Rabbi Leopold Greenwald

A Biographical Study of the Hungarian-Born Orthodox Zionist, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald of Columbus, Ohio

by Rivka Schiller

Rabbi Leopold Greenwald[1] was born in what was then Sziget (Hung., also Máramarossziget; today Marmației, Romania), part of Transylvania,[2] according to his son, Jack Greenwald (b. 1928, Columbus, OH), on the Jewish holiday of Hoshana Rabbah, in 1888.[3] According to other sources consulted, R. Greenwald was actually born on the 12th of Tammuz 5649 or the secular calendar date of July 11, 1889.[4] His Hebrew name, Yekutiel Yehuda, stemmed from Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum (1858-1883), one of the leading rabbis of Sziget, and somebody whom R. Greenwald’s father greatly revered.[5] R. Greenwald died on the third intermediate day of Passover, the 19th of Nisan 5715 or April 11, 1955.[6] According to an obituary in Columbus’ Ohio Jewish Chronicle (now defunct and superseded by the Columbus Jewish News), R. Greenwald was in failing health prior to his death and was mourned by thousands. Of those manifold mourners, hundreds attended his funeral.

Greenwald’s popularity in his role as the longtime rabbi of Orthodox Beth Jacob Congregation of Columbus, Ohio, may be attested to not only because of the large mourner turnout, but also, because only two weeks earlier, he had been reelected to his eleventh consecutive three-year term. Given his long-term rabbinical service at Beth Jacob, which he joined in 1925, the late rabbi was said to have been “one of a half dozen rabbis in the nation who had served one congregation 30 or more years.”[7]

Thus ended the life of a man who was reputed for his great erudition, staunch defense of Hungarian Jewish Orthodoxy, and prolific pen, whose works are still consulted today.[8] But as we shall soon see, by painting a picture of R. Greenwald’s unfolding early years in début du siècle 20th century Central and Western Europe up through his middle and later years in Midwest America, he was all those categories, and more. Better stated, he defied an easy or pat categorization, as will be illustrated in the following biographical profile of his life.

As previously mentioned, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald was born and raised in Sziget, the same city in which the noted writer and Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel (1928-2016) would later be born. Indeed, according to Jack Greenwald, Mr. Wiesel informed him that he used to frequent R. Greenwald’s father’s, Rabbi Yaakov Greenwald’s bookshop.[9]

In his Hungarian youth, R. Greenwald studied at several yeshivot in Ungvár; Bonyhád; Satmar; Hust[10]; Undsdorf[11]; at the famed Pressburg Yeshiva, founded by Rabbi Moshe Sofer in 1806 (1762-1839; more commonly known as the “Chatam Sofer”), then overseen by Rabbi Akiva Sofer (1878-1959), the great grandson of the yeshiva’s founder[12]; and at the Frankfurt am Main Yeshiva,[13] where he came under the influence of the Hungarian-born Orthodox Zionist, Rabbi Nechemiah Anton Nobel (1871-1922).[14] It is worthy of mention that Rabbi Nobel was a close acquaintance of Zionist leader, Theodor Herzl (1860-1904). In addition, Rabbi Nobel was one of the founders of the Zionist Federation in Germany, and a participant in the 1904 Mizrachi convention in Pressburg [today, Bratislava, Slovakia], which will be discussed later in this paper.[15]

While in Frankfurt, R. Greenwald also attended courses at the local university in History and Philosophy and was an assistant professor at the rabbinical seminary. By the age of twenty, in 1908, R. Greenwald was awarded rabbinical ordination. He then served in professional roles in Hungary, including as rabbi of a Jewish community in Nagy Szeben, as well as a journalist for several Hungarian publications.[16] In 1913, while serving as rabbi in Nagy Szeben, he married Gisela Horowitz (1888-1957), the daughter of Rabbi Tzvi Halevi Ish Horowitz.[17]

It is worth stressing that R. Greenwald hailed from a traditional Orthodox family and was educated by teachers who were very much shaped by the religious zealotry of Rabbi Moshe Sofer and his disciples, who advocated a fierce resistance to “religious and cultural innovations.”[18] Indeed, his father, the aforementioned Rabbi Yaakov, himself an exceptional Torah scholar,[19] has been described as follows in the postscript of R. Greenwald’s posthumous publication on Jewish law, ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut:

Yaakov was a zealous fighter for Chareidi [i.e., what one might refer to today as “Ultra-Orthodox”] Judaism. In particular, R. Yaakov would rebuke his audience of listeners on the matter of educating one’s children [sons]. R. Yaakov was a huge opponent of secular studies and the study of foreign languages. He adhered to an old-fashioned line of thinking; and did not veer from that for anything. And he sermonized that one should give the Jewish child [boy] a complete education without any form of outside mixing.[20]

In light of the fact that Rabbi Leopold Greenwald would come to master several languages (chief among them Hungarian, Yiddish, Hebrew, German, and English) to varying degrees, and given that he would go on to attend university courses in enlightened Germany, his father’s extremely negative views regarding secular education and the acquisition of foreign languages are all the more ironic and glaring.

It is also worth stating that the Orthodox Hungarian Jewish milieu in which R. Greenwald spent his formative years was overwhelmingly anti-Zionist in its ideology. This is reflected in the fact that although Theodor Herzl, the major figure of modern-day political Zionism, hailed from Hungary, when he convened the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, the Zionist movement made very little headway in his homeland. This was especially true, though, in strongly Chasidic regions in northeastern Hungary, such as Sziget – the hometown of R. Greenwald – where, by the end of the 19th century, local Chasidic rabbinical dynasties such as Satmar and Vizhnitz had become firmly entrenched. Indeed, according to correspondence with R. Leopold Greenwald’s son, Jack, his father came from a Satmar Chasidic background (although he would later abandon the Chasidic practices).[21]

For the traditional Jewish stance vis-à-vis Zion was (and still is, for certain Jewish factions) that the return to the Holy Land, Eretz Yisrael [Israel], is dependent on the arrival of the Messiah. Until that time, according to this belief, it is a grave sin for any mortal being to use secular efforts to regain the Holy Land. What is more, in this pre-World War era, the previous line of thinking was more endemic among Chasidic Jews, even by comparison to other, non-Chasidic Orthodox Jews. Ironically, although Hungarian Jewry at this time was vastly divided – particularly among the factions of Orthodox and Neolog (i.e., the local variant of Reform Judaism)[22] – Orthodox Jews (both Chasidic and non-Chasidic) and Neolog Jews all saw eye-to-eye concerning Zionism, albeit for distinctly different reasons.[23]

Notwithstanding the Chasidic Orthodox influences R. Greenwald received from the environment in which he was raised, it is possible that certain Zionist-leaning individuals, such as the previously described Rabbi Nobel, left their mark on him. Yet one of the perhaps most impactful events in the young life of the future Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, was one that occurred in the late summer of 1904, when R. Greenwald was a mere fourteen years old. It was then that the first World Congress of the Orthodox Zionist organization, Mizrachi, took place in Pressburg.[24] At the time, R. Greenwald was a yeshiva student in Undsdorf. He and seven other students who were, in his own words, “interested in world problems, surreptitiously read a newspaper, discussed important matters, attempting to solve the eternal painful Jewish question,”[25] set out in secret on their own – without the permission of the yeshiva’s director – traveling by train to attend the Congress, some 500 miles away.

The Congress itself was chaired by the founder of Mizrachi, Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines (1839-1915), who gave the opening address in Hebrew. Other religious and communal leaders included: the aforementioned Rabbi Nobel; Rabbi Nachum Grinhaus from Troki (Trakai), Lithuania; Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Landau (1892-1928) from Poland[26]; and Samu Bettelheim (1872-1942), who founded the first Hungarian Zionist group in 1897 and was also one of the organizers of the Congress in 1904.[27] Yet, at the same time, R. Greenwald recalls how taboo the Congress he attended was in the eyes of many fervently Orthodox Jews. This may be seen in the following: “The well-known Gaon Rabbi Simcha Bunim Schreiber, the rabbi of Pressburg, left his home so as to avoid the entire gathering; the religious judges and learned men looked with superstition upon the entire matter.”[28] Rabbi Simcha Bunim Schreiber (1842-1906), also known by the surname “Sofer,” was the scion of the previously discussed Sofer rabbinical dynasty.[29]

It is clear from the positive tone of R. Greenwald’s essay on the Zionist Congress of 1904, that even forty-some years later (when he wrote his recollections), the event was singular and made a major impression upon him. Indeed, he proudly relates that he “attended all the meetings, heard everything, went along everywhere, heard the doctors of the pious Pressburg Jews.”[30] Perhaps it was this very event that served as the greatest driving catalyst for the lifelong active involvement R. Greenwald demonstrated toward Zionism and Mizrachi, in particular.[31] In addition, according to his son, Jack, R. Greenwald was already a secretary for the Mizrachi in Sziget, and subsequently a “major player in the Zionist movement” in Columbus, Ohio.[32]

During the period that R. Greenwald spent learning in yeshivot in Central and Western Europe, whenever he had a break between semesters,[33] he would demonstrate his great love and curiosity for Jewish history – especially that of Hungarian and neighboring communities – something to which he would later devote several of his books and articles. For example, he states in his book about Jewish communities in Meḳorot le-ḳorot Yiśraʾel: le-ḳorot ha-ḳehilot-Yiśraʾel bi-medinot Slovaḳyah, Ungaryah, Ṭransilvenyah ṿe-Yugoslavyah, that “I visited the old and new Jewish cemetery (in Undsdorf), I dug through old documents, Jewish communal ledger books … I also asked the elderly folks about days past vis-à-vis the Jewish community of Undsdorf. And come to think of it, it was then that my fate was sealed to work with the history of our people.”[34]

This was considered an extremely unconventional and even disparaged pastime for a yeshiva student from R. Greenwald’s religious Orthodox background. In general, according to Nathaniel Katzburg (b. 1922), the Hungarian-born Israeli historian, “Jewish historiography in Hungary was almost entirely the realm of the Reform rabbis.”[35] Furthermore, “the study of Jewish sources in which the internal life was reflected, was entirely neglected – Jewish community ledger books [i.e., pinkasim], writings on headstones, Jewish legal and Responsa literature and more.”[36] As Katzburg underscores, this was precisely the sphere of research to which R. Greenwald devoted himself: that of rabbinical histories; the histories of Jewish communities and spiritual life, as well as those of religious and Torah-observant Jews.[37] Moreover, R. Greenwald viewed himself as having been tasked with the responsibility of safeguarding Hungarian Jewish historical sources and rescuing them for generations to come.[38]

Perhaps deriving inspiration from the historically- and genealogically-inclined research he conducted periodically in Jewish cemeteries (and presumably also in synagogues and other repositories of Jewish community records), R. Greenwald published a book about the highly controversial rabbinical figure, Rabbi Yonatan Eybeschutz (ca. 1694-1764)[39] before he was yet twenty years old. The title of that first of many books is Toldot gedole ha-dor ḥ”ʼ haniḳraʼ bet Yehonatan. On account of that work, in which he defends the frequently maligned Rabbi Eybeschutz, R. Greenwald was already internationally renowned even before immigrating to the United States, in 1924.[40]

Yet, as indicated earlier-on, R. Greenwald defies easy labeling or categorization. For on one hand he went out of his way to attend the Zionist Congress in Pressburg, something that was considered rather heretical in his circles and may even have risked his being suspended or expelled from the yeshiva in Undsdorf. On the other hand, he began investing much of his free time and personal research into Jewish history – something that was much more closely associated with Reform [i.e., Neolog] rabbis than with an Orthodox Jew of his pedigree.

Nevertheless, he also had contempt for (secular) Zionists, Neologs, “Enlightened Thinkers” [i.e., Maskilim] and anyone else whom he viewed as a threat to Orthodox Jewry. This may be seen in some of the following scathing excerpts that R. Greenwald printed in the Orthodox Jewish newspaper, Machzikei Hadas, whose revealing title translates to: “Adherents to the Religion,” in January of 1912:

In every generation we have a great war. Wars of the light and darkness. Wars of justice and uprightness and chaos. Wars of the truth and lie … Wars of insight and blindness. War for God against Amalek from one generation to the next. In every generation there stand upon us people to suppress the glory of Jacob.[41] So, too, it is now with Hungary … The anti-Semitism in Hungary is only [aimed] at those Jews who are lax in their belief.[42]

In this same article, R. Greenwald denigrates the Maskilim, whom he calls “evil doers” who have “defiled the holy,” as well as “the honor of Israel.”[43] Similarly, he also refers to the Zionists as “defilers of the holy and defilers of love of their homeland,”[44] singling out one such well-known Russian-born Zionist writer and activist, Peretz Smolenskin (1842-1885). Likewise, he makes it clear that although the Neologs – the Jewish reformers – may want Hungary’s Orthodox contingency to unite with them for the sake of gaining greater autonomy, the Orthodox will never cede to them.[45] Clearly, even though R. Greenwald had intellectual and Zionist leanings and interests in matters that were rather incongruous with his religious upbringing, he absolutely did not view himself as belonging to the camp of the Neologs, Maskilim, or (secular) Zionists.

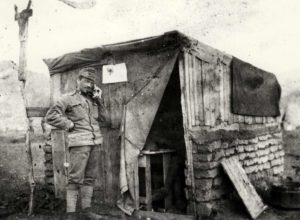

During the First World War, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, a major Hungarian patriot, freely enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian army, but not as a rabbi or chaplain. Rather, he served as a telegraph operator, after being sent for training to a school for telegraph operators in Budapest. In this significant and dangerous role, while stationed on the Serbian front in Albania, he “conducted the Passover seder over the wires for Jews in seven camps covering two hundred miles.”[46] In his own words, a Passover evening that began in a rather gloomy mood, due to R. Greenwald’s separation from family and the clouds of war, actually concluded on an upbeat tone and a feeling of triumph. This may be seen in the following quote from R. Greenwald in an article he wrote, which was based on excerpts from his book, Sefer ha-zikhronot: kolel et kol ha-telaʾot ṿeha-ṭilṭulim asher metsaʾuni be-meshekh ha-milḥamah ha-gedolah be-ʻomdi mezuyan mul ha-oyev:[47] “And for the first time in the air over Albania from station to station, the voice of Jacob was lifted in prayer to the Lord on this joyous festival.”[48]

It was not long after the Great War that R. Greenwald, who apparently wanted to be a writer and journalist – not a professional rabbi – decided to come to America, due to growing anti-Semitism in Sziget, which had since become part of Romania in the wake of the war. According to R. Greenwald’s son, Jack, and his grandson, James Greenwald, the tipping point in reaching this decision was an anti-Semitic incident that occurred on a train in which a local citizen attacked R. Greenwald.[49] In spite of the following admonitions R. Greenwald received against immigrating to the United States, he ultimately came to the country with his wife, Gisela, and two sons, Andrew and Ernest. In the words of Jack Greenwald:

Defying his parents and his wife’s parents, the chief Rabbi of Sibiu, Romania, who told him that he was going to a “treife medina,” my father left Europe in 1924 for New York City, without a job and not speaking the language.[50]

The Greenwald family was fortunate to be admitted to the United States, given that this was the beginning of an era during which quotas became strictly enforced against immigration that strongly affected Jews (and other ethnic groups and nationalities).[51] But since his professional training had been as a rabbi and he had no knowledge of the English language before coming to this country, R. Greenwald ended up spending several months serving as rabbi of a synagogue in Brooklyn, before making the final leap in the spring of 1925 to Columbus, Ohio, where he would serve as rabbi of Beth Jacob Congregation until his death in 1955.[52]

It goes without saying that the move from Central Europe to a small urban center in Midwest America must have come with its share of both religious and cultural changes and challenges for Rabbi Leopold Greenwald. This will be reflected in certain events that took place involving Beth Jacob Cong. and its congregants; and will be addressed in greater detail in the forthcoming part of this paper.

At the Beth Jacob Congregation, an Orthodox synagogue established in Columbus in 1898, R. Greenwald was welcomed by “six out-of-town rabbis and more than eight hundred guests”[53] at his installment in August of 1926, and was presented with a three-year contract, which stipulated that he would be paid a weekly salary of forty dollars (around $575.00 USD today). He was selected out of eight candidates and as previously noted, already had an established name as a distinguished rabbinical scholar and historian, on account of his first and subsequent book and article publications.[54]

Once at the synagogue, R. Greenwald began giving sermons twice every Sabbath in Hebrew and Yiddish, though none in English. He demonstrated his broad range of knowledge and interests, through the Friday evening Forums lectures he gave. A small sampling of these eclectic lectures, which were steeped in history, philosophy, and theology, may be seen in the following titles: “The Meaning of the Declaration of Independence,” “George Washington and the Jews,” “History of Medieval Jewish Philosophy,” and “An Evaluation of the Historiography of Flavius Josephus.” Among the debates and symposia offered within the “Forum” format, was one entitled, “Is the Merchant of Venice Anti-Semitic?,” which was heatedly debated in 1933 between R. Greenwald and Columbus physician, Dr. Benjamin W. Abramson.[55]

In a similar, but seemingly more ideologically radical vein, even for an avowed (religious) Zionist such as himself, R. Greenwald held celebratory events at Beth Jacob to honor the memory of Zionists, Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) and Chaim Nachman Bialik (1873-1934). Herzl was born into a secular Hungarian Jewish family and remained thoroughly assimilated throughout his brief life, not even bothering to circumcise his only son, never attending synagogue, and only stopping short of baptizing his son out of respect for his own father’s wishes. In a word, as described by one scholar regarding Herzl’s sense of Jewish identity and affinity for Jewishness: “He was not of the people.”[56] Bialik came from a religious Jewish background, attending the famed Volozhin yeshiva when he was seventeen years old. However, he rejected the Orthodoxy of his youth, becoming a Maskil – and ultimately, the national poet of Israel.[57]

Finally, R. Greenwald did something that would seem utterly anathema to his Hungarian Orthodox separatist weltanschauung: He invited secular Zionist speakers into his synagogue to speak before his congregation. This included such public figures as Louis Lipsky (1898-1976),[58] Golda Meir (1898-1978),[59] and Abba Hillel Silver (1893-1963).[60] According to R. Greenwald’s son, Jack, even if his father hosted Abba Hillel Silver, a highly acclaimed Reform rabbi and Zionist activist, at Beth Jacob, he would never have regarded or addressed him as “Rabbi.” Rather, R. Greenwald addressed a Conservative or Reform rabbi as, “Doctor.”[61] This was presumably because he did not consider such individuals to be legitimate rabbis.

It is somewhat difficult to believe that the same thoroughly Hungarian and Orthodox-bred rabbi who shunned Maskilim, could bring himself to offer such seemingly taboo subject matter in a public forum on the Sabbath; or for that matter, to honor or host openly secular Zionist Jews in his synagogue. In the guise of the unyielding upholder of Orthodoxy, he would periodically denounce kosher butchers who opened their shops too early after the end of the Sabbath. On one noteworthy occasion in the 1920s, he even canceled an entire season of his Friday night Forum lectures, because he learned that a congregant had attended one of his lectures by driving to the synagogue – an outright Sabbath violation according to the Orthodox tradition.[62]

Perhaps even more indicative, though, of R. Greenwald’s ongoing sense of mission and responsibility for upholding and protecting Orthodoxy, may be seen in something that occurred later in his life, when he was already in his late 50s. Upon the publication of Rabbi Mordechai M. Kaplan’s (i.e., the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism) new Sabbath prayer book in 1945, R. Greenwald would be among those rabbis who publicly denounced the maverick rabbi, decrying his prayer book as atheistic and urging that it be burned; that Kaplan himself be placed in cherem (i.e., excommunication according to the Jewish tradition), and that any so-called rabbi associated with the prayer book had no right to call himself a rabbi.[63]

Yet despite his apparent personal dislike for the secularity – or even heretical approach – of Zionists such as Abba Hillel Silver, R. Greenwald himself remained a steady and active (religious) Zionist, becoming a member of the executive board of the Mizrachi and a leader of Zionist activities within the Columbus Jewish community. At the same time, he was a member of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, also known in Hebrew as the Agudat ha-Rabbanim (“Union of Rabbis”).[64] The aforementioned entity, which represented Judaism’s right-wing and was first convened in 1902, only accepted rabbis – individuals such as Rabbi Leopold Greenwald – who had been ordained in the Orthodox yeshivot of Europe, “and saw its role as defending tradition against the trials of American acculturation.”[65]

During World War II, R. Greenwald was especially active in communal service that involved Jewish communities overseas. Within this context, he was constantly involved in raising funds to help desperate Jews and yeshivot in Europe suffering under Nazism. As such, he joined approximately 400 other Orthodox rabbis[66] who heavily comprised the Agudat ha-Rabbanim, the Vaad ha-Hatzala (“the Rescue Committee”),[67] and the Agudat Yisrael (“Union of Israel”) organizations, joining forces with the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe (commonly referred to as the “Emergency Committee”), in Washington, DC, on October 6, 1943, only three days before Yom Kippur. The mission of this trip that has colloquially come to be known as the “rabbis’ march,” was to gain an audience with then President Franklin D. Roosevelt and persuade him to take more proactive measures in aiding and rescuing European Jewry, much of which had already been murdered in the death camps. Disappointingly, Roosevelt refused to see or even hear the group of religious Jewish protestors.[68]

Shortly after the “rabbis’ march,” the local Ohio Jewish Chronicle ran an article on its front page attesting to Rabbi Greenwald’s involvement with this rescue effort, with the bold title, “Rabbi Greenwald Among 500 Rabbis to See President.”[69] The article related that “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, spiritual leader of Beth Jacob Congregation,” was among the several hundred orthodox rabbis who marched on Washington on Wednesday, October 6 [1943] to “petition immediate action by the President and Congress to save the millions of Jews trapped in Europe,” and that

proclamations issued at the Washington march by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada … asked that ‘the President warn the world that Jewish blood is not to be shed with impunity and that the President use his influence to open the doors of Palestine to the homeless Jews and to have the neutral countries create havens of refuge for the refugees.’[70]

Nowhere, though, in the article, did it make mention of the fact that President Roosevelt had shunned the group of rabbis who had made long-distance trips to have an audience with him about a most urgent matter that concerned millions of lives.

Although Jack Greenwald, R. Greenwald’s son, did not recall the details surrounding how his father came to participate in the “rabbis’ march” when recently asked about this,[71] he did have the following remarks about the event, which appear on the David Wyman Institute website (as seen in the following):

I remember well how my father, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, went to Washington, D.C. just before Yom Kippur with a number of other Orthodox rabbis, in a desperate effort to lobby President Roosevelt to do something to save the remaining Jews of Eastern Europe.

My father was, as most American Jews at that time, of the firm conviction that FDR was the great savior of the Jewish people. Roosevelt’s refusal to meet with the rabbis truly shocked my father.

On the other hand, the delegation of rabbis was greatly impressed with Vice President Henry A. Wallace, who greeted them at the Capitol. My father returned to Columbus, Ohio, very disillusioned, first over the refusal of FDR to meet with the rabbis and second, over the general apathy of most government officials, other than Vice President Wallace, whom the rabbis saw as a champion of the Jewish cause.[72]

In attempting to reconstruct the steps of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, both demographically and literarily – a challenge in itself, in part because his published and unpublished works remain scattered among several collections throughout the world, today[73] – I was alerted to fascinating correspondence that took place between R. Greenwald and a somewhat unlikely subject: Rabbi David Jacob Simonsen (1853-1932) of Copenhagen, Denmark. This is yet another example of R. Greenwald’s association with individuals who hailed from entirely different ideological and religious backgrounds.

Not only was Rabbi Simonsen, who served as chief rabbi of Denmark for a decade beginning in 1893, significantly older than R. Greenwald, but he was also West European both by birth and rabbinical training. Indeed, he was schooled first in Copenhagen and subsequently ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau, where he trained under Zacharias Frankel (1801-1875) and Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891).[74] It is also worth pointing out that the Breslau seminary was decidedly non-Orthodox in its orientation; many sources refer to it as a philosophical forerunner to the Conservative movement within Judaism and the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (in New York), and most of its graduates went on to serve in Liberal or Reform synagogues.[75]

Interestingly, R. Greenwald corresponded with Rabbi Simonsen for at least fourteen years, between 1909 and 1923, beginning when R. Greenwald was barely into his twenties.[76] How the two came to be correspondents is not entirely clear,[77] although both surely knew important Jewish personalities in common. Furthermore, both were bibliophiles curious about Jewish history and other areas of research. In addition, both were avid writers and contributors to Jewish publications.[78] For example, Rabbi Simonsen amassed a book collection of 100,000 volumes, which he ultimately bequeathed to the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen.[79] Supposedly, R. Greenwald had likewise amassed several thousand works by the end of his life. A significant portion of those works were donated by Gisela Greenwald, the rabbi’s widow, following his death, to the Hebrew Union College (HUC) in Cincinnati, Ohio.[80]

Two detailed handwritten Hebrew letters sent by R. Greenwald to Rabbi Simonsen were addressed only months before R. Greenwald set sail for the United States, in 1924. In the letter dated August 17, 1923, R. Greenwald provides a great deal of autobiographical details, such as the fact that he is presently thirty-four years old and that he served as a rabbi in Sibiu, Romania (formerly Nagy Szeben, Hungary), at which time he was only twenty years old. He further states that he was in the [military] service during the war [World War I], and that following that horrible event, he went to Budapest, where he was the editor of a Hungarian newspaper. He also adds that he published some of the following books:

Toldot mishpaḥat Rozenṭhal: toldot ṿe-ḳorot … Naftali Rozenṭhal u-shene banaṿ …; Sefer Ḳorot ha-Torah ṿeha-emumah be-Hungaryah: kolel matsav ha-Torah ṿeha-emunah, ṿe-hishtalshelut …; Le-ḳorot ha-Ḥasidut be-Ungarya [published in Budapest by “ha-Tsofah le-ḥakhmat Yiśraʼel,” 1921][81]; and four books in Hungarian (whose titles he does not include).

After seeing how bad the situation was in Hungary, though, R. Greenwald returned to Sibiu – now part of Romania. However, he came to the realization that he has no purpose or future here. As such, he has made plans to go to “America, which is now a blessed land,”[82] in which he has many friends who will help him get a position as a rabbi, a writer, or something else. For this reason, he has arranged to set sail to that country in which there is “freedom and love for man”[83] and where he will be able to work within the realm of Torah in a calm environment. Unfortunately, though, he admits that he is still lacking that which is most essential: money to make the voyage to America. Therefore, R. Greenwald asks whether Rabbi Simonsen knows of anyone well-off in his own surroundings who can provide him with a loan of one hundred dollars, which R. Greenwald will repay a few months after reaching his destination site.[84]

It is worth drawing attention to the fact that R. Greenwald addresses Rabbi Simonsen in Hebrew with the equivalent of “Mr./Sir Simonsen,” following this up with several honorifics. Similarly, in postcards written in German, R. Greenwald addresses the Danish rabbi as “Herr Professor,”[85] an extremely dignified manner of addressing an individual in the German language. However, again, these titles that R. Greenwald directs at Rabbi David Simonsen – in contrast to “Rabbi” or “Rabbiner,” are significant in that they demonstrate that R. Greenwald distinguished between Orthodox rabbis and rabbis from other denominations. This is consistent with what R. Greenwald’s son, Jack, said (and which is mentioned earlier on in this paper); that his father only reserved the rabbinical title for those individuals whom he believed to be worthy of the title – those being members of the Orthodox Jewish persuasion.

Another rather revealing letter that R. Greenwald wrote Rabbi Simonsen, dated October 21, 1923, provides additional insight into why the letter’s author perceived the need to leave his birthplace for an entirely foreign country. In Rabbi Leopold Greenwald’s own confiding words: “Here, in the city of my birth, Sziget, it has become too restrictive for me … and the life of the ghetto, and especially since I wrote my large article about the history of Chasidism in Hungary in the newspaper, ha-Tsofah le-ḥakhmat Yiśraʼel, I have become very fearful…”[86] He goes on to say that he has all his papers in order to set sail, but is still lacking his ship’s passage card, on account of his monetary situation. Yet again, he makes his former request regarding a loan of one hundred dollars, or even somewhat less for one year, which would be of significant help to him.[87] Apparently, R. Greenwald offended many fellow Hungarian Jews – so much so, that he no longer felt secure or comfortable residing among them – even to the point of wanting to immigrate to the United States.

A further example of how R. Greenwald mixed with Jews who came from diversely different backgrounds and religious ideologies from his own is reflected in his correspondence with Dr. Jacob Shatzky (1894-1956), who is perhaps most frequently recalled for his association with the historically mostly secular Jewish, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, as well as his many books regarding Polish Jewish history. In addition, Shatzky was a frequent literary and theater critic and commentator on popular Jewish culture.[88] Like R. Greenwald, Shatzky had an eclectic oeuvre of publications in multiple tongues attached to his name. But unlike R. Greenwald, Shatzky wrote about Jewish subject matter that was overall of a secular nature.[89]

The said letter that R. Greenwald addressed to Jacob Shatzky comes from 193- (?) and makes reference to two of R. Greenwald’s works: Otsar neḥmad: meʼasef mukdash la-halakhah ule-ḥokhmat Yisrael, a quarterly periodical on Jewish law and Responsa, which contains a defense of the Chatam Sofer in Pressburg[90]; and Toldot ha-kohanim ha-gedolim she-shimshu be-Yisraʼel me-Aharon ha-kohen ʻad sof Bayit sheni ʻim heʻarot ʻal ḥayye Yisraʼel ba-yamim ha-hem, hashpaʻat Bet ha-mikdash ʻal bene ha-Golah vele-korot ha-kitot be-Yisraʼel (1932), which according to R. Greenwald made an impact in Israel, and about which even [Chaim Nachman] Bialik wrote and held in high esteem. There is also a brief, but sanguine reference to Abraham Liessin (1872-1938), who was then editor of the secularist and socialist literary journal, di Tsukunft (The Future).[91] This was the same journal in which Shatzky wrote the previously cited glowing review of R. Greenwald’s, Sefer ha-zikhronot in 1926.[92] Again, R. Greenwald’s positive reference to Abraham Liessin is particularly noteworthy, since Liessin was one of the many East European-born Jews who initially received a traditional yeshiva education, yet broke with that background early-on. Rather, Liessin became an active member of the Jewish Bund, upon its inception in what was then Wilno, Poland, in 1897.[93]

Greenwald remained a prolific and multilingual writer of Jewish law, Responsa, and history until the end of his life.[94] Nevertheless, he never truly mastered the English language well enough to deliver sermons at Beth Jacob in the language. Mainly, he preached in Hungarian-dialect Yiddish, which many of the congregants – especially among the younger generation – had difficulty comprehending.[95] As Jack Greenwald related, this was not so much of an issue in the 1920s or 1930s, when there were still plenty of European-born native Yiddish-speakers. But by the 1940s, and certainly into the 1950s, it began to pose certain challenges, since far fewer congregants could now comprehend R. Greenwald’s spoken Yiddish.[96]

At the same time, though, R. Greenwald remained a popular and well-liked spiritual leader until the end of his life. This may be seen in light of the genuine and nostalgic words expressed about him by local Columbus Jews, even decades following his death in 1955. In the enthusiastic words of Lou Goodman, a Columbus Jewish resident who was interviewed for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society-Oral History Project in 1999 – nearly 45 years after R. Greenwald’s death – when asked about his former rabbi:

We had a great rabbi. My father got him but he, I can’t remember the name. He writes books. He wrote books and everything. Everybody knows him all over the United States. He was that kind of a rabbi. Greenwald … Respected [all] over the country. I mean, you say Greenwald … My God. Greenwald, man, like you’re talking about heaven.[97]

In a likewise ebullient and positive tone, Sylvia Schecter, a native of Columbus who was interviewed in 1974, had the following to say when asked about how Rabbi Leopold Greenwald’s arrival was regarded, and how he was perceived locally:

Then Rabbi Greenwald came. He was a doll. I loved him very much … Very religious. Very sincere. Dedicated to Judaism in all its phases. A sweet man … He was meticulous. Very well groomed. He had a lot of respect among the non-Jewish people. They loved him. They really did. And he was quite an author.[98]

The overlapping theme between both these recollections is that Rabbi Leopold Greenwald was a wonderful, well-liked and revered individual who was sincere in his Jewish observance. What is more, he was a significant author. Perhaps the most unique point that stands out among these recollections, though, is that not only was R. Greenwald well-respected by fellow Jews, but he was also regarded in high esteem and affectionately by Gentiles. This is remarkable, seeing as R. Greenwald appears to have traveled in a world that was heavily populated by Jews – oftentimes highly religious Jews – and spent much of his time devoted to his rabbinical studies and writing. Clearly, if R. Greenwald was on such good terms with the broader society, then this is an indication that he was not simply insular and with his head constantly steeped within the pages of a religious Jewish tome.

In the late 1940s, the Beth Jacob Congregation had ongoing discussions regarding establishing a new synagogue building in a different neighborhood, which subsequently led to the disbandment of the original synagogue building – replete with its traditional women’s balcony. As part of these congregational discussions, the demand was made by many congregants that the new synagogue not include a women’s balcony or a built-in mechitza [i.e., a physical barrier to divide between men and women, especially during prayers]. A sincere Orthodox rabbi, R. Greenwald adamantly opposed the removal of the mechitza, being “an unyielding opponent of seating men and women together at worship services.”[99] However, his congregation chose not to heed R. Greenwald’s wishes and do otherwise.

Greenwald, realizing he could not win an uphill battle that represented the changing winds of Jewish observance in post-World War II America, demanded that if there was not going to be a physical object of separation between men and women during prayer services, there must at the very least be separate seating of the sexes. Indeed, as I learned from Jack Greenwald, in the new synagogue building, men and women sat in pews in separate sections that were strictly cordoned off from one another with theater ropes. To quote Jack, who was most definite on this point: “I never saw any mixing or cross seating, nor did I ever hear of any such crossing or mixing.”[100] Sadly, within three years of the new synagogue’s dedication in the summer of 1952, R. Greenwald, whose already delicate health situation may have been further taxed by Beth Jacob’s new trajectory, died.[101]

As stated at the introduction of this paper, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald was mourned by thousands of disciples, both locally, nationally, and internationally. It goes without saying that his absence left a major void – not only in the Columbus Jewish community, but in the broader academic community that valued and admired his numerous literary contributions to Jewish law and Jewish history. As for the mechitza, it would not be reinstated in Beth Jacob Congregation, which continued to call itself “Orthodox,” until at least fifteen years following its removal, and two rabbis later.[102]

Conclusion

As conveyed multiple times throughout this paper, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald was an individual who defies easy or pat categorization. Although he hailed from a Jewish background that featured strict and unswerving Hungarian Orthodoxy as its hallmark, he clearly broke from that model even by the time he was a young adolescent. This may be seen, for example, in the fact that he made every effort to attend the Mizrachi Zionist Congress when he was a mere lad of fourteen. One must bear in mind that Zionism – even within a religious Jewish framework such as the Orthodox Mizrachi – was totally anathema, as well as verboten, in the milieu from which R. Greenwald hailed.

Presumably, had the director of his then yeshiva or his family learned of R. Greenwald’s attendance at this “taboo” event, he would have been removed from the yeshiva and promptly forced to return home under lock and key. It is difficult to surmise what might or might not have happened next, had this been the case. Perhaps R. Greenwald would never have become the erudite scholar and author that he did, and perhaps he would never have volunteered to serve in the Austro-Hungarian army, nor later immigrated to the United States. However, this is all difficult to say, as one can only play “guessing games” with alternate history and personal circumstance.

In either case, it is self-evident that R. Greenwald was somewhat “out-of-sync” in his early years with his personal milieu in Hungary; and to a great degree, the same might be said of him in his middle and later years, once firmly planted on American soil. Perhaps nowhere is this incongruity more evident, though, than by the end of his life, when R. Greenwald adamantly disagreed on the stance taken by his congregation regarding the removal of the mechitza in the synagogue’s sanctuary. When he saw that he could not win the all-out battle regarding the halachic [i.e., pertaining to Jewish religious law] need for a physical mechitza – something that may have been impossible to achieve at that time and place for a rabbi half his age and in far better health – he still succeeded in convincing his congregation to enforce separate pews for men and women during prayer services.

Overall, R. Greenwald was an independent thinker – some might even say an iconoclast or a heretic – who ultimately remained staunchly Orthodox yet broke away from the Chasidism of his youth. He was also a devoted Hungarian patriot, as reflected by his volunteering for the Austro-Hungarian military during World War I and the subject matter to which he devoted much of his writing: Hungarian Orthodox Jewry. At the same time, though, he appreciated the freedom and liberties – the more “open” outlook – American society could grant him when compared to his insular Jewish environs and anti-Semitic countrymen in Hungary. And quite impressively, he had the foresight to see that the Jews needed to have their own homeland in the form of Eretz Yisrael [Israel].

Greenwald was also self-driven, highly erudite, and fluent in several languages, as attested to by many sources. Although never trained formally as an historian of Jewish history, he succeeded in publishing a sizable number of books and articles on the subject. This was despite history not being viewed favorably in general by Orthodox Jews in his given sphere. Furthermore, he was open minded enough to value the knowledge and comradeship that could be gained by entering friendships and correspondences with other highly literate Jews – even if their given theological practices and beliefs differed from those of his own. This may be seen in the many correspondences that R. Greenwald cultivated with individuals ranging from the Liberal Rabbi David Simonsen of Denmark, to the secularly oriented Yiddishist historian, Jacob Shatzky, who originally came from – but rejected – the yeshiva world of Eastern Europe.

Appendix

Photograph of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald in military uniform, ca. 1917, engaged in telegraph work at Serbian front during World War I.[103]

Grinvald, Yekutiel Yehuda [Rabbi Leopold Greenwald], ca. 1925-1930, The Abraham Schwadron Collection, the National Library of Israel, Archives, Jerusalem, Israel. Photograph sent by editorial office of Múlt és Jövő[104] to Abraham Schwadron (1878-1957).[105]

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all the individuals across the United States and beyond who assisted me in various ways with my research into the life and legacy of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald. This list of “assistants” includes (not in any special order):

Dr. Moshe Sherman, my professor of American Jewish History at Touro College (Midtown branch, New York) and the individual who oversaw this research project, for his encouraging me to take on a subject matter that was somewhat “out of the box” for me; and for providing me with helpful articles and archival resources. His biographical sourcebook on American rabbis (cited in my bibliography) was indispensable to my research.

Carol Schapiro and Toby Krausz, reference librarians at Touro College (Midtown branch, New York), each of whom went out of her way to assist me in locating and ordering research material.

Jack Greenwald (Denver, CO), the last surviving son of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, and a wellspring of information about his late father. I greatly appreciate the time and patience he took to correspond with me via email and meticulously respond to my questions regarding his father and family history. I also thank him for the multilingual articles he sent me about his late father, which proved immensely useful to me in my research.

James and Gale Greenwald (Maryland), the grandson and granddaughter (by marriage) of R. Greenwald, both of whom took the time to speak with me long distance regarding Rabbi Leopold Greenwald and family history.

Mindy Cooper (Columbus, OH), a relative by marriage who is a native of Columbus with whom I corresponded about research material concerning R. Greenwald. She graciously sent me several helpful ideas and links.

Rabbi Avi Goldstein (Columbus, OH), the current rabbi of Beth Jacob Congregation, at which Rabbi Leopold Greenwald served several decades ago. He was extremely receptive to my research topic, took the time to discuss the late rabbi and the synagogue’s history with me, and sent me some difficult-to-locate, yet highly relevant, articles.

Dr. Allison Schottenstein (Cincinnati, OH), a native of Columbus and a personal acquaintance with whom I corresponded about research material. She was most helpful in directing me to appropriate sites and repositories.

Michoel Rotenfeld (Associate Director of Touro College Libraries, New York), a maven about obscure Jewish texts and articles who took a personal interest in my research topic and went out of his way to send me relevant material about R. Greenwald.

Thyria Wilson and Dr. Jeanne Abrams (Beck Archives, Denver, CO), both went out of their way to advise and send me pertinent material regarding R. Leopold, some of which had been written or recorded by his son, Jack Greenwald.

Nechama Carmel and Sara Olson (Orthodox Union, New York), editors of the Jewish Action quarterly magazine of the Orthodox Union, were kind enough to send me a difficult-to-locate article that was relevant to my study of R. Greenwald.

Toby Brief (Executive Director, Columbus Jewish Historical Society), with whom I communicated at great length about Rabbi Leopold Greenwald, for sending me copies of rare archival material pertaining to the esteemed late Columbus rabbi.

Eva-Maria Jansson (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen, Denmark), an archivist who responded in a timely and helpful fashion to my queries about the collection of Rabbi David Simonsen, which includes fascinating correspondence with R. Greenwald.

Daniella Levy (Tekoa, Israel), Hebrew-to-English translator of Akiva Ben-Ezra’s biographical essay on R. Greenwald: “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” included in Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald’s ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut. Ms. Levy generously shared her previously translated version of this Hebrew essay with me.

Bibliography

The Abraham Schwadron Collection. The National Library of Israel, Archives, Jerusalem, Israel.

Abramson, Ruth. Benjamin: Journey of a Jew. Columbus, Ohio: Alpha Pub. Co., 1987.

Ben-Ezra, Akiva. “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l.” In ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald. New York: Feldheim Publishing, 1955, 185-192.

Ben-Ezra, Akiva. “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l.” In ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, 185-192. New York: Feldheim Publishing, 1955. Translated by Daniella Levy as “Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Greenwald z”l (A Historical-Literary Appreciation).” Unpublished manuscript, May 2011. Microsoft Word file.

Bernstein, Louis, ed. Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. “Mizrachi.” Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1971: 175-180.

Bloch, Chaim. “Ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehudah Greenwald: Ha’arakhah — bi-mlot ‘arbaim shanah le-‘avodato ha-sifrutit 1908-1948.” In Le-Toldot ha-Reformatsiʾon ha-datit be-Germanya uve-Ungarya: ha-Maharam Shiḳ u-zemano: kolel ḥaye … Mosheh Shiḳ, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald. Columbus, Ohio: L. Greenwald, 708 [1948], [2]-9.

Cassedy, Steven. Building the Future: Jewish Immigrant Intellectuals and the Making of Tsukunft. Teaneck, NJ: Holmes & Meier, 1999.

Churgin, Pinchas, and Aryeh Gellman, eds. Mizraḥi: kovets yovel li-melʼot 25 shanah le-ḳiyumah shel Histadrut ha-Mizraḥi ba-ʼAmeriḳah. New York: Mizrachi Organization of America, 1936, 169-171.

David Simonsen Archives. Royal Danish Library, Manuscripts Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Diner, Hasia R. The Jews of the United States: 1654-2000. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Ferziger, Adam S. Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of Orthodox Judaism. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2015.

Ferziger, Adam S. “Hungarian Separatist Orthodoxy and the Migration of Its Legacy to America: The Greenwald-Hirschenson Debate.” Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (2015): 250-283. https://doi.org/doi:10.1353/jqr.2015.0007.

Ferziger, Adam S. 2010. Sofer Family. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sofer_Family (accessed September 12, 2019).

Glassman, Leo M., ed. Biographical Encyclopaedia of American Jews, s.v. “Greenwald, Leopold.” New York: Maurice Jacobs & Leo M. Glassman, 1935: 198.

Goldstein, Avi. “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald: Dazzling Scholar and Orthodox Defender: Chol HaMoed Pesach 5777.” Synagogue Speech, Columbus, OH, April 12, 2017, 1-6.

Goodman, Lou. “Interview with Lou Goodman.” Interview by Naomi Schottenstein. Columbus Jewish Historical Society-Oral History Project, January 21, 1999. https://columbusjewishhistory.org/oral_histories/lou-goodman/?hilite=%27greenwald%27 (accessed September 19, 2019).

Gorny, Yosef. Converging Alternatives: The Bund and the Zionist Labor Movement, 1897-1985. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2012.

Greenwald, Jack. “50th Yahrzeit of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Speech, Denver, CO: Ira M. and Peryle Hayutin Beck Archives of Rocky Mountain Jewish History, January 2005, 1-4.

Greenwald, Jack. “No Subject.” Received by Rivka Schiller, October 7, 2019. Email Correspondence.

Greenwald, Jack. “Rabbi Greenwald.” Received by Rivka Schiller, September 15, 2019. Email Correspondence.

Greenwald, Jack. “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Received by Rivka Schiller, September 10, 2019. Email Correspondence.

Greenwald, Jack, and Rafael Medoff. “The Day the Rabbis Marched, Testimonials from Relatives of Those That Marched.” The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, March 17, 2017. http://new.wymaninstitute.org/2017/01/the-day-the-rabbis-marched-testimonials-from-relatives-of-those-that-marched (accessed September 17, 2019).

Greenwald, James. “Interview of James Greenwald Regarding His Grandfather, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Telephone interview by Rivka Schiller. September 9, 2019.

Greenwald, Leopold. “Passover in Albania.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 11, 1941, 4.

Greenwald, Yaakov. Sefer helek Yaakov. Seini, Romania: I. Wieder Publishing House, 1923.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. A Chasidizmus Magyarországon. Budapest: s.n., 1918.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Zsidó Néplegendák. Budapest: s.n., 1921.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Otsar neḥmad: maʾasaf muḳdash la-halakhah ule-ḥokhmat Yiśraʾel. New York: ḥ. mo. l., 1942.[106]

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. “Ein shalom amar ko’.” Machzikei Hadas [Lemberg, Austrian Empire], January 26, 1912, 2-3.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Zikaron la-rishonim: kolel toldot ve-korot ha-gaonim asher hofi`u be-or hokhmatam ve-toratam. Satmar: M. Klausner, 1909.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Kol bo ʻal avelut: mevoʾar u-mesudar kol halakhot dinim u-minhagim mi-yom she-neḥlah ha-adam ʻad tom yeme avelut. New York: P. Feldheim, c1956.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Le-ḳorot ha-Ḥasidut be-Ungarya. Budapest: “ha-Tsofah le-ḥakhmat Yiśraʼel,” 1921.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Le-ḳorot ha-Shabtaʾim be-Ungariya. Ṿaiṭtsen: bi-defus M. Ḳahan, 1912.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Li-felagot Yiśraʾel be-Ungarya: matsav ha-Torah be-Erets Ungarya, milḥamot ha-yereʾim bi-vaʻale ha-reform … uve-sof ha-sefer ḳunṭres Zekher tsaddik. Deva: Defus Marḳoṿiṭsh ʻeṭ Friʻedmann, 1929.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Meḳorot le-ḳorot Yiśraʾel: le-ḳorot ha-ḳehilot-Yiśraʾel bi-medinot Slovaḳyah, Ungaryah, Ṭransilvenyah ṿe-Yugoslavyah. Berehovo, Czechoslovakia: Buckdruck S. Klein, 1934.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Sefer ha-zikhronot: kolel et kol ha-telaʾot ṿeha-ṭilṭulim asher metsaʾuni be-meshekh ha-milḥamah ha-gedolah be-ʻomdi mezuyan mul ha-oyev. Budapest: Bi-defus M. Z. u-M. Ḳaṭtsburg, 1922.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Sefer Ḳorot ha-Torah ṿeha-emumah be-Hungaryah: kolel matsav ha-Torah ṿeha-emunah, ṿe-hishtalshelut ha-Reformatsyah be-tokh ha-Yahadut ha-Hungarit mi-yom she-baʼu ha-Yehudim le-erets Hagar ʻad shenat ha-perud (ha-Ḳongres bi-shenat 629) ṿe-sibat hitpardut ha-Yehudim ha-Hungarim. Budapeshṭ: Bi-defus M.Z. ṿe-M. Ḳaṭtsburg, 1921.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. “Di ershte Mizrakhi konferents in Presburg” (“The First Mizrakhi Conference in Pressburg”). In Mizraḥi: kovets yovel li-melʾot 25 shanah le-ḳiyumah shel Histadrut ha-Mizraḥi ba-ʾAmeriḳah, edited by Pinchas Churgin and Aryeh Gellman, 169-171. New York: Mizrachi Organization of America, 1936.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut. New York: Feldheim Publishing, 1955.

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Toldot gedole ha-dor ḥ”ʼ haniḳraʼ bet Yehonatan. Máramarossziget: Grünvald Leopold, [1907 or 1908].

Greenwald, Yekutiel Yehuda. Toldot mishpaḥat Rozenṭhal: toldot ṿe-ḳorot Naftali Rozenṭhal mi-Mohr u-shene banaṿ Eliyahu ṿe-r. Shelomoh Rozenṭhal. Budapest: Bi-defus M. Z. u-M. 1921.

Greenwald Family Collection. Columbus Jewish Historical Society, Columbus, OH.

Heuberger, Rachel. Rabbi Nehemiah Anton Nobel: The Jewish Renaissance in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt, Germany: M. Societäts-Verl., 2007.

Hirsh, Yoel. “Der Sigut’er historiker: fun Siget Rumenya, keyn Kolombus, Ohayo” (“The Sziget Historian: From Sziget, Romania to Columbus, Ohio”). Oytsres (Treasures), Tevet 5773 (December 2012): 44-53.

Holtzman, Avner. Hayim Nahman Bialik: Poet of Hebrew. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Jansson, Eva-Maria. “Questions Regarding the Rabbi David Simonsen Archives.” Received by Rivka Schiller, September 20, 2019. Email Correspondence.

Katzburg, Nathaniel. “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l.” Sinai 37, no. 4 (1955): 277-281.

Katzburg, Nathaniel. “ha-Hisṭoriyografyah ha-Yehudit be-Hungaryah.” Sinai 40, no. 5 (1957): 313-314.

Klagsbrun, Francine. Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel. New York: Schocken Books, 2019.

Kőbányai, János. 2010. Múlt és Jövő. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Mult_es_Jovo (accessed September 15, 2019).

Kressel, Getzel, ed. Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. “Nobel, Nehemiah Anton.” Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1971: 1200-1201.

Landman, Isaac, ed. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. “Simonsen, David Jacob.” New York: The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc., [c1939-43]: 549-550.

Leiman, Shnayer Z. “R. Leopold Greenwald: Tish’ah be-Av at the University of Leipzig.” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 25, no. 4 (1991): 103-106.

Lipsky, Louis. Memoirs in Profile. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1975.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. The Zionist Career of Louis Lipsky, 1900-1921. New York: Arno Press, 1982.

Montefiore, Simon Sebag. Jerusalem: The Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 2012.

Nadell, Pamela Susan. Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1988.

Olitzky, Kerry M. The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Papers of Jacob Shatzky, RG 356. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Archives, New York, NY.

Papers of Samuel Ephraim Tiktin, RG 495. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Archives, New York, NY.

Patai, Raphael. The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2015.

“Rabbi Greenwald Among 500 Rabbis to See President.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, October 8, 1943, 1.

“Rabbi Greenwald Passes.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 15, 1955, 1.

Raphael, Marc Lee. Abba Hillel Silver: A Profile in American Judaism. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1989.

Raphael, Marc Lee. Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City: Columbus, Ohio, 1840-1975. Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society, 1979.

Raphael, Marc Lee. “75 Years of Synagogue Growth: Highlites of Beth Jacob’s Past.” Synagogue Journal (1974): n. pag.

Raphael, Yiẓḥak. Entsiḳlopedyah shel ha-Tsiyonut ha-datit: ishim, muśagim, mifʻalim. Jerusalem: Mosad ha-Rav Ḳuḳ, [1958]-1983: 1: 589-595.

“ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald: ahad ha-olim,” Apiryon 1 (1924): 312-313.

Rubenstein, Rabbi Samuel W. “Interview with Rabbi Samuel W. Rubenstein, 1974.” Interview by Marc Lee Raphael. Columbus Jewish Historical Society-Oral History Project, May 10, 1974. https://columbusjewishhistory.org/oral_histories/rabbi-samuel-w-rubenstein-2/?hilite=%27greenwald%27 (accessed September 19, 2019).

Rubenstein, Rabbi Samuel W. “Interview with Rabbi Samuel W. Rubenstein, 1994.” Interview by Linda Katz and Richard Neustadt. Columbus Jewish Historical Society-Oral History Project, June 6, 1994. https://columbusjewishhistory.org/oral_histories/rabbi-samuel-w-rubenstein/?hilite=%27greenwald%27 (accessed September 19, 2019).

Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Schecter, Sylvia. “Interview with Sylvia Schecter (Parts 1 & 2).” Interview by Marc Lee Raphael. Columbus Jewish Historical Society-Oral History Project, September 22, 1974. https://columbusjewishhistory.org/oral_histories/sylvia-schecter-1/?hilite=%27greenwald%27 (accessed September 19, 2019).

Schneiderman, Harry, and Izhak J. Carmin, eds. Who’s Who in World Jewry: A Biographical Dictionary of Outstanding Jews, s.v. “Greenwald, Leopold Z.” New York: Who’s Who in World Jewry, Inc., 1955: 295.

Schwartz, Barry L. Jewish Theology: A Comparative Study. Millburn, New Jersey: Behrman House, Inc., 1991.

Shapiro, Marc B. “Some Assorted Comments and a Selection from My Memoir, Part 2.” The Seforim Blog, 2019. https://seforimblog.com/2009/11/some-assorted-comments-and-selection (accessed September 18, 2019).

Shapiro, Robert Moses. 2010. Shatzky, Yankev. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Shatzky_Yankev (accessed September 19, 2019).

Shatzky, Jacob. Arkhiṿ far der geshikhṭe fun yidishn ṭeaṭer un drame (Archive for the History of Jewish Theater and Drama). Wilno, Poland; New York: Yidisher ṿisnshafṭlekher insṭiṭuṭ, 1930.

Shatzky, Jacob. Ḳultur-geshikhte fun der haśkole in Liṭe: fun di elṭste tsayṭn biz Ḥibaś Tsien (Cultural History of the Haskalah in Lithuania: From the Oldest Times Until Hibbat Zion). Buenos-Aires: Union Central Israelita Polaca en la Argentina, 1950.

Shatzky, Jacob. Spinoza bukh (Spinoza Book). New York: Spinoza Institute of America, 1932.

Shatzky, Yankev (Jacob). “Yidishe memuarn literatur fun der velt milkhome un der rusisher revolutsye” (“Jewish Memoir Literature from the World War and the Russian Revolution”). Di Tsukunft (The Future) [New York], vol. 31 (1926), 241-243.

Sherman, Moshe D. Orthodox Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Inc., 1996.

Shimoni, Gideon, and Robert S. Wistrich, eds. Theodor Herzl: Visionary of the Jewish State. New York: Herzl Press, 1999.

Silber, Michael K. 2010. Bratislava. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Bratislava (accessed September 12, 2019).

Silber, Michael K. 2010. Hungary: Hungary Before 1918. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Hungary/Hungary_before_1918 (accessed September 13, 2019).

Silber, Michael K. 2010. Sighet Marmaţiei. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sighet_Marmatiei (accessed September 12, 2019).

Silberschlag, Eisig, and Michael Berenbaum, eds. Encyclopaedia Judaica, second edition, s.v. “Greenwald (Grunwald), Jekuthiel Judah (Yekusiel Yehudah; Leopold; 1889-1955).” Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007: 81.

Stavsky, David. “A Mechitza for Columbus.” Jewish Life 41, no. 1 (Winter 1974): 22-27.

Weissblei, Gil. “About Schwadron (Sharon).” The National Library of Israel. Schwadron Collection. https://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/digitallibrary/photos/Schwadron/Pages/About-Schwadron.aspx (accessed September 19, 2019).

Wine, Sherwin T. A Provocative People: A Secular History of the Jews. Lincolnshire, IL: IISHJ-NA, 2012.

Wininger, Salomon. Große jüdische National-Biographie: mit mehr als 8000 Lebensbeschreibungen namhafter jüdischer Männer und Frauen aller Zeiten und Länder ein Nachschlagewerk für das jüdische Volk und dessen Freunde. Bd. 2, Dafiera-Harden, s.v. “Grünwald, Leopold (Jekutiel Jehuda).” Cernăuți: Druck “Orient,” 1927: 540-541.

Zimroni, Shlomo. “Me-sidrei gedolei Siget: R’ Yaakov Grinvald z”l.” Maramarosh-Siget, July 1970.

Zuroff, Efraim. The Response of Orthodox Jewry in the United States to the Holocaust: The Activities of the Vaad ha-Hatzala Rescue Committee, 1939-1945. New York: Michael Scharf Publication Trust of the Yeshiva University Press, 2000.

Archives Consulted:

American Jewish Archives (Cincinnati, OH)

Beth Jacob Congregation (Columbus, OH)

Columbus Jewish Historical Society (Columbus, OH)

Ira M. and Peryle Hayutin Beck Archives of Rocky Mountain Jewish History (Denver, CO)

The National Library of Israel, Archives (Jerusalem, Israel)

Ohio History Connection (Columbus, OH)

Ohio Jewish Chronicle Archives (Columbus, OH)

Ohio State University Special Collections (Columbus, OH)

The Royal Danish Library, Manuscripts Collection (Copenhagen, DK)

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Archives (New York, NY)

[1] Also known by several given and surname name variations, including: Yekutiel Yehuda; Jekuthiel Jehuda; Zalman Leib; Leopold Zalman; Grünwald; Grunwald; and Grinvald. For the sake of consistency, I will refer to Rabbi Greenwald as “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald” or “R. Greenwald” in the body of this paper. However, in the bibliography and footnote citations, I cite him as “Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald” (and in one instance, as “Leopold Greenwald”). Herein I retain the most commonly used version of his surname, along with the Romanized transliteration of his most commonly referenced Jewish given and middle names.

[2] Following World War I, Sziget, which had previously been the capital of Máramaros county in the Kingdom of Hungary, became part of Romania. For further related information, see for example: Michael K. Silber, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, s.v. “Sighet Marmaţiei” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010) https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sighet_Marmatiei (accessed September 12, 2019); Akiva Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” in ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald (New York: Feldheim Publishing, 1955), 185; Nathaniel Katzburg, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” Sinai 37, no. 4 (1955): 277.

[3] See: Jack Greenwald, “50th Yahrzeit of Rabbi Leopold Greenwald” (Speech, Denver, CO: Ira M. and Peryle Hayutin Beck Archives of Rocky Mountain Jewish History; hereafter referred to as “Beck Archives,” January 2005), 1. I thank Thyria Wilson and Dr. Jeanne Abrams of the Beck Archives (Denver, CO) for making this speech available to me.

[4] See for instance: Yiẓḥak Raphael, Entsiḳlopedyah shel ha-Tsiyonut ha-datit: ishim, muśagim, mifʻalim (Jerusalem: Mosad ha-Rav Ḳuḳ, [1958]-1983: 1): 589. Additional sources state that R. Greenwald was born on September 26, 1889 and September 26, 1888, respectively. See also: Moshe D. Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Inc., 1996): 83; Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City: Columbus, Ohio, 1840-1975 (Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society, 1979), 262; Harry Schneiderman and Izhak J. Carmin, eds., Who’s Who in World Jewry: A Biographical Dictionary of Outstanding Jews, s.v. “Greenwald, Leopold Z.” (New York: Who’s Who in World Jewry, Inc., 1955): 295; Salomon Wininger, Große jüdische National-Biographie: mit mehr als 8000 Lebensbeschreibungen namhafter jüdischer Männer und Frauen aller Zeiten und Länder ein Nachschlagewerk für das jüdische Volk und dessen Freunde. Bd. 2, Dafiera-Harden, s.v. “Grünwald, Leopold (Jekutiel Jehuda)” (Cernăuți: Druck “Orient,” 1927): 540.

[5] R. Leopold Greenwald’s father, Rabbi Yaakov Greenwald (1850-1928), was an adherent of the Chasidic leader, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, also known as the “Yetev Lev,” in honor of one of his Chasidic commentaries on the Torah. See: Yoel Hirsh, “Der Sigut’er historiker: fun Siget Rumenya, keyn Kolombus, Ohayo” (“The Sziget Historian: From Sziget, Romania to Columbus, Ohio”), Oytsres (Treasures), Tevet 5773 (December 2012): 47.

[6] See: Yiẓḥak Raphael, Entsiklopedyah: 589; Jack Greenwald, “50th Yahrzeit,” 1; Hirsh, “Der Sigut’er historiker”: 53; Samuel Ephraim Tiktin, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald,” n.d., Box 1, Papers of Samuel Ephraim Tiktin, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Archives, New York, NY.

[7] “Rabbi Greenwald Passes,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 15, 1955, 1.

[8] Perhaps most well-known and frequently utilized of R. Greenwald’s numerous works even today (c. 2019) is that of the compendium on the Jewish laws and rites of mourning, the Kol bo ʻal avelut, originally published in New York in three volumes between the years 1947-1952. According to Akiva Ben-Ezra, this work was of particular use to Jews residing in America, as R. Greenwald dedicated a few chapters to issues pertaining specifically to Jewish mourning in that country. See: Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” 189; Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: 83; and Eisig Silberschlag and Michael Berenbaum, eds., Encyclopaedia Judaica, second edition, s.v. “Greenwald, Jekuthiel Judah” (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007): 81.

[9] Presumably, when Elie Wiesel visited the Greenwald bookshop, it was no longer run by Rabbi Yaakov, who died in 1928, the same year in which Wiesel was born. After R. Yaakov Greenwald died, his son Avigdor took over the bookshop. See: Jack Greenwald, “50th Yahrzeit,” 1. Regarding R. Greenwald’s father, see also: Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City, 262; Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” 185; Hirsh, “Der Sigut’er historiker”: 44-46; Shlomo Zimroni, “Me-sidrei gedolei Siget: R’ Yaakov Grinvald z”l,” Maramarosh-Siget, July 1970, 1-2.

[10] It was in Hust where R. Greenwald received rabbinical ordination from Rabbi Moshe Greenwald (1853-1910), author of the biblical commentary, Arugat ha-Bosem. See: Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: 83.

[11] For additional information about the yeshiva in Undsdorf (also known as Hunsdorf), which was directed by Rabbi Shmuel Rosenberg (1842-1919), see for example: Akiva Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l” [“Rabbi Yekusiel Yehuda Greenwald z”l (A Historical-Literary Appreciation)”], in ha-Shoḥeṭ ṿeha-sheḥiṭah be-sifrut ha-rabanut, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, 185-192 (New York: Feldheim Publishing, 1955), trans. Daniella Levy, unpublished manuscript, n.d., 2.; Hirsh, “Der Sigut’er historiker”: 47.

[12] Concerning the Pressburg Yeshiva, Rabbi Moshe Sofer, his offspring, and their overall impact on Hungarian Orthodox Jewry, see: Adam S. Ferziger, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, s.v. “Sofer Family” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010) https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sofer_Family (accessed September 12, 2019) and Michael K. Silber, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, s.v. “Bratislava” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010) https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Bratislava (accessed September 12, 2019). Apparently, by the time R. Greenwald left home for the Pressburg Yeshiva in 1910, it had developed somewhat of a reputation as a place of spiritual danger and even “impurity.” As a result, R. Greenwald had to convince his father to allow him to go study there by reassuring him that he would learn Torah day and night. See: Shnayer Z. Leiman, “R. Leopold Greenwald: Tish’ah be-Av at the University of Leipzig,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 25, no. 4 (1991): 103-104.

[13] See: Leo M. Glassman, ed., Biographical Encyclopaedia of American Jews, s.v. “Greenwald, Leopold” (New York: Maurice Jacobs & Leo M. Glassman, 1935): 198.

[14] For a full-length biography of Rabbi Nobel, see: Rachel Heuberger, Rabbi Nehemiah Anton Nobel: The Jewish Renaissance in Frankfurt am Main (Frankfurt, Germany: M. Societäts-Verl., 2007). In March of 1913, Rabbi Nobel (referred to as “Dr. Anton Nobel”) wrote a generic letter of certification attesting to the fact that Rabbi Greenwald (referred to as “Leopold Gruenwald”) attended his rabbinical seminary through April of 1913 and that he has earned the right to use the official title, “Rabbi.” Letter of Rabbi Leopold Gruenwald’s rabbinical certification by Dr. Anton Nobel, 1913, Greenwald Family Collection, Columbus Jewish Historical Society, Columbus, OH.

[15] For additional information about Rabbi Nobel and his Zionist leanings, see: Adam S. Ferziger, “Hungarian Separatist Orthodoxy and the Migration of Its Legacy to America: The Greenwald-Hirschenson Debate,” Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (2015): 258, https://doi.org/doi:10.1353/jqr.2015.0007; Adam S. Ferziger, Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of Orthodox Judaism (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2015), 24; Yiẓḥak Raphael, Entsiklopedyah: 590; Getzel Kressel, ed., Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. “Nobel, Nehemiah Anton” (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1971): 1200. For an enumeration of the various yeshivot, corresponding sites, and rabbis with whom R. Greenwald learned – including Rabbi Nobel, see for instance: Katzburg, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l”: 277-278.

[16] See: Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City, 262-263; Ferziger, Beyond Sectarianism, 25.

[17] See: Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: 83; Glassman, ed., Biographical Encyclopaedia of American Jews: 198; Samuel Ephraim Tiktin, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald,” n.d., Box 1, Papers of Samuel Ephraim Tiktin, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Archives, New York, NY; Hirsh, “Der Sigut’er historiker”: 49, 51. The aforementioned article also includes biographical and genealogical details on Rabbi Tzvi Halevi Ish Horowitz, R. Greenwald’s father-in-law.

[18] Ferziger, “Sofer Family” https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sofer_Family.

[19] Rabbi Yaakov Greenwald was reputed for being not only a bookseller, but also the author and compiler of religious tomes. Perhaps most well-known of his works is the Sefer helek Yaakov, a commentary on Pirkei Avot (Chapters of the Fathers) published in Seini, Romania in 1923. See: Zimroni, “Me-sidrei gedolei Siget,” 1.

[20] Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” 185.

[21] See: Jack Greenwald, “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Received by Rivka Schiller, September 10, 2019. Email Correspondence.

[22] For more detailed information about the diversity of early 20th century Hungarian Jewry and its various factions (namely: The Orthodox, Neolog, and Status Quo), see for instance: Michael K. Silber, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, s.v. “Hungary: Hungary Before 1918” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010) https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Hungary/Hungary_before_1918 (accessed September 13, 2019). For a first-hand account of the strife and division between different sectors of the Hungarian Jewish community, as recounted by R. Greenwald, see also: Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, “Di ershte Mizrakhi konferents in Presburg” (“The First Mizrakhi Conference in Pressburg,” in Mizraḥi: kovets yovel li-melʾot 25 shanah le-ḳiyumah shel Histadrut ha-Mizraḥi ba-ʾAmeriḳah, eds. Pinchas Churgin and Aryeh Gellman (New York: Mizrachi Organization of America, 1936), 169-170.

[23] See: Raphael Patai, The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2015), 337.

[24] See: Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: 83.

[25] Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, “Di ershte Mizrakhi konferents in Presburg,” 170.

[26] Louis Bernstein, ed., Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. “Mizrachi” (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1971): 175-176.

[27] For further information about Samu Bettelheim, see for example: Patai, The Jews of Hungary, 338.

[28] Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, “Di ershte Mizrakhi konferents in Presburg,” 171.

[29] “Schreiber” is the German word for a scribe, whereas “Sofer” is the transliteration into Roman characters, of the Hebrew word meaning the same vocation. Thus, these two surnames are often used interchangeably when describing members of the said rabbinical dynasty. See: Ferziger, “Sofer Family” https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sofer_Family.

[30] Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, “Di ershte Mizrakhi konferents in Presburg,” 171.

[31] See: Ferziger, Beyond Sectarianism, 24; Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City, 264, 313.

[32] Jack Greenwald, “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Email Correspondence.

[33] I.e., what in Hebrew is referred to as “Bein ha-zmanim.”

[34] Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, Meḳorot le-ḳorot Yiśraʾel: le-ḳorot ha-ḳehilot-Yiśraʾel bi-medinot Slovaḳyah, Ungaryah, Ṭransilvenyah ṿe-Yugoslavyah (Berehovo, Czechoslovakia: Buckdruck S. Klein, 1934), 1. See also: Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” 186; Chaim Bloch, “Ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehudah Greenwald: Ha’arakhah — bi-mlot ‘arbaim shanah le-‘avodato ha-sifrutit 1908-1948,” in Le-Toldot ha-Reformatsiʾon ha-datit be-Germanya uve-Ungarya: ha-Maharam Shiḳ u-zemano: kolel ḥaye … Mosheh Shiḳ, by Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald (Columbus, Ohio: L. Greenwald, 708 [1948]), 4.

[35] Katzburg, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l”: 278. See also: Katzburg, “ha-Hisṭoriyografyah ha-Yehudit be-Hungaryah,” Sinai 40, no. 5 (1957): 313-314.

[36] Ibid. See also: ibid.

[37] See: ibid.; ibid.

[38] Yiẓḥak Raphael, Entsiklopedyah: 590-591.

[39] The major controversy surrounding Yonatan Eybeschutz pertains to his being accused by another famous fellow rabbi, Rabbi Yaakov Emden (1697-1776), of being a closeted Sabbatean – i.e., the disciple of the notorious false messiah known as Shabbetai Tzvi (1626-1676). See: Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” 187.

[40] See: Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City, 263. Among the primary sources that attest to R. Greenwald’s fame as a rabbinical scholar, even prior to his immigration to the United States, is that of the following laudatory article that appeared in the periodical, Apiryon, at around the same time when R. Greenwald made his way to America: “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald: ahad ha-olim,” Apiryon 1 (1924): 312-313. For further details regarding R. Greenwald’s treatment of Rabbi Eybeschutz in his work, see: Ben-Ezra, “ha-Rav Yekutiel Yehuda Grinvald z”l,” trans. Daniella Levy, unpublished manuscript, n.d., 3-4.

[41] The original Hebrew used for the phrase that I have translated as, “the glory of Jacob,” is “Geon Yaakov” and refers to the collective Nation of Israel, or the Jewish People.

[42] Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, “Ein shalom amar ko’.” Machzikei Hadas [Lemberg, Austrian Empire], January 26, 1912, 2.

[43] Ibid., 3.

[44] Ibid., 2.

[45] Ibid., 2-3.

[46] Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern City, 263. See also: Jack Greenwald, “50th Yahrzeit,” 2.

[47] As indicated by the book’s Hebrew title, Sefer ha-zikhronot… is a memoir regarding R. Greenwald’s travels and experiences during World War I. For a more complete citation of this work, please refer to the bibliography following the body of this paper. A highly descriptive and complimentary review of R. Greenwald’s autobiographical account may be seen in the following Yiddish newspaper article: Yankev (Jacob) Shatzky, “Yidishe memuarn literatur fun der velt milkhome un der rusisher revolutsye” (“Jewish Memoir Literature from the World War and the Russian Revolution”). Di Tsukunft (The Future) [New York], vol. 31 (1926), 241-243. I thank Michoel Rotenfeld of Touro College (New York) for sending me this book review.

[48] Leopold Greenwald, “Passover in Albania.” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 11, 1941, 4.

[49] See: Jack Greenwald, “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Email Correspondence; and James Greenwald, “Interview of James Greenwald Regarding His Grandfather, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Telephone interview by Rivka Schiller, September 9, 2019.

[50] Jack Greenwald, “Rabbi Leopold Greenwald.” Email Correspondence.

[51] For further information concerning the strict immigration quotas that were instated in the United States in the early 1920s under the National Origins Immigration (Johnson-Reed) Act of 1924, see for instance: Jonathan D. Sarna, American Judaism: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 215-216; Hasia R. Diner, The Jews of the United States: 1654-2000 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 75-76.

[52] See: “Rabbi Greenwald Passes,” Ohio Jewish Chronicle, April 15, 1955, 1; Yiẓḥak Raphael, Entsiklopedyah: 592; Sherman, Orthodox Judaism in America: 83; Silberschlag and Berenbaum, eds., “Greenwald, Jekuthiel Judah”: 81.