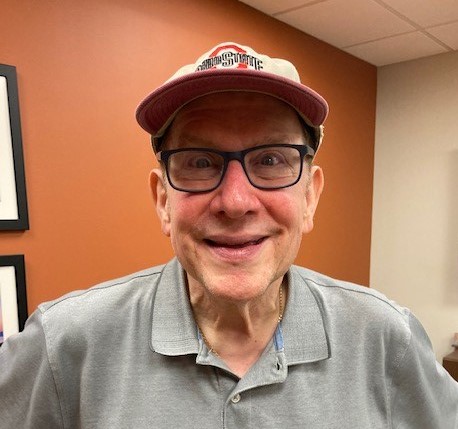

David Goldmeier

Hello, this is Bill Cohen for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society and we’re interviewing today, David Goldmeier. Today is August 29, 2022, and we’re here in the offices of Jewish Columbus.

Interviewer: So, David, let’s start with a historical background of your roots. Can you tell us how far back you can trace your roots?

Goldmeier: I can trace my roots back to my great-great-grandfather and great-great-grandmother, even a little before that, but I’m not exactly sure the names. But, if I go back, and this is on my father’s side, and I can go back to Meyer Goldmeier who was my grandfather’s grandfather. His son, Samuel Goldmeier, was my grandfather’s father, one of five brothers. They lived in a suburb, not a suburb, a town outside of Fulda, Germany. Then my grandfather, Saul Goldmeier and then my dad, Bert Goldmeier.

On my grandmother’s side, I can go back to her grandparents which were the Adlers. Her father was David Adler and my grandmother was Molly Goldmeier. My father’s side is so overwhelming in our family that I’m really not all that sure going back on my mother’s side. My grandfather, my mother’s father, passed away when I was five years old, so I have just some very vague memories of him. My grandmother, my mother’s mother, was in Cleveland most of her life, came to Columbus in her later years but we really didn’t associate that much with my mother’s family, later on, her sisters and brother in California. I was already 18 or older when I met them. I consider them my relatives and their children my cousins but they’re out in California and I’m here.

Interviewer: You said that, on your father’s side, your great-great-grandfather, or any great-great-grandfather was from Germany. On your mother’s side, your roots, do you know where they were from?

Goldmeier: My mother’s father either came here as a child or was born in America but, let’s see, he lived in Pennsylvania. My grandmother, on my mother’s side was born in America. I think her father maybe even was born in America. They came early in the 1880s and my dad came as a refugee in 1938.

Interviewer: There’s quite a difference then, between arrivals.

Goldmeier: Yes.

Interviewer: Tell me about 1938 and fleeing from Germany.

Goldmeier: Fleeing from Germany, he was 14 years old.

Interviewer: What do you know about that whole story?

Goldmeier: I know that my grandmother was the impetus for them to leave. My father could not go to school anymore because the Jewish school only went to 8th grade so he couldn’t have a profession and my grandmother said we have to leave. My grandfather wanted to stay with my uncle Maynard and my grandmother should come to America with my dad and then we’ll see if things get worse or better. If things get better in Germany, my grandmother and my dad would return and if things got worse my grandfather and my uncle would go. My grandmother informed him that both children are going to be on her arms and if he wants to stay, that’s up to him.

Interviewer: So, they saw the writing on the wall.

Goldmeier: Yes. My grandfather was a cattle dealer. I mean not like in Texas where you have a big spread. He used to buy a few beheymes. Beheymes are cows, animals, sell a few beheymes, but the Nazis started a cattle riot, started a riot in the cattle market in 1935, I believe. It was very famous. You can read about it in history. They blamed it on the Jews. They grabbed my grandfather’s partner which was his brother-in-law, Marty Adler’s father and beat him up. He was an important Jew in the community. As a matter of fact, in 1987, when we went back for a reunion trip, the city invited former residents and some of their relatives to come. A woman that we ran into lived where my grandfather’s mother lived, in the same apartment building, this is 50 years later, she remembered my great grandmother, said Adler was an important name in this community. He was a lieutenant in the army in WWI. My grandfather, also, was a decorated soldier in WWI-two Iron Crosses. For a Jew to be a lieutenant, I would say in comparable to an African American in the Korean War, when they first started to integrate the army, to be an officer. They beat him up. Then my grandparents took in clothing, wash. They bought a big washing machine because you didn’t need a license for that and they washed clothes till they came to America.

Interviewer: The story of the riot in the cattle yards is fascinating. Did you learn of any other specific examples of antisemitism as the Nazis rose in power?

Goldmeier: Yes. My grandmother and my dad were coming home from the circus once and they got stones thrown at them. Obviously, it was getting bad. They left before Crystal Nacht. They left in March of 1938 so that was before Crystal Nacht when things really got bad.

Interviewer: In November was Crystal Nacht.

Goldmeier: Right.

Interviewer: Just a few months. So, they came to the U.S. and they settled where?

Goldmeier: In Columbus because my grandmother had a sister who lived here. Her sister came here because her sister’s husband, Alex Baum, my uncle Alex, he had sisters here, and the sisters came here because the story is they had trouble getting married in Germany. This was before the Hitler times and so they came to America to find husbands.

Interviewer: Do you know the address of where your grandparents lived, or the other relatives?

Goldmeier: My grandparents lived first on Fulton Street, around 8 something Fulton Street. They shared a double with Marty Adler and his parents, my uncle Albert. Then they moved to Lilley Avenue, in Driving Park, and then they moved to Fairwood Avenue and then they lived at 1064 Euclaire Avenue when they passed away.

Interviewer: This represents the time, maybe in the late 1940s, the 40s and 50s when, I guess probably more the 40s, when Jews were still living, the bulk of them, west of Nelson (Road). You mentioned your grandparents later moved to Euclaire. That’s Bexley. Do you know when they moved?

Goldmeier: Yes. They moved in 1966. They actually lived in Columbus, in the apartments. They bought an apartment building with my dad, and they lived in the apartments between Berwick Blvd. and Livingston Avenue, not far from where we’re sitting right now.

Interviewer: That’s right. They were kind of late movers, I guess, to the east side of Nelson. Many Jews moved earlier to Bexley, Berwick and Eastmoor. It’s interesting that your grandparents and others lived west of Nelson.

Goldmeier: The synagogue was there. Beth Jacob synagogue was on Bulen Avenue, 959 Bulen Avenue. That’s where I had my Bar Mitzvah. My grandfather didn’t work on Shabbas so he needed to live close to the synagogue. The interesting thing is, most people, German Jews especially, would not go to Beth Jacob because the davening is what’s called Nusach Sefard, more of a Polish, eastern European as opposed to Nusach Ashkenaz, (spells the words). The rabbi at Beth Jacob was a world-known rabbi, Rabbi Leopold Greenwald. My grandfather’s rabbi in Germany said this is the rabbi that’s in Columbus and I think that you should go there and they became fast friends. My grandfather was a pallbearer at Rabbi Greenwald’s funeral. They were both WWI veterans on the same side, Rabbi Greenwald for the Austro-Hungarian Empire and my grandfather, the German empire.

Interviewer: What you were just talking about represents this split. Maybe split is too strong a word, but this gap between German Jews who came here and other eastern Jews.

Goldmeier: Although, the gap, see what happened, my grandfather showed up at Beth Jacob and they asked him where he was from. He said Germany. They said, my God, you’re in the wrong place. You’re supposed to be at Temple Israel.” They didn’t know the orthodox Jews in Germany. Most people thought the German Jews were Reform. In actuality, most Jews in Germany were orthodox or associated with orthodox synagogues if they associated at all, outside of Berlin and maybe Hamburg, the two big cities. Most Jews were associated with orthodox synagogues. Fulda is about 60 miles east of Frankfurt which was Rabbi Hirsch and later, Breuer, which is the Jewish community in Washington Heights in New York today and still going strong.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about your parents, the names of your parents?

Goldmeier: My dad’s name was Bert, it was changed from Sigbert when he came to America and my mother’s name was Helene.

Interviewer: Your mother’s maiden name?

Goldmeier: Schwartz.

Interviewer: They lived here in Columbus.

Goldmeier: Yes. They met at Ohio State. My dad was in pharmacy school and my mom was a freshman and they met, and they got married. Actually, my dad had graduated pharmacy school when they got married.

Interviewer: When they were just married, around that time, where did they live?

Goldmeier: 783 South Cassingham (Road).

Interviewer: They were in the Bexley area, in Bexley. What year did they get married?

Goldmeier: 1949.

Interviewer: Do you know where they lived before that?

Goldmeier: They lived, I think, originally at Main (Street) and Ohio (Avenue) because my grandparents owned the building, and my grandparents had the grocery store downstairs and they lived in apartments on top. Then my grandparents had an apartment building later in Driving Park on Lilley Avenue and Columbus Street, the corner. I think my parents, I think they lived there for a year or so and then bought the house on Cassingham.

Interviewer: So there was a grocery store at or near the corner of Ohio and Main and your grandparents…

Goldmeier: Owned it.

Interviewer: What was the name of that store?

Goldmeier: I think it just may have been Goldmeier’s Kosher Market, I’m not sure.

Interviewer: It was kosher meat?

Goldmeier: Oh, my grandparents, yes, yes, my grandfather, they wouldn’t own anything other than that.

Interviewer: We always hear about Martin’s, of course. We don’t hear that much about Goldmeier’s. Do you know anything about that?

Goldmeier: Sure. They had that store. They bought the store in 1944. It was probably a grocery store before that. My grandmother had some connection with the Oscherwitz. They made the meat, salami, deli, and they were in Cincinnati. They were shoe-string relatives, so to speak. So, they could get their meat from there. They had that store till 1954. They sold it to Sutton and Weston, Bernie Weston of blessed memory, his father was one of the partners. It wasn’t kosher anymore.

Interviewer: It was kosher when your family had it.

Goldmeier: Just a regular market, then my grandfather kind of retired for a few years but it was really too early to retire so he bought into the original Bexley Kosher Market which was, well today it’s where the Mikvah was, that building where the Mikvah and Bob Goldstein’s law office is.

Interviewer: That’s on East Main Street.

Goldmeier: East Main Street in Bexley. Right, it was Knolls Realty for a while, right next to Johnson’s Ice Cream. Johnson’s owned the land. He bought in with Emil Haas who already owned it. Another partner passed away, so my grandfather bought in. Emil was also kind of, he was kind of related as well, though, again, my uncle Alex.

Interviewer: Again, this early history of your parents and grandparents seems to fall within the general idea of the Jews living west of Nelson until, maybe post war, and then making the jump to Bexley, Berwick, Eastmoor.

Goldmeier: All the synagogues moved. The synagogues were at Donaldson and Washington. The Bryden Road Temple was the Reform temple. They moved, so people moved with them.

Interviewer: I guess the question might be did the people move before the synagogues or did the synagogues move first and then the people followed. I guess that’s probably an academic question.

Goldmeier: Yeah, it was both. The people moved first obviously. I shouldn’t say obviously. The people moved first.

Interviewer: So, you were born what year?

Goldmeier: 1952.

Interviewer: At that point your parents were living on?

Goldmeier: South Cassingham.

Interviewer: Between Main and?

Goldmeier: Between Mound and Astor.

Interviewer: Yeah, in Bexley. What do you remember of your early years?

Goldmeier: Well, I was in the first class at Torah Academy. We started there in 1958. I went to kindergarten at Montrose. I would say that Torah Academy, it was (I’m trying to think of the words for a minute. I’m usually not at a loss for words.) The idea of Torah Academy was bigger than the school itself. In other words, going to school there was just like going to school. The idea of having a school where you had half a day Jewish studies and half a day secular studies, that was an idea that was spreading throughout the country and in Columbus as well. For me, I would say I got a first- rate Jewish education. My secular education, I could have used a little bit more help. That was just me. A lot of people did very well with just half a day. The Jewish education was first-rate, really it was just outstanding. By that time, we’d moved to Berwick. We lived at 2611 Sonata Drive by the time I was in second or third grade. Me, I was lonesome. Most of my friends, all the people I went to school with, lived near the school in Bexley and Eastmoor. So, you know, when you come home you don’t have your buddies to play with. We had a small class, eight people, six guys and two girls. I was lonesome. I was the oldest of four. I did have some friends in the neighborhood, Marvin Zeldin, Alava Sholom, and Jay Waitzman but it’s not the same as the guys you go to school with. So, when I left Torah Academy in 8th grade, because that’s as far as the school went, I ended up going to Johnson Park for junior high because in those days 7th, 8th, and 9th grade were junior high, even though 9th grade was the first year of high school. That’s when my deficiencies in secular education became apparent to me. I was really fortunate to have Marvin, of blessed memory, kind of shepherd me around.

Interviewer: Marvin?

Goldmeier: Zeldin, Marvin Zeldin kind of shepherded me around. Everyone liked Marvin. He was a good guy. Then I got into BBYO. I got into AZA in 9th grade. Then, my world started to open up because I got to 10th grade at Eastmoor and I see the guys from AZA. My guys are 11th grade, 12th grade. I always say I learned about Judaism at Torah Academy, but I learned how to be a Jew when I got into AZA, what it means to be a Jew, what it means to go out with a Jewish girl. All those things I learned from watching the other guys and seeing what they did. It’s just something that sticks with me till today. I can tell you, I was thinking about a couple of stories, just to give you an idea. So, Capital AZA is playing Heart of Ohio AZA baseball over at the Jewish Center diamond 1. I’m watching. Older guys are playing. They only played seven innings, the bottom of the sixth, we’re up. A guy hits a ball and we’re losing. Capital is losing but the guy gets a base hit and someone in the outfield is trying to throw it to the catcher who was one of the Berliners. I can’t remember which one. Anyway, the ball gets by the catcher. He runs past me, I’m watching, and knocks me over. So, as he’s running after the ball, I grab his leg, he falls down, everyone scores, now we’re winning. After the game we won, this Berliner comes and says, “I want Goldmeier.” He didn’t want to kiss me, I can tell you. It wasn’t to kiss me. Dave Engelman, as they say in Yiddish, a shtick holtz, he was a piece of wood. He was like 5ft. 8 inches and broad. He says, “You’ll have to go through me first.” Arnie Levine, who interestingly enough was in town a few weeks ago and asked about me. This was back in 1968. He asked one of my friends, Barney Greenbaum, about me. Barney told me. Arnie said, “You’ll have to go through me too.” All of a sudden, I’ve got this team of guys saying, “Look, you want him, you got to go through us first.” The fact that I’m sitting here talking to you today means that I didn’t get cracked on the head with a baseball bat by Berliner. That was the brotherhood. That was the camaraderie. That’s where I learned you have a special camaraderie there that you don’t have to earn. With your non-Jewish friends, you kind of have to earn it because it’s not just there. You have to earn it. That could be from being kind, it could be from having the same interests, whatever. With your Jewish friends, you don’t have to earn it. It’s there until you screw it up and you can screw it up and lose it, but that’s my experience. Then, in 12th grade, a lot of my buddies left. I was friends with a lot of older guys, and I was not looking forward to 12th grade. Again, I was lonesome, a little bit lonesome. Then I started dating a girl, Debbie Shiff, related to not the Schiffs from like Herb Schiff who’s on the wall over here, but the Tuckermans, the Thalls. She was related through her mom to them, and I wasn’t lonesome anymore. Then, it was a great year. We got quite serious until we weren’t. Sometime between freshman and sophomore year, we broke up.

Interviewer: Of college.

Goldmeier: Of college, yes. We broke up. Looking back, regretfully, I was very unkind in the breakup. She’s done very well. She had no trouble finding other boyfriends, got married to a nice man I knew from Hillel at Ohio State, Michael Kuhr, a smart man, a nice man, and I’m happy for her. I see her stuff on Facebook. She’s doing very well. I was going to talk about my wife. Go ahead.

Interviewer: You talked about you were 16 or so in AZA and you talked about the brotherhood. You felt you belonged with your fellow Jewish boys. You were in high school at that point, at Eastmoor, and as I remember at that point there were Jews, other whites, and there were Blacks. It was somewhat integrated, late 60s, what was that mix like?

Goldmeier: In looking back, you associated, again, mostly with the Jewish people. We ate lunch mostly with Jewish guys. There were some people, like Steve Georgeff, Orb was his nickname. He was not Jewish, but he associated with a lot of Jewish guys. We all knew him. He hung out with us also. Mostly, in the lunchroom, Blacks ate in a certain area, Jewish guys, see what I did was, in 11th grade there was a fellow by the name of Mickey Press, of blessed memory. Mickey was a very good-looking guy. He was a lot like Steve McQueen. Steve McQueen doesn’t talk much. He didn’t like to talk much. I sat next to him for lunch. I picked him out for 11th and 12th grade because I knew there would be a lot of girls sitting around him. He was happy to have me there. I didn’t want to talk to him really. His girlfriend was Karen Rosenfeld, Mayer Rosenfeld’s, who used to run the Jewish Center, daughter. That was for me. I figured out this is who I want to sit next to. It’s a good place to meet girls.

Interviewer: How did the Jews and non-Jews get along or not get along?

Goldmeier: The ones who, the guys, I’d say, who were in music got along really well because there were a lot of Jewish people in music, a lot of African American people in music. They got along great. I had a friend of mine, Julius Hunter, who is now, I believe, a Federal Judge, African American. When our friend, Marvin Zeldin passed away, I posted it on the Eastmoor Facebook and Julius said, “You know Marvin was such a nice guy.” He said, “One of my great times I remember is Marvin and Julius and myself and David Schottenstein went to the old Crosley Field before it shut down in 1970. We were seniors in high school. We went to the old Crosley Field to watch the Cincinnati Reds play.” He remembers that 50 plus years later, one of the best times of his life. Outside of Julius, I would say I didn’t really have a lot of African American friends or the non-Jewish friends, some of the guys in the neighborhood, but still, I would say, for myself, not that many because I was associated with the synagogue. I had friends in synagogue. I spent time in synagogue. It’s hard to generalize but I would say that the guys who were in music really found each other. They got along great. Music is a great way to put people together. For me, I was in sophomore chorus, and at the Christmas program, the teacher said, “Just mouth the words, but you know what, keep selling that candy.” We sold candy to raise money.

Interviewer: So, the teacher was sensitive to religious differences?

Goldmeier: No, he was sensitive that I couldn’t sing. He just said, “Mouth the words.” He was sensitive that I couldn’t sing.

Interviewer: Oh.

Goldmeier: So I wouldn’t be one of the ones that associated so much because of me, but the people that did, still and, even to this day, they’re still friends.

Interviewer: You graduated high school in what year?

Goldmeier: 1970.

Interviewer: Do you recall much racial tension?

Goldmeier: Well, we had the riots in 1969. First, in 1968, we had a walkout when Martin Luther King was killed. In 1969 we had a riot, in February of ‘69, because some stuff was put in the trophy case that was controversial and the principal took it out and then the Black kids didn’t go to class. When lunchtime came, everyone has to eat lunch and that’s where the riot broke out, was in the lunchroom. Then three days later, four days later, we came back to school. Then in 1970, again, myself, Julius Hunter, David Schottenstein, Marvin Zeldin and his brother, Howard Zeldin, the five of us went to Cooper Arena to watch the District Finals and Mohawk got beat that year. Mohawk was an all-Black school, today Afrocentric, and then they took out their frustration, after the game, on us, even though we’re with a Black guy. It didn’t make a difference.

Interviewer: You were with a Black guy.

Goldmeier: Yeah, Julius Hunter.

Interviewer: You still were targets.

Goldmeier: We still were targets, yeah.

Interviewer: Let me just ask, any other memories of your high school years in terms of Jewish institutions?

Goldmeier: Oh, I could tell you, we could sit here all day. I’ll tell you another story. Rob Cohen and I, I don’t know if you know Rob. He’s an immigration attorney in Columbus, Rob Cohen and I are in charge of the Beau Sweetheart Dance. Rob is a year older than me. He’s 12th grade, I’m in 11th grade. This was the AZA, BBYO dance. My date, the set up was from Zanesville. Girls from Zanesville, the guys associated with at one of those dances. The parents wanted them to meet Jewish people, so they came to Columbus. I didn’t know her. I did know Vicki Rogovin who I’m still friends with. She lives in Columbus, Vicki Dopkin. She just had twin grandchildren. This girl, Marci, she heard through the grapevine that supposedly I wasn’t cool enough. She’s not coming in. This was two weeks before the dance. I’m in charge of it and I’m running around looking for dates. You have to understand that I’m in 11th grade and, you know, I’m not exactly first round draft choice and A and B girls have been taken and I’m looking for the Cs, and now I’m looking for the Ds. I’m unable to find a girl. It was also kind of embarrassing for them maybe like a week before. So, I said “Well, I just not going.” Rob says to me, “You’re going.” Go upstairs in the old mimeograph room.” Rob Cohen, myself, Neal Barkan walks in. He said, “Downstairs there’s someone who’s looking for a date.” We’re like on the third floor of the Jewish Center, some girl looking for a date. It turns out, later on in life, she came out as gay. It was someone who just wasn’t appealing to me. Like I say, I’m no first-round draft choice either but they said, “You’re going to the dance.” I said, “No, I’m not going to the dance.” Rob says, “Neil, hold him down.” Neal is holding me in a chair. I can’t leave. Rob goes downstairs and he calls upstairs. He goes, “I found out there’s a girl who still doesn’t have a date and wants to go.” I said, “What’s her name?” He tells me. I said, “Rita Bernstein, well you know Rita’s the first girl I ever took out. I would love to go with her.” So, I call her, we have a date. I just saw Rita last week in Chicago at a wedding. Rita is a sister to Irv Szames, a lot of people know.

Interviewer: He was active with Martin’s Foods.

Goldmeier: Then, later he owned Bexley Kosher Market, right. We were at her great nephew’s wedding in Chicago. So that worked out. There are a few BBYO stories. We could sit here all day and talk about that. I started Ohio State in 1970. One of the reasons that I broke up with Debby is I’m like this yeshiva bocher who went to Johnson Park and then Eastmoor, but then Ohio State, I’m free and I’m what the Amish call Rumspringa I’m not sure if you’re familiar with the term. That’s part of Pennsylvania Dutch where they let the 18, the 19 year olds, they say go out into the world and have a blast.

Interviewer: Their first 18 years they were immersed in the Amish community, very insular. Then at 18 they get a chance to break free and see what the outside world is like.

Goldmeier: When I got to Ohio State in 1970, I wanted to do some Rumspringa and I found some older Jewish guys who were experts in Rumspringa and I fell right in.

Interviewer: You mean they were partiers?

Goldmeier: Oh yes, we lived a fraternity life without going to the fraternity. Yes, whatever like crazy stuff, things like that, I was up for it.

Interviewer: Just to be clear here without going into detail, are you basically talking about drugs, sex and rock and roll, with some beers in there?

Goldmeier: Substitute the beers for the drugs because my dad was a pharmacist, so I was kind of warned off drugs early on and also I worked in a drug store. Everything else was good and I’m still going to Hillel for Services. I’m still keeping pretty much kosher meaning I wouldn’t eat any non-kosher meat. I graduated in 1974 and I’m still not sure what I want to do with my life so I hang around school for another year. One of my friends, Mike Siegel says to me, “There’s a dance at the JCC why don’t you come along to the dance?” Sure, Mayer Rosenfeld is calling square dancing. I know it’s hard to believe, Mayer Rosenfeld, a Jewish guy, calling square dancing. He’s an expert at it. There’s a girl that wants to dance, Sherry Silverman today. Her name was Sherry Alper back then. She wants to dance with Mike Siegel. Mike is standing with me. He goes “Well, my friend, Goldie over here, he doesn’t have anyone to dance with.” Sherry just met my wife who is all of four ft. 10 ¾ inches. You go below 5 ft. you go to the 3/4 issue, the quarters.

Interviewer: Let me understand, she met your wife?

Goldmeier: Yes.

Interviewer: The woman who would later become your wife?

Goldmeier: Yes.

Interviewer: Okay. The woman who would later become your wife was also at the dance?

Goldmeier: Yes. She met Terry and Sherry is not a shy person. She takes Terry, who’s like I say under 5ft., maybe 100 lbs. and throws her at me saying, “Goldie is taken care of. You’re coming with me.”

Goldmeier: We started dancing and start talking and Terry’s mother was a survivor of Auschwitz. Her father was one of Winton’s kids. Winton was a stock broker in the 1930s, non-Jewish stock broker. They did a movie about him. He was interviewed on 60 Minutes. He saved over 100 children, Czech children, after the Anschluss. The Anschluss was in Austria, after the Germans marched into Sudetenland, in 1938 and 39. He came over to England and saved them. We didn’t know any of this at the time, by the way. It wasn’t until my father-in-law passed away, I saw this thing on 60 Minutes and we knew about Winton and then I saw the film. I looked his name up. It was on the internet that he was one of those kids. He had his mother sign for him there. He was raised in a Methodist orphanage. They have two girls, my wife and her twin sister, Debbie. They had no practice at parenting, zero, because my father-in-law was 10 years old, came back to Czechoslovakia after WWII. Both his parents survived. They survived Terezin. In 1948, Czechoslovakia was the last country to go communist, so his parents sent them out. They really didn’t have experience. Terry was not very happy at home. Again, she turned 18 and saw there was a bigger world out there. We connected because of the European background I had. My grandparents liked her parents. They ended up having a connection. My dad, my parents too, again, my grandparents were 40 and 37 when they came over. They connected a little bit differently. We had a whirlwind relationship. I went to Florida to work for Gray Drug and ended up as a store manager there on 41st Street in Miami Beach. I was 23 years old. Before I left, I said to Terry, “Look if we still feel this way in a few months apart, let’s get married.” We were engaged in November, 1975 and we got married in June, 1976.

Interviewer: Terry, her maiden name?

Goldmeier: Was Steindler. It’s interesting, she just gave me a card for our anniversary, 46 years in June. The card says, “First came love,” a picture of a few people in love, “Then came marriage,” this is all on the first page, the bride and the groom and the cake, standing there. Open the card and it says, “And then all hell broke loose.” That is our relationship. I know some people say their husbands and wives are best friends. We’re partners. We’re life partners. We had an insurance business together for almost 20 years. We have three 37-year-old children, Steven, Melissa and Jordan. You have to be partners to raise three kids all the same age. We have the same sense of humor. We’re romantic partners, of course. Best friends, you can lose a friend. You can’t lose a partner. You can say, well they’re not my best friend anymore but they’re friends. Well either you are a partner or you’re not. We do have different interests. I was thinking, for example, I’ve been out to Las Vegas maybe 40, 50 times and she sometimes comes with me. She thinks Las Vegas is to go out to the pool, get a tan, stand on her head in the water for 40 seconds. It scares me when I watch her do this. Then, but most importantly, to cadge my free drinks I earn shooting dice but mostly playing poker. She sits in the poker room and waits for the drink list. She can drink pretty good for someone who weighs about 100 lbs. We have different interests. She’s at the swimming pool. She’ll be at the Jewish Center today three, four hours doing Yoga, swimming, all that. She likes the outdoors. I’m more of an indoors person. We love each other. We have the same sense of humor. We have this deep connection that we can understand each other because of our backgrounds. Our backgrounds, we understand how the other one was raised, even if there’s things we don’t agree on. For example, I told you I was working when I was in school. When you’re at Ohio State, when you’re in school, you have to study or you can play or work, but you can only do two out of those three and be successful. Well, my dad told me, “There’s no way I’m paying for an apartment for you to live at Ohio State.” When my dad was in pharmacy school. He’d been through WWII already as a medic. He said in his mid to late 20s he lived with my grandparents and on Sundays and other free time he worked in their store. Consequently, when he graduated pharmacy school, he did not have enough intern hours. He was short intern hours. He had, in those days, to work 2,000 hours in a drug store before they gave you a license. He was working for his parents some while all of his other buddies graduated school and they’re working as pharmacists. He had to work what they call “the cigar counter.” He was doing the truck, helping unload trucks and didn’t regret it, never blamed his parents. He had to get those hours in and was getting paid a lot less than any of his friends. Well, that man was not going to pay for me to live at Ohio State when I could live at home in Columbus, Ohio. That was just not going to happen. If I wanted to live on campus, I had to work. If I wanted to play, I had to play. My grades in school consequently suffered a little bit because of that but it all turned out. I managed a drug store. We came back to Ohio, by the way, in 1980 because we thought, if we’re going to have a family, we’d want to live in Ohio. I came back and I did some accounting work. I had a degree in accounting. I was comptroller for a company called National Waterbed Warehouse. Then three children come along in 1985. Our oldest son, we adopted. Two weeks later, found out my wife was pregnant with twins, and they’re born early so there’s 27 weeks between them. Now I’ve got to do something where I can make some money, either have my own business or I can work commission. I went to work for Allstate Insurance and then we opened up an agency right where the woodworker store used to be, Cassingham and Main, where today the Penn Station is. We were downstairs. We made a great, good go of it.

Interviewer: Tell me, where were you and your wife, Terry, and now your kids, where were you living?

Goldmeier: At first, we lived at 635 Montrose. We bought the smallest yard in Bexley. It’s the one house that’s between Main Street and the alley that runs behind Main Street. We bought that house before she gave birth because I didn’t want a realtor seeing that we got a little one and that she’d go like this and they’d know we’ve got to move from our apartment we were living in, where my grandparents lived. In those apartment buildings you’ve got a two-bedroom place. I’m going to have three children. That wasn’t going to work. So, we lived there, and then in 1989 we bought a house at 645 South Cassingham. Here I am living a block away from where I grew up at 783 S. Cassingham. We lived there until 2019 and we moved to apartments on Parkview, Parkview Arms.

Interviewer: Your children, where did they go to school?

Goldmeier: Originally, they went to Torah Academy and then what happened is we ran into a rough patch at Allstate. Hurricane Hugo in 1989 and then Andrew in 1992. Andrew wiped out every penny of profit Allstate made since 1945 in Florida, every penny. They said, we’re going to be very careful in taking risks, especially in Florida, but all over the country. They put a lot of limits on our new business that we could write. Well, that hurts your income. You can’t write new business. You’re just doing renewals. You can sell life insurance, but Allstate is not that well-known for life insurance. We’re mostly a property, casualty business. I went to Torah Academy and said, “Look, we’re just not going to be able to do the tuition this year.” The person running it, not the principal, Rabbi Millen said, “I’ll work something out.” I said, “Rabbi Millen, I happen to know that they did not renew your contract for next year.” It was true but we didn’t know is they couldn’t find anyone else with his qualifications to take that job, so they renewed it, but right towards the end. We’d already made our decision. The guy who was running the scholarships said, “No, we’re basing on what you made last year.” I said, “But that’s not going to be this year.” “No, too bad.” We sent our kids to Montrose and then they went through the Bexley system. I think Steven went for two years. Melissa and Jordan went for one year. We held them back because we went when they were supposed to be born. They were supposed to be born the middle of September, not August 1. September was the cut off, so they went based on a recommendation from Anelyn Baron. Anelyn taught the pre-school at the JCC and she’s a Shkolnik originally. That’s a well-known name.

Interviewer: In the 80s and 90s were you members of a particular synagogue?

Goldmeier: Yes. We went to Beth Jacob. What happened is, as my kids got older, because they didn’t go to Torah Academy and everyone else did, and everyone lived in Bexley and we lived in Berwick, they were kind of ostracized.

Interviewer: Who was ostracized?

Goldmeier: My children. They had friends who did go to Torah Academy and Agudas Achim, so in the late 90s, we switched over to Agudas Achim. When the Main Street synagogue opened up, we lived right around the corner, and we ended up going to Main Street. Terry and I still belong to that.

Interviewer: Tell us about these later years, 90s and 2000s.

Goldmeier: Back in the 1980’s, there was a Jewish social club that is here in Columbus. A lot of people don’t know about it. You’re looking at me quizzically. It was kind of secret. It was a place where you could walk in, it was guys only. You could walk in and starting at noon, in those days, in the mid ‘80s when I joined up, starting at noon through maybe 1:00 a.m. there would be gin rummy games, poker games, 4 ½ bookmakers. It was a place to go blow off some steam. Plus a lot of Jewish guys, people I knew from high school, people I grew up with, some of the older guys and it was a place where I had a lot of fun.

Interviewer: This is an actual geographical place.

Goldmeier: Yes, a geographical place.

Interviewer: Is it still around today?

Goldmeier: Unfortunately, about 5 or 6 years ago we closed because people passed away. You have a casino in Columbus if you want to play poker. You can do sports gambling on line.

Interviewer:Can you tell us where this place was without getting anybody in criminal trouble?

Goldmeier: I can tell you where originally it was, on Main Street near Whitehall, then later on in Reynoldsburg. It was a great time. Some of those guys I go to Vegas with. You know what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas. We had a lot of laughs. Just to give you an idea, we got thrown out of Barbary Coast because one of the guys was counting cards.

Interviewer: Barbary Coast is?

Goldmeier: A casino, it’s now the Cromwell. Right on the corner there you have Caesars Palace and Bally. You have the Bellagio which used to be the Dunes and now the Cromwell which used to be the Barbary Coast.

Interviewer: In Las Vegas.

Goldmeier: In Las Vegas and they cancelled our dinner reservations on top of it.

Interviewer: Did this place in Columbus that was the Jewish social club, did it have a name?

Goldmeier: Yes, but I’m not going to talk about it. People who read this who will know, will know about it.

Interviewer: Was this place, in general, not known to the wives?

Goldmeier: All the wives, they all knew about it. All the wives knew about it, wives, the girlfriends, everybody knew about it. Everyone knew about it. Of course, you don’t come home, you go to the club. You go at noon and then you don’t come home till midnight. Of course, they know. I mean they had to know about it because otherwise they’d think you were out with a girl. There were some non-Jewish people there too. It was mostly Jewish guys. I’ll give you a story. One of the guys who just resembled the mush (?) from the Bob’s Tale. I don’t know if you saw the movie with Robert De Niro. This guy could never make a good bet. One year he went 0 for 29 in college basketball. Imagine betting on 29 games and missing every one of them. He walks into the club, runs in, says, “I got the bet, I got the bet of the decade.” This is before the internet. I got a guy who told me the weather. I got a weather guy in Detroit. I called him up and it’s going to be 20 below zero and the Bears are playing the Lions and over under is like 40. Over under means total points scored. There’s no way they’re going to score 40 points in this kind of cold weather. Nobody will be able to pass. They’ll fumble, this and that. This is the bet of the decade. Someone said to him, Z was his nickname. “Z how much money did you put down?” “Oh like $250.00.” He said, “Z, they play in the Silver Dome. They play inside in Detroit.” This is nothing compared to, this guy, they used to go on a golf trip every year and once a year at golf he hit the ball and the grass came up. One of the guys from the golf course said, “Sir you took a divot.” He goes, “I never took anything in my life and I resent that.” This is a guy who when he retired from work and moved away had over a 100 people come to his dinner at the TAT. This was the guys I used to hang with. Before I was hanging with them, once they got a slot machine in Vegas that was paying off. It changed the payoff dollars, but it was still taking quarters. They guarded it for 24 hours and then sold the rights. (Laughs.)

Interviewer: So, in your mind, is this kind of a more modern version and a version for older Jewish men that’s a continuation of your AZA days?

Goldmeier: I would say yes. We still have a weekly poker game, a lot of guys that I grew up with, guys who are like my brother’s age. I walked in and talked to Toby about them. We had non-Jewish guys too. One thing is, growing up in Columbus, and this is something being the one the orthodox community that we had, that a lot of other people didn’t have, is we associate with non-Jewish people as well. We just went to, our next-door neighbors had a party on Shabbas, Shabbas afternoon. Terry and I walked over to our old next-door neighbor’s house when we lived on Cassingham. We’re friends with them. You grow up in Columbus, you learn to be friends with everybody. Not only that, when we grew up, it really, after Torah Academy, Torah Academy was biased against non-orthodox Jews, non-religious Jews. They would teach you that, the teachers. The teachers, we have to think about where did we get our teachers from. Most were survivors, people who had come from Israel or couldn’t make it there and came to Columbus and taught. They had this bias. When you got into high school, into BBYO, it didn’t make any difference where someone went to synagogue or didn’t go to synagogue. That made no difference. One of the reasons I think I got accepted is, as soon as I got in, because I was unique, the first class at Torah Academy, AZA, Goldmeier you take the Religious Committee. You’re in charge of that. I was probably the only guy in Columbus that could read the Torah and the racing form at the same time. I will tell you though that we have a really nice modern orthodox community here in Columbus, Ohio now, a lot of professional people, a lot of people who are associated with the hospitals and doctors and engineers and attorneys. We have a nice group of people and Intel is going to even bring some more in that are well educated in secular knowledge as well as Jewish knowledge. We do have a group of people though that aren’t as well, nice people, don’t have the secular knowledge but they like Columbus because I think they’re acquiring secular knowledge. It’s not like New York. The orthodox community is a very separate community in that, Terry and I, we were in Miami a few weeks ago. I told you I helped interview Ben Ferencz, 103 years old, the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor. We sit down with people, they’re from Baltimore. Oh, do you know this person? This person lives in Columbus. We know this person from Chicago. We were in Chicago last week and, as I told you, for the wedding. There were people who said, “Oh yeah, I heard you were in Miami, so and so sent me a picture of you guys.” So, there’s a group of people that are in the orthodox community that associate with each other through other people. It’s not just a Jewish geography with people that know each other. Then we have, as I say, a nice group of people here in Columbus are moving in that I know and probably non-orthodox as well.

Interviewer: You obviously have a strong Jewish identity. You also are a man who goes out into the rest of the world.

Goldmeier: Yes, for sure, I mean, yes that’s a big part of it, that’s a big part of living in the rest of the world, being friends with everyone. One of my college roommates was from Delphos, Ohio, one of the quote-unquote, degenerates I used to hang around with. He was Jewish but he and another family were the only Jews in Delphos, Ohio. In the Spring break I would go up and help them in the egg processing plant they had there, and work there. I will tell you that is hard work, working in an egg processing plant. We have one in Columbus, outside of Johnstown, Ohio. That is hard work. I know some of the people, not Jewish, who work there, that I worked with at Safe Auto Insurance which is where I worked the last 15 years in the insurance business. They said, “Yeah, the work is about the same. It hasn’t changed in 50-some years.” Again, he had his whole life to associate with other people who weren’t Jewish and that helps navigate me as well. As I say, because in Eastmoor most of the people I associated with were Jewish but that helped me as well.

Interviewer: How optimistic are you about the future of the Columbus Jewish community?

Goldmeier: Much more optimistic than I was about a year ago when they announced that Kroger was closing its kosher section and some other things went down. I can’t remember exactly what else. We have Columbus Community Kollel which is very good as far as bringing people to Judaism. It’s a place for people to study. The rabbis are extremely knowledgeable. Rabbi Morris, who is the Rosh Kollel is extremely knowledgeable, also in secular things. He is a non-practicing CPA because where he went to school in Ner Israel, they said, if you don’t like the Kollel business, you still should do something, have another job, have something else. If the Jewish things don’t work out when you graduate, he’s about my age, a few years younger than me. He’s very knowledgeable. He talked in our synagogue about Jonathan Edwards. Remember Jonathan.

Interviewer: The singer?

Goldmeier: No, the preacher from the 1700s, Cotton Mather, going back to those days.

Interviewer: You were pessimistic about the future of the Columbus Jewish community?

Goldmeier: Yes.

Interviewer: A year ago because Kroger was dumping its kosher section?

Goldmeier: Yes, also, it just seemed like there were some people who moved out of town. The restaurant closed. Jay Schottenstein used to have a restaurant. By the way, I didn’t mention, I worked at Schottenstein’s through high school as well. That was also one of the things that Jewish kids did. I happened to work with Jay, and I will tell you he got no special treatment when he worked there. He worked on the floor with me. If something wasn’t in stock, he’d have to ride the freight elevator like the rest of us, the south side, the original Parsons Avenue. I was looking at that, the restaurant closing. I said what’s going to bring people to the orthodox community but then I see there are people that are moving here, that there are a lot of things that say, okay, maybe we don’t need the kosher restaurant right now. We’ll figure out a way to get kosher food in here. We like living in Columbus because unlike, if you live in Baltimore, for example, in your part of the orthodox Jewish community, everyone knows your business. Your neighbors know what’s going on. They’re looking in, your children, everything you do. If you have a child that doesn’t like the school or something, it’s a bad mark on you. Let alone you live in New York. Columbus is different. People don’t care. People accept you here. We’re happy to have you here. It’s a lot different. People feel freer in Columbus. Also, as I say, the neighborhood, the rabbis, it’s not top down where I’ll give you an example. In Brooklyn where people were hesitant about taking vaccines, one of the rabbis wrote a letter you’ll see on the internet. It said, “It’s not your business. You need to be doing is listening to doctors and, even if one doctor says don’t take it, you still need to take it.” By the way, what are you even bothering yourself with vaccines for? You don’t even know the proper blessing to say when it turns from summer to winter. You think you know something about medicine. Your body is not yours. It belongs to God.” It’s all on the internet. I got my vaccines. I’m not talking about I’m being anti-vaccine, but your thinking about it. I believe is taking away from your time for studying Torah. This is in Burrough Park. It’s a top down. Here, things that are done, are bottom up. Things people are doing, charitable works and someone has a baby and people are bringing meals. That’s not something in the community everyone has to do, people are doing it. So, it’s a bottom up which I think works better.

Interviewer: The fact that you grew up in Columbus when almost all the Jews lived in Bexley, Berwick or Eastmoor and you, of course, know in the last 50 years there’s been a lot of dispersal of Jews throughout all of Columbus including, well obviously, New Albany where there didn’t used to be any Jews at all 50 years ago, or Arlington, many other places. What’s you view on that? Has that been a good thing, a bad thing?

Goldmeier: I think it’s probably, in the long run, it’s something that’s not sustainable for those families. In other words, it doesn’t mean, I’m not talking about New Albany. New Albany is different because you have Rabbi Apothaker. It’s not Rabbi Apothaker’s synagogue there anymore, but Temple Beth Shalom, is that it? Then you have Chabad. So there, you have community. You have infrastructure, community infrastructure. If you live as a Jew somewhere in Worthington, and you’re the only one on your street, or Westerville, and you’re the only one on the street, it’s just not sustainable for your families, I don’t think, unless you have a connection, unless you know you’re driving to temple or you’re going to temple every week, then maybe. If you live in a neighborhood without Jews, or other Jewish people, it’s just not sustainable, I don’t think. I don’t know though. I have a degree in Accounting.

Interviewer: In general, you say you’re optimistic about the future?

Goldmeier: Much, much more so than I was six months ago or eight months ago or nine months ago. Yes, there are a lot of things going on. As I get older, I’m not involved in them anymore. I’m not part of that, but there are a lot of people. Here’s what I will say is different. What is different is that when I grew up and we’d raise our children in that. The synagogue was a big focal point of the Jewish community, the synagogue and the JCC. Today, a lot of people come to the synagogue. They come, but they’re there for prayer. They don’t necessarily want a leadership position. Maybe they’re leaders at their work. Maybe it’s just something they’re not interested in. They’re also not always that interested in getting to know the older people. They have their group. I don’t mind that. As you can tell, we know enough people plus my wife is a candy lady at synagogue, so, she gives out, the kids all come to her. They say good Shabbas. She gives out candy to everybody. She buys her candy. Sometimes the Kollel rabbis will go back to Baltimore or New York, and they got ten bags of lollipops for her a few weeks ago. She’s the candy lady so she keeps herself active, and through her, I know a lot of younger people because that’s very important to her, the little kids. By the way, I don’t know if I told you, we have two grandchildren in Baltimore, Maryland. Our boys aren’t married. Our daughter is married, twins again, three generations of twins, twin boys. They’re four years old. My one son is an attorney in Columbus. He used to work for the public defenders for the state so everyone he was working with was already in prison. I’ll brag on him for a minute. He’ll be mad about this. You can go on YouTube and see that he was one of the youngest attorneys ever to appear before the Ohio Supreme Court. He does not like going to court so what he’s working on is a project for indigent juveniles in New York, trying to make sure that the money that they get is spent correctly and gains the most bang for the buck for money from the government that’s going to defend them. It’s a project funded by Southern Methodist University. He’s in Columbus. He was in New York for a minute, but then he figured everyone said you don’t have to live in New York to do this. He actually worked for the Bronx Defenders for a while. So, he does that. My other son is moving to Portugal tomorrow. He’s a computer guy. He’s written three books. He’s working on number four. Excel is his specialty. He was living in Brooklyn. Again, he’s a digital nomad. Portugal is relatively inexpensive. He’s not married, and he can do whatever business he does in Brooklyn, he can do now in Portugal. My daughter is going to be an assistant US attorney in Baltimore. She’s now an attorney for Howard County which is where Columbia, Maryland is. She is the mother of my grandchildren, but she says to me, because I talk to her about them, coming to visit them, and, of course, you guys. She says, “Yeah, I know, they’re the main attraction.”

Interviewer: You’ve got good reason to be proud of your family and all they’ve accomplished. We’re coming to the conclusion of our interview here, but let me ask you this? Do you look back on your own life as a Jew? What do you take away from it? What’s your take away or what’s your broad feeling about your life as a Jew in Columbus, Ohio?

Goldmeier: I would not have traded growing up here. In my experiences, through Torah Academy, through Eastmoor, through the people that I met, I wouldn’t trade them for anything. There’s no place like Columbus, Ohio. I’ll just give you one last example before we go. My mom passed away in 2018 and it was February. I kind of have a bad back. I had back surgery. Rabbi Goldstein, she belonged still to Beth Jacob, was worried about her funeral, about having enough people to shovel, the first week of February how cold it would be. He didn’t know how it was going to turn out, how many people would turn out. Rabbi Goldstein called Neal Shapiro who is in charge of the Cemetery Committee at Agudas Achim. He called Neal and Neal is older than me, okay. He said, “Neal, maybe you or you could find someone to help out with this because we need to get enough people to help shovel.” Neal said, “Who passed away?” He said, “Helene Goldmeier.” He said, “David Goldmeier’s mother, I’ll be there, don’t worry.” No worries. I see Neal once or twice a year. We were friends from high school. My doctor is Marc Carroll. I need something. Marc is from high school. People I grew up with, and people say this about Columbus, doesn’t make a difference. It’s just two people I’m mentioning, a hundred, if you need something, you grew up here, this is the best place. It was a great place to raise my children. I definitely would not trade my childhood, my adulthood, all of it, Columbus, Ohio. We didn’t even talk about Ohio State football. It’s just the greatest place. I’m confident that when more people find out about it, as they have been in the last few months, in joining our community that they will make it go even higher and higher and better and better.

Interviewer: With that we will end our interview with David Goldmeier. I’m Bill Cohen for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society.

Transcribed by Rose Luttinger