeth,

Seymour was also an early member of the Piqua Kiwanis Club, which was chartered in 1936.

Both Leonard Solomon and Harry Sussman were involved in the scrap metal industry. Leonard,

who was born in New Jersey, owned East Side Iron and Wrecking in Sidney. Later he also

opened another business, Leonard’s Auto Parts.[135] Both Leonard and his wife, Sarah, were

members of Anshe Emeth. Sarah was also active with the B’nai B’rith Woman’s Auxiliary, while

Leonard volunteered with the Boy Scouts and the Sidney Lions Club.[136] Harry Sussman moved

to Piqua in 1931 with his wife, Bessie, after spending seven years in Sidney. The couple

relocated so that Harry could take ownership of the Ohio Scrap Iron & Metal Company, which

had been founded by Solomon Dagan over 15 years prior. While residents of Piqua, it appears

that Bessie and Harry chose to attend Beth Abraham, a synagogue in Dayton, rather than Anshe

Emeth. Until 1943 Beth Abraham was an Orthodox synagogue.[137] The Sussman’s decision to

attend Beth Abraham rather than a local synagogue demonstrates how many of the more

orthodox Jewish households in the Upper Miami Valley continued to look to Dayton for

communal religious life.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked and soon millions of Americans were

called upon to enter the armed forces. Families, both Jewish and non-Jewish, in the Upper Miami

Valley, lent their efforts to support the war effort. Of the local servicemen, at least 11 were

Jewish. Their names were: Herman Barr, Herman Brateman, Daniel Garfield, Marvin

Halverstein, Erving Kastner, Norman Kastner, Sanford Kastner, Bertram Kuppin, Frank Kuppin,

Joseph Shuchat, and Benjamin Taubman. It should also be noted that shortly after the end of

World War II two other Jewish veterans, Charles Bailen and Louis Berman, relocated to Troy and

Piqua, respectively. Louis was an ensign in the United States Navy. Additionally, Alfred Flesh Jr.

and Henry Flesh, the grandsons of Leo and Gertrude Flesh, served during the war. Alfred Jr. was

killed in action, and to honor his memory Alfred Flesh Sr. established the Alfred L. Flesh Jr.

Memorial Trust in 1946 to benefit local community projects and civic institutions. Alfred Jr.

fought in the Pacific Theater.[138]

Other local Jewish servicemen saw action in the European Theater. Bertram Kuppin was

among these men. In 1945, Bertram was captured by the Nazis and held as a prisoner of war for

five months near Czechoslovakia before being released.[139] By the war’s end, both of Bertram’s

parents had died and, shortly after returning to the United States he, along with his other siblings,

left Piqua. The Nazi’s rise to power 12 years earlier prompted a wave of emigration from

Germany. Yet, the United States, along with most other countries at the time, allowed only a

modest number of refugees to enter the country. After the outbreak of World War II, this number

further decreased. Two of the fortunate people granted admittance into the United States were

Arthur and Margaret Werner, who settled in Piqua in 1939. For many years in Germany Arthur

managed a chain of stores. By November 1938, however, the Nazis confiscated all remaining

Jewish-owned businesses in Germany. Arthur was imprisoned for three weeks in the

Buchenwald concentration camp in the same year. On April 20, 1945, The Piqua Daily Call

published a letter from Arthur reflecting on his experiences and responding to those who

believed that reports coming out of Europe about the concentration camps were exaggerated. He

wrote:

Every day [sic] people of this town ask me if such terrible happenings are true. They

believe those stories might be exaggerated. As matter of fact I have been an inmate of the

concentration camp ‘Buchenwald’ in 1938, and I can confirm that those reports are true,

without any doubt. The chance to get out of this camp alive is only 100 to 1. I saw with

my own eyes my fellow prisoners dying beside me the same way as Mr. Richards

describes it in your paper today. If somebody should still have doubts, please, send them

to me.[140]

It is likely that Arthur and Margaret found their way to Piqua due to the support and

sponsorship of individuals from the local Jewish community. One group working to support

Jewish refugees at the time was the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). Leo

Flesh and Emanuel Kahn were two residents of Piqua who were active with the JDC. In 1942,

each was elected to the organization’s National Council.[141] It was also reported in the obituary of

Dina Kastner, written in 1990, that she assisted in the resettlement of two Jewish refugee families

from Germany.[142] No contemporary sources, however, reference the existence of a refugee family

in Piqua aside from the Werners. Evident in Arthur’s letter to The Piqua Daily Call, is the

responsibility he took upon himself to bear witness to the atrocities committed by the Nazis in

Europe. Shortly after his letter was printed, Arthur spoke to a Lions Club meeting about his

experiences.[143] Margaret also worked to educate others on what was happening in Europe. As

early as 1942 she was speaking to organizations about her experiences.[144] When Arthur and

Margaret arrived in Piqua, they were 56 and 47 years old respectively. Arthur at first secured

employment with the Orr Felt and Blanket Company and later he went to work at Yieldmor

Feeds until his retirement in 1965. Margaret had died six years prior.

During the late 1940s to mid-1960s, the Jewish population of the Upper Miami Valley

reached its largest size. According to the American Jewish Yearbook, by 1959 the local Jewish

community may have numbered as high as 225 people.[145] This number, however, was likely an

overestimation. A figure of 170 to 175, which is cited in other years, was likely closer to reality.

Families who arrived in Piqua between 1945 and 1950 included Charles and Zena Bailen,

Edward and Tillie Bailen, Elizabeth and Isaac Harrison, Bernice and Joe Klasman, and Bernice

and Maurice Schapiro. Charles and Edward Bailen did business together in Tory under the name

United Scrap Lead Company. Edward created the business and was later joined by his brother.

Elizabeth and Isaac Harrison, who were both natives of Cincinnati, moved to Piqua in 1947 after

Isaac began a new business venture, Barclay’s Menswear.[146] In 1949, Stanley joined his father in

the business. The enterprise enjoyed continued growth and by the 1980s Barclay’s began to offer

women’s apparel and accessories. As of 2021, Barclay’s Men’s & Women’s Clothiers is the

largest independent family-owned clothing store in the Miami Valley.[147]

Bernice and Joe Klasman also arrived in Piqua in 1947. The couple was brought to

Miami County after Joe took a position as city editor with The Piqua Daily Call. Before writing

in Piqua, Joe had experience reporting in East St. Louis, Huntington, Pittsburgh, and

Louisville.[148] His early assignments in East St. Louis included covering gang violence and

executions.[149] He would serve as the city editor for 28 years before retiring. Like Joe, Maurice

Schapiro worked as a newspaper reporter. He came to Miami County to take a position as the

Troy correspondent for the Dayton Daily News. Bernice and Maurice lived in Troy by 1947 and

they were involved in both Anshe Emeth and B’nai B’rith. Both organizations would see new

levels of activity during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Post-War Years: A Time of Expansion

The Post-War Years: A Time of Expansion

Mirroring the community as a whole, the

1950s were a boom time for the Anshe Emeth

Sunday School as youths aged into their

schooling years. By 1954 Sunday School

students were coming from Greenville, Piqua,

Pitsburg, Sidney, and Troy.[150] As families grew,

so too did Anshe Emeth and its resources. From

1950 to 1955 the congregation had enough funds

to secure the services of a Sunday School

principal, Morton Kanter. Prior to moving to

Piqua, Morton served in World War II and he was a Hillel

staff member at Miami University.[151]

He was also a student at Hebrew Union College before being ordained in 1955. Morton left

Piqua later in that same year to take a position as assistant rabbi at Temple Israel in Dayton. The

growth of the Sunday School also contributed to the addition of a one-story kitchen and social

hall at the back of Anshe Emeth in 1958. This addition, which was built at the cost of $25,000,

was used to house the Sunday School’s classes and provide additional event space for the

congregation.[152] Frank Albright and Seymour Perlis served as co-chairman of the building

committee.[153] At the time, it was estimated Anshe Emeth had between 35 and 40 member

families.

The year 1958 also marked the centennial of Anshe Emeth, and the anniversary was

observed with appropriate functions. Rabbi Stanley

Chyet, a research fellow at the American Jewish

Archives in Cincinnati, was the principal speaker at

the congregation’s anniversary celebration.[154] In

this same year, the congregation dedicated a new

Torah scroll, which was donated by Gertrude Flesh.

The Sisterhood, which sponsored events such as an