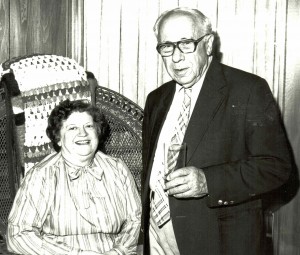

Harry Schwartz

Mr. Harry Schwartz and his wife Sara are being interviewed at their home at 967 S. Cassingham, Art Levy is the interviewer. Today is November 5, 1987. Okay, Mr. Schwartz, how far back does your memory go to Europe?

Schwartz: To Europe it goes back about to 1907 or ’08.

Interviewer: I didn’t mean to phrase it that way but it’s all right since you told me. What did your folks do in Europe?

Schwartz: My father’s family were tanners, manufacturers of leather.

Interviewer: That answers a question for me. Continue, and then I’ll get back to it.

Schwartz: And they were located in a small town under the Tsarist Russia in the gubernia or state known as Volhynia Gubernia. The capital of that state was Zhitomer. The city of Zhitomer may be familiar to a lot of people who came from Russia from that area. It’s in the Ukraine.

Interviewer: You told me where it was located near a bigger city, 40, 50, 60 miles.

Schwartz: Actually I just gave you the description of the province. The name of the gubernia or the state and the capital which is Zhitomer. Another city of a lesser area, like you would say a county of that gubernia, the district or whatever they call it. They don’t call it in Russian it was uezd, and it was Lutsk, a town named Lutsk. So to describe my father’s address in Russia if I was to write to him a letter, right now, back in the days when he was in Russia in the 1907 and all that, it would be addressed to Mishtetska, Sofiyevka, Lutsk Uezd, Volhynia Gubernia. So this little town was a village of Sofiyevka, the uezd, the larger area was Lutsk and the capital of Volhynia was Zhitomer.

Interviewer: Uh huh.

Schwartz: I gave you the address. You can write a letter.

Interviewer: When did you come to the States?

Schwartz: I came to this country, I came by way of Baltimore to Columbus in the spring of 1914.

Interviewer: Did you come by yourself or with your parents?

Schwartz: Came with the parents. My father lived in Columbus for about four or five years prior to that date. Before that he lived in Baltimore, Maryland. So my dad left Russia, Tsarist Russia, we’d say around 1906 or maybe ’07, probably 1906, immediately after or during the Russo-Japanese war.

Interviewer: It’s always interesting to me, I’ve heard stories from parents of my friends who’ve come over from Russia, why did he leave?

Schwartz: Contrary to many stories about Jews from Russia running away mostly because of the army, going to the army when they were in their early 20s, my father was, reported to the army when he was supposed to report. He was rejected. My dad had papers with him and I saw where he had a rejection primarily because he was the first-born of the family of eight children and they were in a rural area and under Tsarist rules, he was more or less exempt from military service and so he came about the time with a Russian passport. He did not run away from Tsarist Russia.

Interviewer: Why did he come to Baltimore and then why did he come to Columbus?

Schwartz: My dad came to the United States primarily, as many immigrants of that period, to leave the hardships of Tsarist Russia and I think the primary reasons were economic and it also was a time when a lot of young Jews left Russia at the time. It was the period when many of the Jews in the Ukraine during the pogroms and all that, although in my dad’s village, they never experienced any pogroms or any massacres or any sort of anti-Jewish, anti-Semitic actions against the Jewish community. He left Russia primarily I would say because of economic reasons. And he came to Baltimore, Maryland because of some relative of his family, a landsman was in Baltimore so he went to Baltimore, Maryland. He began, when he came to Baltimore, Maryland, his first job he told me was for a contractor, you know, digging basements and the first Friday when he was told that he would have to work on the Sabbath, he did not come back to work and there was a big cave-in. He always told me the story and he figured that had he gone to work that day he might have, his life then would have been endangered.

Interviewer: Sure.

Schwartz: So my dad tells me that instead of being in that kind of a labor job, he ended up in the garment business as a presser, pressing pants for a manufacturer and in a short time after he started, he became a kind of a sub-contractor. In other words who- ever the boss or the owner of the factory was would contract out to my dad a certain number of pants to press and my dad would take them to his place where he roomed, and he got a room in a basement with a pressing machine, and that’s with the old iron, you know, that were probably heated by coal or gas, and that’s when he started his business in the United States as a presser. And he stayed in Baltimore, Maryland and people he stayed with there, their name was Weisblott. I don’t know their relationship to us if any and he stayed with these Weisblotts for a few, maybe two or three years and he brought his brother, his third brother Sholem, who also came to America and came to Baltimore and stayed with my father. And the next place he went to was to Columbus.

Interviewer: Why?

Schwartz: Now, that’s the reason I introduced my Uncle Sholem. When my Uncle Sholem who came to Baltimore stayed with my father and went into the same business as pressers, he was married to a woman by the name, Yiddish name of Brocha, her name was Keller. My Uncle Sholem was married to this Brocha and this Brocha had a sister by the name of Chana and Chana was brought to the United States and straight to Columbus by Beryl Katz. Do you know the Katz boys from the tire business?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: Their father who lived in Columbus at that time, he went back to the Old Country to the same shtetl, you know the hometown of my parents, and he took Chana, my Uncle Mottel’s wife Brocha with him. She probably was only about 18 years old. He brought her to the States, he brought her straight to Columbus, and she was married here in Columbus and her so-called local Godfather was Boruch Finkel- stein. You know Dorothy Finkelstein who is now at Heritage House?

Interviewer: Yeah, I didn’t know she was at Heritage House.

Schwartz: I mean at Heritage Tower.

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah.

Schwartz: At Heritage Tower? Her father who used to live on Parsons Avenue, her father was a big scrap dealer here in town. His place of business was on South High Street and he more or less took her under his wing and she got married to Beryl Katz and they moved and lived in a little house on Fulton Street near Grant Avenue and Beryl and Chana Katz, their children now are Phillip Katz, they call him Occye Katz.

Interviewer: Occye, yeah, Betty.

Schwartz: And Norman Katz.

Interviewer: Betty Dworkin. They have a grandson that I’m not sure but I think his name is Barry. He’s a sports columnist.

Schwartz: Now he’s a sports announcer. So that’s how Beryl Katz’s Chana came to Columbus. So when my Uncle Sholem who came to Baltimore and stayed with my father in business and pressers, when he found out that his sister-in-law Chana Katz was now living in Columbus, he communicated with her and she told him or asked him to come to Columbus, that Columbus is a freye veter, is a very, very nice, clean, open city.

Interviewer: And a golden medina?

Schwartz: Golden medina was not the words supplied here.

Interviewer: Okay.

Schwartz: The idea was it was a kind of an open, rather than a large city sweatshop environ- ment. Over here it was free air, fresha luft.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: And that’s, she asked her brother-in-law Sholem to come to Columbus and within a year or so, Sholem wrote to my father in Baltimore and my father came to Columbus. So when Sholem came to Columbus, Katz was already a fruit peddler here, a settled member of the Columbus Jewish community, you know, who lived on Fulton Street which was at that time the center of the Jewish community in Columbus and my Uncle Sholem came here and since Beryl Katz was a fruit peddler, my Uncle Sholem became a fruit peddler, bought him a horse and wagon and started peddling. And within a matter of a year or two, my father came to Columbus for the same reason and he too became a fruit peddler. And after he started as a fruit peddler, he also bought a stand on North Market and on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, he stayed on North Market and Tuesday and Thursday he peddled.

Interviewer: In the coming generations when they hear this tape, they might not know what “peddling” means.

Schwartz: All right.

Interviewer: Tell them.

Schwartz: A huckster. A person who drove around with a horse and wagon with whatever he was doing, either if there were a lot of junk dealers in those days, junk peddlers they called them.

Interviewer: Uh huh.

Schwartz: And there were also a lot of fruit peddlers, they called them. And I recall later on when my father brought us here to Columbus, I went with him. And he had a route on Indianola Avenue. My father was a very, very shy person by nature, very reserved, very shy. He was also a very handsome man. And I remember sitting next to him on the seat with the horse and wagon on Indianola Avenue where he had some nice good old middle-class Protestant goyim as his customers. When my father started yelling “Strawberries” or whatever he was selling, he really looked around to see if anybody heard him. He wished they didn’t because he was so shy and bashful about it. But he, that was his business. He was a fruit peddler.

Interviewer: You mentioned “fruit peddler”. Do you remember Sam Smoler, Nat Smoler?

Schwartz: Yes.

Interviewer: Did you know their father? He had a, he was a fruit peddler. He had a wagon that was enclosed in glass windows.

Schwartz: All right. I’ll tell you about the glass windows. The early peddlers, the early people who were in that business, the horse and wagon, that’s what it was, they had an open wagon, large wagons, pretty good-sized wagons, sturdy because they had to load it up with a lot of fruits and vegetables and go out on a route in the city. A few years after we came here which means a few years after 1914, they began to build glass, they called “glass wagons,” which was actually like a little bus only it was horse-drawn. And they would have all of their, the bus inside was lined with shelves and glass windows and the peddler would stop at the customers and the customers would come out and there was a door at the back end of the wagon and he would sell them whatever. They would come into the wagon and see what they were buying and this was the glass wagon.

Interviewer: Uh huh. I never thought of it till just this second. I can picture Mr. Smoler’s wagon. It may have kept the fruits from freezing in the wintertime too because they were probably gone all day.

Schwartz: Well they didn’t have, you know, it could and it did probably but there was no real big problem with that because most of them carried a tarp, you know, to cover up the open wagons. Most of them were open, had open wagons because frankly they couldn’t afford to buy a glass wagon. It was expensive and most of the peddlers didn’t have it.

Interviewer: Well you know peddling from a wagon, in my time they would peddle from a open truck. There was the Goldberg boys on 18th Street and Meyer Goodman, the oldest Goodman boy. They’d go up and down the streets and yell “Strawberries, strawberries”. They’d sell them out of the crates.

Schwartz: Right, right. Well this is the way it was done and of course my father, as I said, bought this stand on North Market so he had part of the week he stayed on Market.

Interviewer: Uh huh. You said that your parents were tanners in the old country.

Schwartz: Right. Now I’ll tell you about tanners.

Interviewer: Okay.

Schwartz: My mother’s side, my mother’s people, my mother lived in a different town in the same general area in Volhynia Gubernia. My mother’s folks were also tanners and that’s how the shiddach was arranged by the two fathers, each one meeting somewhere when they met at some of the leather fairs. Where they had these big fairs in certain areas of Russia where they would take their finished product which was leather, to sell. They would meet at these fairs. And these Jews would get together and naturally, you know, you’d know Mr. So-and-so from such-and-such a place and that’s Hayim Ber from such-and-such. My grandfather’s name was Ber, Bill Ber they called him. And he and my father’s father met. ‘Course he had an eligible son. The other one had an eligible daughter and a shiddach was eventually worked out and my father married another tanner’s daughter. And now I have told you just, you know, how my father comes to Columbus.

Interviewer: Now there’s something that doesn’t fit in there. If my memory serves you right, you were in the hide business too, weren’t you?

Schwartz: Yeah.

Interviewer: With your brother, was he your brother . . . .

Schwartz: No.

Interviewer: the other Mr. Schwartz?

Schwartz: He was an uncle.

Interviewer: An uncle?

Schwartz: Here’s what it is. After my father and his brother Sholem came to Columbus and settled here and were in the fruit business, within a matter of maybe a year or two after my uncle Sholem came to Baltimore, Maryland to my father, my younger Uncle Joe . . . .

Interviewer: His name was Joe, that’s right.

Schwartz: Yeah. My Uncle Joe Schwartz came to Philadelphia to another member of the Schwartz family from the same village who was my grandfather’s brother or else my uncle or another way of putting it would be my Uncle Joe’s uncle. His name was Mayer Schwartz. He came to Philadelphia originally and my Uncle Joe came from the shtetl in Russia straight to Philadelphia and was in Philadelphia a year or two or maybe even more, and then when my Uncle Sholem and my dad had already established themselves as fruit peddlers in Columbus, they brought Uncle Joe over to Columbus and he too became a fruit peddler.

Interviewer: How did he get into the hide business? How did you get into the hide business?

Schwartz: The way my father got into the hide business, being a tanner from the Old Country, that was more or less his original first goal of trying to become a leather manu- facturer in this country. When he stayed on North Market inside of the Market was a meat market where the butchers were. So he went into the meat market and started talking to the butchers, what they do with the hides. And they told them that they sell them to a certain person in Columbus, a hide dealer. And he wanted to know what the hide dealers did with the hides. And they told him they sell the hides to tanners to make leather. So my father began to sort of pioneer in trying to get some information as to what people do with hides in the United States, where they get them and the whole bit of looking into the idea of maybe going in to become a tanner. He soon discovered that it would be impossible for him to go into tanning because of the lack of capital necessary to open a tannery in the United States. In the Old Country the family were tanners from way back in the last, to maybe 150 years before that in a very primitive style of tanning and in the United States they were already years advanced in the tanning process and the tanneries were located in certain specific areas primarily in New England and in Chicago. There were hardly any tanners locally. A few. One was in Zanesville, one in Sidney, Ohio, and they tell me there was one on Front Street in Columbus, Ohio, but very small, special tanners. But again my father soon realized he could not get in as a tanner but he also discovered that right there on Lazelle Street, right behind the Central Market on Fourth Street, right on Lazelle Street behind the Market House, were two hide dealers of the old German-Jewish people in this city. And my dad went to talk to them.

Interviewer: Who were they? Do you know?

Schwartz: I think one, I know one was Rosenthal and the other one was known as Meyers. I don’t remember him at all but Rosenthal, his name was Irvin Rosenthal. His father was in the hide business already which means that these two men of the German-Jewish community who probably came here in the 1840s, ’50s, were already established hide dealers and were already buying the hides from the Columbus butchers and from the surrounding. I later found out that every city, Cincinnati, Toledo, Dayton, Cleveland, had Jewish hide dealers. The biggest hide dealers in the Middle West and the biggest hide dealers in Columbus and in Ohio and they were big collectors of hides and Ohio was known in the trade as one of the best sources for a certain quality hides, good quality hides, primarily because of the feeding available to pasture as well as corn available to livestock. So Ohio was known in the trade, in the business of producing good livestock, therefore good hides, quality hides and many of them because every farmer in Ohio if you traveled in the olden days before the freeways, you could look at each side of the road and you would see farm houses and you would also see a few cows and horses and sheep and hogs all around. And there was a lot of them and the dealers were in, the major dealers were in the big cities and the smaller dealers, who were also Jewish, in the smaller towns. It was customary for a Jewish junk dealer located in a small town in the wintertime to buy a few hides because it was also customary in those days for the local, the native farmers, when the weather turned cold, would have to kill a couple of hogs for their winter supply of meat, of pork products and also one or two or maybe more cows or steers for their meat, their requirements for the winter. Plus in every little town in Ohio there was either one or maybe four or five small butchers who supplied the meat demand for the entire community and so there was a source of hides. And then when my father finally decided to get out of the fruit business and get into the hide business, he became what was known in the trade as a “country hide dealer”. Again, he got a horse and wagon and went to Reynoldsburg, went to Kirkersville, went to Hebron and to other little towns around here, around the city of Columbus as far as well maybe a radius of 50 miles or less, to buy hides and in the beginning, before he gave up the fruit business, he was already buying hides and he put the hides in the cellar of our house on Donaldson Street and my mother cried every day because the smell and the stink of the hides were in the basement because he had to bring them down there the raw hides, salt them and cure them in order to be able to preserve them so they won’t rot and later on sell them to a bigger hide dealer either in Cincinnati or Dayton or wherever, and my father first started salting hides on our street, in the basement of our house on Donaldson Street. And that’s how my father became a hide dealer and as time went on he gave up the fruit business altogether.

Interviewer: Uh huh. Very interesting. Now back in my memory I remember that you were in the hide business. Of course you say “they went out in the country”. You went with your dad because you say “cows all over”. I used to go with, my father was a junk man, picked up rags and steel and I used to go with him in the summertime. I can remember cows all over the place.

Schwartz: Well this was the sources that I described it to you. But what I, in my getting into the business, is a chapter and a story by itself because I have to go back to Russia with you and get me to the United States because my father was in this country before we came here, my mother and my brother Jack and my sister Sarah came here.

Interviewer: Well didn’t they in those days, didn’t they come over and work and save so they could bring the rest of the family over?

Schwartz: My father, here’s what happened in our case. You’re right on this usually doing. This is what happened in my case. My Uncle Sholem who lived here, you know, in Columbus with my dad, who was the brother-in-law of Chana Katz.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: He went back to the Old Country in 1913 or maybe even 1912, 1912 probably. He went back to the shtetl, to the home town. He brought with him as I understand it about three or four thousand dollars that he had saved back from the first day he came to America to Baltimore, Maryland until he then came to Columbus and until he went back, he saved up not much over $3,000 and maybe four. And that money he came and invested in the tannery in the old family tannery in the shtetl in Volhynia. Now my father in 1913 began to think of going back or bringing my mother here. My mother would not make the trip across the seas by herself so my father went back to Russia from Columbus. He sold his stand on North Market. He sold his horse and wagon and he had $3,000 saved up all these years. And he went back to the Old Country with the same goals as his brother Sholem, to invest it in a tannery and modernize it, start buying a little equipment and machinery, instead of using the old primitive process of tanning hides and I could tan you a hide the way my grandfather did ’cause I was all the time around him, around there growing up in the tannery. So my dad decided to go back with this goal. My father told me this story, what made him come back to the United States. When he came to the “voggal” which means the railroad station between two major cities in the area of our shtetl, the city of Lutsk as I referred to you before, it was also another city of Rovna.

Interviewer: Uh huh.

Schwartz: Between, a point between these two cities was a little town called Keevriz like K-E-E-V-R-I-Z or something like that. There was a stopping point for a railroad, Russian, you know, railroad at that time. And from that point he bolagola, the Hebrew word, the Jewish word bolagola means a drayman, a person who comes, a man who drives a horse and wagon. The bolagola, the man who drives a wagon. Did you see Tevya, the play?

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah.

Schwartz: Did you see Tevya who was out there with a . . . . That’s the bolagola, you hear?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: Now. My dad told me this story when he came to the Kiversta voggal, to that railroad station . . . . And he went into the lobby after getting off the train, expecting to find somebody from the little shtetl of Sofiyevka or known also in Yiddish as Trochenbrod.

Interviewer: Trochenbrod?

Schwartz: They say Trochenbrod, to hire somebody to take him home. At the same time, the people were there who were also looking for passengers to take them to the various little surrounding villages or derfer they called them. Shtetlach or derfer, derfer is the plural for . . . ., a non-Jewish community.

Interviewer: I see.

Schwartz: The shtetl is a Jewish community, okay? My dad tells me this story. He stood there in the station. A Jew came in from the outside with his whip, horse whip in his hand, with his boots and his big long coat and he’s looking for my father, you know, a passenger to take to Trochenbrod. And as he walked in he went, this man, past a Russian gendarme, a police officer, also known as gardevoy. That’s a Russian word for a police officer. And my father saw the police officer knock this Jew right down on the marble floor of the boxall.

Interviewer: Huh!

Schwartz: And my father told me when he saw this act, he made up his mind right there and then that he was not going to stay there. He was going to turn around and go back to the United States. And my father did go home around, it was around after the first of the year of 1914, around probably March or April because it was before Passover. And about May, right after Passover, April or May, my father got the family, my mother, my brother Jack and my sister Sarah and brought us straight by way of Baltimore, Maryland, and stopped in the old place where he first visited, where he first started with the Weisblotts and he bought us new American clothes because he was already an Amerikaner, he got us all dressed up. He took us right to Columbus and when we got off at the Union Station, we took a Fulton Street car to Chana Katz. And that’s, we were always friends with the Katzs. There’s a lot of . . . .

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: That’s why I took you back. Now I’ve got to tell you one more story about connection with, which happened in the Old Country before I came here, if you’re interested.

Interviewer: Sure I am.

Schwartz: All right. When my father was here in Columbus before he went back, my uncle, another brother of my father, who was a brother older than my Uncle Joe who lived here in Columbus, his name was Muttel or Mordecai. My Uncle Muttel was one of two young men in the whole village who left the village to go to Yeshiva in Lithuania.

Interviewer: Was that the picture you showed?

Schwartz: That’s the picture I just showed you of my uncle.

Interviewer: Where in Lithuania?

Schwartz: In the major city Kovno, it’s Slobodka Yeshiva, the famous, famous Yeshiva known as Slobodka. A lot of people use that word Slobodka as if it’s some kind of a mythical, funny, you know, fictional word. It was a town, a suburb of the main city. The capital city of Lithuania was Kovno and right across the river was a suburb, a totally Jewish community of, you know, which was known as Slobodka and in Slobodka right on the bank of the river was the famous, was a famous “Rabbitza Gahona” Yeshiva. And the Yeshiva was named “Rabbitza Gahona” only because where a famous rabbi of Lithuania was Rabbi. He was the rabbi of the city of, Chief Rabbi of the city of Kovno. And Rabbi’s yeshiva was, where my uncle Muttel left that little shtetl at Volhynia Gubernia, went all the way to Lithuania which is on the west coast of Russia, on the western part of Russia, and went to Slobodka Yeshiva, the first Jewish boy. Another boy in that same town left and he went to Vilna which was also in Lithuania toward Poland. ‘Cause that particular area shifted back and forth Poland to Lithuania to Russia and so forth. But this other young man, maybe I’ll think of his name. Anyway he went to Vilna. Vilna had a modern type of Yeshiva. They had secular as well as religious learning. He learned Russian and he also learned Jewish, you know.

Interviewer: Hebrew?

Schwartz: Hebrew. But primarily Russian and drifted into a completely, totally like a univer- sity education and was studying engineering. Whereas my uncle remained in Kovno at the Slobodka Yeshiva and he was already, when I was 13 years old my uncle Muttel was already a young man who had smicha to become a rabbi. But he continued to go back to study and every other year. It was later, a couple of years before we left Russia, he came in 1910, he came home to report to the service cause he became 21 years, he had to report to his military duty. And they gave him a deferment for another year and he came back the next year and they gave him another deferment. And when he was there the last time, I was a little boy ten years old and my father was in Columbus, Ohio. And my uncle came home on a visit. It was in the wintertime and he came home, you know, to report for duty, you know, to report for the military service. And jokingly to my mother, my uncle said in my mother’s presence, he said to me, “Herschel,” my Jewish name was Herschel, and he said to me in Yiddish, that’s the only language I spoke, “Herschele,” the diminutive of Harry . . . .

Interviewer: Yeah I know.

Schwartz: “Do you want to go with me to the Yeshiva?” And I said, “Yes”. I was, it was in the wintertime and I was standing against the oven, the heater and warming myself and he said to me, “Do you want to go to the Yeshiva with me?” and I said, “Yes,” and within a matter of a couple of weeks or so when he had to return, he was given another deferment, he took me to Slobodka Yeshiva with him. Now that trip is an interesting one. My mother, my uncle and I, for the first time I left the shtetl where kerosene lamp was the form of light in the house and candle light. My mother had a beautiful living room, the only living room with wooden floor. Maybe the second one in that shtetl and my mother took me and my uncle and hired this bolagola to go to the voggal where my father had this experience coming back home, for me to take a train to go to Kovno which was in Lithuania. We traveled from our village in the day. We left during daylight. When we got to the railroad station it was dark already. The train came. I never saw a electric light or a gas light, didn’t know what it as all about. Never saw a train in all my life. Never heard a whistle of a train in all my life. I was already ten years old and I recall on the way to the voggal from the shtetl as we were driving on this road, a sandy road, and the only time it was sandy was when it was summer or frozen. Frozen when it was the wintertime, it would be a sled. But it happened to be still in horse and wagon. I heard what was a railroad whistle, horn, and I asked, “What was that?” And I remember my uncle kidding me, but I didn’t know that he was kidding; he’d say it was a cow in the forest. And within a short time I was at that railroad station and I saw the train and my uncle and I got on the train and he took me into the railroad car and he got me a seat and I sat down near a window looking out. In the meantime, my uncle left me sitting there by myself, first time on a train, and he went out where the entrance, door of the car, the railroad car, where they were coupled together and he was talking to my mother. You know, she was standing on the platform.

Interviewer: Crying.

Schwartz: I didn’t see my mother at that point. When I looked around I suddenly heard the train, we were getting ready, steaming up and making a noise and jarring. The railroad car, I thought the train was leaving with me and without my uncle and I, my heart just fell right into my stomach. My nose was squeezing the window of the train and pretty soon my uncle came in and he saw me and the train then slowly got started. I saw my mother and I kept looking and looking and pressing my nose and that was the last time I saw my mother for two and a half years. And went straight to Slobodka. The first, next station was the city Kovi, the, Bob Mellman’s wife Ruth, she comes from that town. The Volk family comes from that town.

Interviewer: Yeah and one was married to your uncle.

Schwartz: That’s right. They come from Kovi they call it. Don’t confuse it with Kovno where I was going to in Lithuania.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: The next day we finally came, the next day at night we came to a city called Bialystok which was a large city. You were already approaching the Belorussia, White Russia. We were getting closer, northwestward, northwestward. And finally we began to hit cities like Grodno and finally on the third day at night, and I’m talking about from the time we started horse and wagon at home, in the village, in the shtetl, we arrived at Slobodka and my uncle of course was at home in Slobodka. That’s where he had already stayed four years studying. That night he went to a place where he was to room. And he, you know, took in our baggage and everything else and got settled and he took me for the first, that evening he took me with him to the Yeshiva, the first time I saw that big hall, like a big synagogue with shtenders. You know what a shtender is? (Editor’s note: a lectern)

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: Know, with benches and the students, all the students, probably the youngest would be 18 years old, standing there with a candle as the light on the shtender and with the Gemorrah, a large tractate of the Talmud on the shtender. A lot of them were rocking back and forth and studying just like nobody’s around them. They just were in oblivion. They were themselves in the book.

Interviewer: Sure.

Schwartz: And they were singing in singsong, in a chant on the Talmudic, I could sing you that, that missach. And then you could also see here and there two of them arguing and discussing a principle or a point of law, a point of the Talmud. And this was going on all over the Yeshiva. And large lamps with crystal chandeliers holding with lights, with candles was the light and they had to have an extra candle right on the shtender if they were not underneath one of these chandeliers, to give sufficient light to read. And this was the mode of study and there was a mashgiach, like a superintendent, a supervisor who was there and every now and then, later on I found out if they had some difficult subject or some difficult passage in the Gemorrah, they could go over to him and discuss it with him. Or he would send them to a senior, another senior student there. I was introduced into that Yeshiva which was known as the “Rabbitza Gahona” Yeshiva. I was a ten-year-old little kid and I was too young to go to that Yeshiva because it was all for adults.

Interviewer: Uh huh.

Schwartz: And so my Uncle Muttel arranged with the superintendent or the Rosh Yeshiva, the mashgiach and all the rest of the officialdom, whatever their names were, he arranged that he would be my tutor and I would just be there and he would go to the Yeshiva and he would be my teacher and I would just do my lessons that way, instead of sending me over to Kovno to the big city where they had a Yeshiva for youngsters my age. He didn’t want me to go across the river to the city of Kovno to go to that other little school and this is how I was introduced to the Yeshiva for two years with my Uncle Muttel. And when I came back from the Yeshiva two, this third year after being in Kovno, is when my father, a few months after that my father came and right after Passover, I was already Bar Mitzvahed. When I came back to, I came back and became Bar Mitzvahed in the shtetl before my father came back to Trochenbrod, to the village. And that’s when I was Bar Mitzvah and my mother did take me, during that winter, she did take me to a Yeshiva for young boys in Rovna, R-O-V-N-A. But I only stayed there a few months because my father came home and that’s when he was ready for us to go back to the United States. I mean my father was ready to go back and we went. He bought the steamship tickets from an agent and everything was arranged and we took a train and at Hamburg, Germany, on a steamship known as the Prima, a German boat. And from there we went right straight to Baltimore, Maryland and I came from Baltimore, Maryland where my father took us to a department store and got us all dressed up in American clothes and I became, and I came off over here at the Union Station. The year when I came back from the Yeshiva, my mother got me a Polish, a teacher who taught me Polish. He used to come into the house. I didn’t go to Cheder because I was already came home from the Yeshiva and we were preparing going to America. She got this Polish tutor to come into the house to teach me Polish because the Polish alphabet is Latin alphabet, the same as the English, whereas the Russian, I also had a Russian teacher begin to teach me Russian. So I was already reading Russian and also tried to teach me to read Polish and when I got off the Union Station over here, the first American word, English word that I read was Fulton, F-U-L-T-O-N, and I spelled out Fulton and that was the street car we took to come to the Katz’s on Fulton Street. This is how I got . . . .

Interviewer: At the Yeshiva?

Schwartz: Right. When it was decided that my uncle was going to keep me in this “Rabbitza Gahona’s” Yeshiva and I was just, and he was going to be my tutor there, it was customary in the Yeshivas of that period, the way the students were supported, you may have heard the words essen tag, eating days. That simply means that students were assigned different days for different families. And since my uncle had already been there, he already had a certain number of homes that he was regularly assigned to eat. I was assigned also to go for the first time away from home to a home for a day and so . . . .

Interviewer: Were you assigned to the same homes that he was?

Schwartz: No, no. That would be too much of a burden for one family, one student. Any- way, I was assigned among for different days to different families and most of the families that I had to go out to were in Kovno, not in Slobodka. So when I learned a little bit how to get around, all I had to do was go across a bridge, the river. By the way the city of Kovno was actually where two rivers joined. It was a river called Vilya and another river called the Nieman. The Nieman is a familiar word. So the Vilya and the Nieman converged around Korno so on one side of the city of Kovno is the Nieman, a large river which goes into, I believe, into the Vistula and goes into Germany someplace and that’s a big river with a lot of transportation of commerce to Germany. The Vilya was a small river and I had to go across that small river to eat on certain assigned days, to eat dinner, just late afternoon meal. In the morning there was no problem. A woman would come by every morning to where we roomed and she would come by, have a large basket of rolls. Frankly I never ate any bagels. I didn’t know what bagels were. But they had large rolls and then another person would come by with two big milk cans on a mule plank carrying them and we’d measure out milk. So we had that but for the main meal, we had to go out. Unless you were able, you know, to self, you know, to have financial support yourself. And I’m sure there was quite a few students who could take care of themselves, whose families could support them. The first few Saturdays when we arrived, when I arrived as a new student, I was sent to a little community in Kovno on a hill known as the grinner bard, the green hill. As a youngster already 10 or 11 years old with a few weeks in a big city, I was already beginning to find, you know, my way around. By the way in recent years I found out that Seiferas who is, you know, is related to Godofsky . . . .

Interviewer: Ben Seiferas?

Schwartz: Ben Seiferas comes from that town. When he heard me once mention that I was in Slobodka, that’s when we found out that he came from Slobodka, that he came from Kovno. So I was assigned to a home on the grinnen bard in the city of Kovno for Shabbos, for the Sabbath. Which meant that I would have to stay overnight because I would, you know, have to go across at night, to go home. I mean go back to my rooming house in Slobodka. I had to stay overnight and I assumed that I was going to stay at this baker’s house, at this person that I was going to eat Friday and Saturday. And then Saturday; night I would go back to Kovno, to Slobodka. I came in. I was told to come to a little shul on the grinner bard and there my balibuss, the man who was going to be my host, was going to pick me up and take me to his home for the Sabbath meals, Friday night and Saturday. So I went to the little shul. It was no bigger than the Ahavas Sholom shul used to be over here on Washington Avenue near Donaldson, next to the Big Shul. And a little shul like that, picture that. And I came there and all I remember is right after the service this man with a white beard comes over and like I thought he was whispering to me. But in later, I found out and after my uncle explained to me that this man had a throat in which he had a, the larynx was . . . .

Interviewer: Removed?

Schwartz: removed. And he had a kind of a whistle. And he always kept his hand when he was talking under his beard and you could hear him. Otherwise you couldn’t hear what he was saying.

Interviewer: I had no idea that they did that type of operation . . . .

Schwartz: Oh really?

Interviewer: that far back.

Schwartz: I want you to know that’s about 1912. So I came in, this man picks me up, he takes me to his home after the service and we had dinner and for the first time on a Friday night I’m eating pumpernickel bread after they made a motze over challah. Now in my little town where I came from and the kind of mishpocha that we came from, we wouldn’t be caught dead eating pumpernickel on a Friday night. And I ate my meal and everything else and figuring that I was going to have to sleep overnight. The man tells me that I have to go to the little shul to stay overnight in the little synagogue. I’m a ten-year-old kid. And he sent me to that little shul. So I went. I came in, nobody in the shul. I’m sitting there all alone. The only lights in the shul were the candlelights. And sooner or later they’re going to go out. And I’m beginning to be afraid. Away three days journey from home practically, first time away from my mother, I was my mother’s oldest, you know, favorite little boy, and here I am alone and since I made my own choice to go to the Yeshiva with my uncle, I was very, very brave to stick it out. So I’m sitting there and the first thing you know I began to think of all sorts of things that’s going to happen to me. And we used to have an old Mima Raisie, Tante Raisie who was known as the village storyteller for little children. And I remember scenes where a group of us would stand around her. She would knit, or in the wintertime she would be picking feathers for the feather beds or she would be shelling beans or peas or what have you because we were an agricultural village, a shtetl. This woman was telling us all kinds of stories, beautiful stories for children. She had all kinds. She also had some stories, scary stories. The story that my age in my shtetl, the super- stitious environment, one of the stories that I knew already as a child was that if you are in a synagogue by yourself, which was probably pretty common in those days for people, you know, roaming around, I was sitting in that shul all alone and the story comes to me that if you are ever caught where you would have to live, have to spend time in a synagogue, the story is that midnight, 12:00, the shaddim come in . . . .

Interviewer: Was it . . . .

Schwartz: The “Halits”.

Interviewer: Halits, okay.

Schwartz: Now I used the wrong word. I said shaddim, that’s wrong. The “masson” come, the souls of the dead come to pray at 12:00 midnight sharp. They’re on time. And the story goes also that if, this particular story, goes that if you hear your name being called to the Torah at midnight, the rule is go up there even though you don’t see anything but you heard your name called you better. If not, you ain’t coming back. You go up to the . . . .

Interviewer: Bima?

Schwartz: bima, make the brocha as if you were in the shul and nothing is going to happen to you. I was sitting there.

Interviewer: Did you hear your name?

Schwartz: And I began to look to the candlelight going, you know, ready, just flickering, and I noticed a shadow moving on the wall by the Aron Hakodosh and I don’t know what it is and of course that story came to me that the “masson” were beginning to come in for the midnight service. You can imagine how scared I got at that moment. But I also knew the remedy to survive and I was getting ready to rehearse in my own mind the brocha for the Torah. Of course, pretty soon another person comes in, the beggars were always coming in to shul to warm up.

Interviewer: You were saying you told it to Sam Melton?

Schwartz: This same story that I just got through telling you what happened to me in that little synagogue. Years later when I was in the United States, already a practicing attorney, an active Zionist and we were going to New York, I was going to New York to some sort of a convention, and we got a cab and it happened to be Herman Katz and Sam Melton and I were in a cab. How the subject came up I don’t know but I start telling them this story that happened to me when I was in Slobodka Yeshiva and I kept telling that story. By the time I got through with the story we were already at the Taft Hotel. That used to be my favorite hotel in New York City in those days, the Taft Hotel. When the cab driver came out and opened the door for me to go out, he said to me, “That was the most interesting story. You ought to send it to the Reader’s Digest.”

Interviewer: (Laughs) You were saying that you saw the shadows and the beggars and whatnot were starting to . . . .

Schwartz: They started coming in. That of course relieved all my fears. Later on I surmised that what was happening was a fly was crawling around close to the candle. The reflection on the wall of the fly was like a big airplane coming down, you know, one of those big, big shadows looming.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: That’s what scared me and of course I already began to think in terms of the stories that I heard when I was a child and I’m still a child even then. And that, so they came in of course and I laid down on the hard bench, fell asleep, got up in the morning and the next day I spent the day for the next Shabbos meal after the service and before the evening, before the Saturday after the Havdalah, I took a street car to Slobodka to my rooming house.

Interviewer: You skipped one part. Did you ever get the aliyah? Did they ever call your name to come up?

Schwartz: No but you see, this was, I thought about it, see. This was the thoughts that came to me and all these superstitious stories that go around scare, the ones that would tend to scare little children. They’ve built into these stories a saving clause of some sort. They did not want any sad endings.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: Even I knew, living in these small villages surrounded by forests. In the village that we lived in, in my home town where I was born, we were surrounded by forests within just a matter of maybe like from here to James Road. You were in solid forest all the way around if you put a radius of that around the shtetl, you were in forest. And by the way our forest around there was the Radziwill Forest. In case you remember the Kennedy family.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: They, her, she came from the . . . .

Interviewer: Radziwill?

Schwartz: The Radziwill, or related to the Radziwill. So what happened in the, I just lost the train of thought here.

Interviewer: You were talking about the forest being so close, from here to James Road.

Schwartz: Yeah . . . . I want to tell you one more little story that they used to tell. They would tell stories that children got lost in the forest, children got lost.

Interviewer: Actually I’m sure they did.

Schwartz: And I’m saying that actually things happened and they used to say that they found the children maybe a day or two later and the children already would not be, you know, frightened to a point where they would go off their minds. The children had

heard stories that if you’d ask the children what happened, “Well my grandmother came to me.” It was strictly a . . . .

Interviewer: A bubbe meitza.

Schwartz: a mystical story.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: She thought her grandmother came. She lived within the life and within the stories that were told. If you would ask her, you know, what happened to her, “Well grandma brought me this and Grandma did this for me.” You see what I mean?

Interviewer: Yeah, so they survived.

Schwartz: You see?

Interviewer: They survived.

Schwartz: So they survived and it leads me to believe, you see, that all these old stories like that, if they were sad stories that story tellers, if they were for children, managed to have . . . .

Interviewer: Built it an escape clause.

Schwartz: Yeah, absolutely. So I already, see, was saved, you know.

Interviewer: Sure

Schwartz: Psychologically I was sound, you know. I didn’t have any problems.

Interviewer: But you wonder what kind of a person would turn a ten-year-old boy out to go to the shul and sleep by himself.

Schwartz: All right, I’m going to give you a comment on that. There were a lot of persons like that and there were a lot of, they have stories you know where, stories about the melamden, the teachers.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: The rebbes. And what I often hear, a lot of Jews and I can give you names but I won’t who would say the reason he cooled off and threw his tallis away and quit being, you know, a good Jew, so to speak in terms of praying and, you know, and obeying the mitzvahs and what have you, is because, ” I had a rebbe,” you know, “who used to beat me up or he would pull my ear or,” you know, and all this. And therefore they went away, you understand . . . . Now you had rebbes like that. But you also had wonderful rebbes who loved their children. I happened to have a rebbe who was, I never had a bad rebbe and I had a half a dozen of them in the course of my Jewish education in the shtetl, you know. And I never had those experiences. But I also knew that when I did experience some obnoxious person, a Jew, who mistreated a youngster in the same class, if I had that experience personally, it would not cause me to overthrow my Judaism, you know. Somehow I was fortified in my own convictions to an extent to know not to blame Judaism on a momser of a person.

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah.

Schwartz: You know? So what that particular Jew did, you know, did not hurt me at all, you know. In my attitude as a youngster, it did not affect my commitment to being Jewish in any way whatsoever. Somehow of course, later on when you grew up, and you learn and you read and you accustom yourself to understanding these things, it doesn’t, you can rationalize and understand, you know.

Interviewer: Sure.

Schwartz: So it didn’t disturb me one bit. Now why I came back from the Yeshiva. Before my father came back, I had already came back to my shtetl. I wasn’t feeling well and my uncle was, you know, took me to a doctor in Kovno and the doctor examined me and he told my uncle that there was nothing physically wrong with me and “baked ahaim,” well this was his Yiddish expression, “I’m homesick”. So it took two years of being away from home and as much as I assimilated, you might say, into this new environment, it must have had some sort of effect on me of being homesick and that’s what happened. Now, so when I was in Kovno I considered that my two years and a half of experience in Kovno had the major effect in my life both as an individual and as a Jew and I think it actually directed me from then on because, number one, I was exposed to a big city from the shtetl. I saw a street car, I saw electric lights, I saw big boulevards, I saw a tremendous lot of people, all sorts of people. I was already traveling on a railroad and I want you to know that when I was probably 1912, I saw a movie in a park in Kovno. Running around, you know, between seeing, between a lot of Russian officers, you know, standing around you know, the elite, you know, the intelligentsia were out, going, you know, strolling and strolling and here I was already going around because where I roomed there was a youngster about my age. He was a native of Slobodka so he and I were friends and we would just take off and go to Kovno across the bridge and we would be looking in the windows and going out to the parks and have a good time, you know, in this way. So I got to see movies, number one, and I got to see a circus.

Interviewer: You never think of circuses in Russia although I’m sure they had them.

Schwartz: Well they had big circus in Russia. In Moscow they had the famous, the Russian Czar, they had the terrific circus. We saw them not too long ago. But when we were in Russia, I’ve been in Russia twice with Sarah. We saw them, the big circus in Moscow. But I’m telling you, here I was a youngster already. In the shtetl life I probably would never have seen it until years later I would come to America and maybe not even see it for years and years if the circus came to Columbus. I got to see it when I was only 10-12 years old in backwards Russia you might say. Because I was already in a big city. Not only that, seeing a movie and not only that, in the flatland where these two rivers converged, the Nieman and the Vilya was a great big area of a flat, you know, land which in the winter and the early spring was floods, you know, come on. And the land is, they had it fenced in one time and you know what was happening down there? One of the famous Russian flyers was, came there to test, you know, for an exhibition, to fly. They built a wooden fence all around the area so only the military and the very high people, you know, high class people, were there. We kids, again, I’m going back to this youngster. We were out there trying to find a hole to be able to see. The only thing we finally got to see, when the plane took off. The chances are that fellow over there, that Russian guy, flew the same kind of a plane that Eddie Rickenbacker from Columbus after World War I started, flew the same kind of a plane. And the Czar, the Czar, had the same sort of planes testing them at that time. So they weren’t too far behind, so to speak in that area. So I got to see that when I was a youngster. But these Yeshiva bochers in the big Slobodka Yeshiva were not allowed to read a Yiddish paper. Yiddish, not allowed. Not allowed, certainly not allowed to read a Russian paper. But they used to get together in my uncle’s room, where we roomed, and they would send me to the bibliotech, which is the library in Kovno and in the city, to bring them a Yiddish paper, a Hebrew paper, books from the library and a Russian paper. One or two of these bokherim, or boys, you know, students, were able to read Russian. So they would sit around and they would discuss secular subjects, cheating, you understand?

Interviewer: Sure.

Schwartz: They weren’t allowed to do that. They certainly couldn’t bring it into the Yeshiva. They were already beginning to become exposed to the influence of the Haskalah. The period of enlightenment was beginning to penetrate even into the Yeshiva and these young students who were studying to become rabbonim, to become scholars in the Torah only in the Talmud, were already beginning to drift into the outside, in other words the . . . .

Interviewer: Outside world?

Schwartz: outside world was beginning to have its influence on them in here. And as little, as young as I was, I was exposed to that little environment. That’s what I’m trying to tell you. That that had a terrific psychological effect that actually guided me and influenced me for the rest of my life as a Jew. And these young people were already studying like that. When I walked out on the street of Kovno where I could buy Hatzfira which was a Hebrew newspaper, I could buy the Haynt Citalics which was a Yiddish paper, I could buy the Franck which was a Yiddish paper. I was exposed to that. If I would have lived in the shtetl I would never have known that.

Interviewer: That’s right.

Schwartz: If I would come to Columbus, I would know less. So I already begin to know what was going on in the world and the Jewish world. I was also exposed to the idea, to this concept of anti-Semitism. In my shtetl we had no problem with goyim. If a goy came in there, he was afraid. He only came in on weekends to buy his stuff, to buy his schnaps and to buy his provisions, whatever he needed, you know, for this, for his maintenance, for his . . . .

Interviewer: For his living.

Schwartz: for his living. So my experience in, away from home is actually what made me. Now, one more thing. When my dad was here in Columbus and I was in Kovno, he found out that I was in the Yeshiva. He started mailing me ten dollars every month from Columbus.

Interviewer: In those days ten dollars was a lot of money.

Schwartz: I’ll tell you what it was. I used to take the ten dollars and go to a bank in Kovno. The chances are that in the little village, in the shtetl that I was born in, they didn’t know what a bank meant.

Interviewer: Let alone a ten dollar bill.

Schwartz: Well they were . . . . The women of the immigrants who lived in America, they already knew what it was. But I’m talking about the general population. So here I was getting ten dollars a month from my father. I used to go to the bank and I would get nineteen and a half rubles. I therefore became the richest kid in the Yeshiva. I therefore did not have to go and eat cake outside. And as a matter of fact, my uncle and I lived off of that, you know in our rooming, in the room. But I did eat. Friday night and Saturday, ate with the owner of the rooming house who was a butcher and he had three sons. One was my age and the other one was much older and the, a couple of daughters. And I really began to see, you know, the life of a Jewish family in a larger shtetl, in a total large city environment where the oldest son was a bookkeeper who had a job in the city of Kovno. He was always well dressed and looked good. He was looked up to all the time because he was already of the intelligencia, of the educated. He had another brother. The other son was a worker in the butcher shop, in the slaughter house. The youngster was just growing up and the second, the third son, who was just like a teenager. Well Friday night, the biggest battle on Friday night at the home was he was trying to sneak out carrying a cane to go to Kovno, spatzerim up and down the boulevard. And you were not allowed to carry on the Shabbos, on the Sabbath. So I was beginning to get introduced to the way of the Jewish person getting exposed to the secular environment, to a non-Jewish environment. And since I told you my uncle discovered by taking me to the doctor that I wasn’t feeling well and all I needed was I was homesick, we left that year when my uncle went back and became, you know, for his reporting again to the service, I stayed home. My father came within a few months after that and in a few months after that Pesach of 1914, I came to Columbus.

Interviewer: Okay let’s . . . .

Schwartz: That’s it. (Blank space on tape) Well I’ll tell you, you might as well start with some sort of a question as to what you want to talk about in Columbus.

Interviewer: You arrived in Columbus when?

Schwartz: I arrived in the spring, the early summer months of 1914 and as I told you before, we came straight from the Union Station to Fulton Street to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Katz, the parents of the Katz boys who now have Katz Tire Company on East Main Street. As a matter of fact, their parents, Beryl Katz, his Jewish name was Beryl, he had a tire store on East Main Street and he and a brother of his by the name of David, who would be the uncle of the present Katz boys, were in partnership on Main Street in the tire business. And later on in the 20s when I became an attorney, I wound up representing the two Katz brothers in the dissolu-tion of the partnership . . . . We arrived I think it was on the Fulton Street car. Later on I guess Mr. Katz and my dad probably went to Union Station and picked up the baggage and everything else and brought it in and we . . . .

Interviewer: On the street car?

Schwartz: brought it in, the baggage probably with Mr. Ben Katz’ horse and wagon.

Interviewer: Oh.

Schwartz: And we moved in upstairs in the attic-like. It was like a, one of those little one-floor-plans like most of the little houses, brick houses in German Village now.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: And there are a few of them on Fulton Street now.

Interviewer: Where on Fulton?

Schwartz: Fulton Street near Grant Avenue.

Interviewer: Near Grant?

Schwartz: Yeah. The first alley east of Grant, just about there was where they lived. And the back of their house was Starring Street. And Starring Street ran from Washington Avenue west to Grant Avenue and probably farther west but I don’t recall, you know, whether it continued east.

Interviewer: Yeah there was a lot of Jews who lived on Starring, Fulton and Donaldson.

Schwartz: Right. So I’m going to proceed, you know from that point. When we arrived, we stayed upstairs in the Katz home until we found a house for us to move in. And we found a house on Starring Street which was in back of the Katz home, a little bit eastward. In other words our home now became, was on Starring Street, between Washington Avenue and Grant Avenue and we were, you might say, within the heart of the Jewish community of that time, the East European Jewish community of that time where we moved in because the whole street, little street of, actually we called it an alley. The whole alley between Fulton Street and Donaldson Street, on both sides of the street, all the houses that were there were Jewish homes with the exception of a couple of vacant lots which were scrap, what you called junk dealers at that time. And so on the side north of Starring Street was Fulton Street. That street was mostly Jewish. And on Fulton Street, on the north side of Fulton Street was the old Fulton Street School.

Interviewer: I went to school there.

Schwartz: Most of the students in Fulton Street School at that particular time were probably Jewish. Now this was in the early summer, you know, when we moved in there at that particular time. So we lived through the summer Americanizing, getting acquainted with the community. My father already knew the community because he had lived in Columbus before that for about three or four years or maybe two or three. No three or four years. And of course within a matter of a block, or less than that, corner of Washington and Donaldson Street was the old Agudas Achim shul which is now the Big Shul, and it was then the Big Shul and it’s now located at Roosevelt and Broad. And on Donaldson Street between Grant Avenue and Washington was the Beth Jacob. So walking out of our house on Starring Street we were just about a half a block to the Agudas Achim, about a half a block we would come into the back end of the Beth Jacob and right next to the Agudas Achim with just one vacant lot separating, was, or maybe two, was the Ahavas Sholom. The house that was next to the Ahavas Sholom belonged to Mr. Friedman, the father of B. B. Friedman . . . .

Interviewer: Oh yeah?

Schwartz: and Jake Friedman. And as a matter of fact, in just recent years, maybe a couple of years ago, I visited B. B. Friedman, he just passed away last year, and B. B. Friedman told me that the vacant lot located immediately adjacent to the Agudas Achim at Washington and Donaldson, which was a vacant lot next, on one side was a shul and on the north side of that lot was the B. B. Friedman home and that lot, B. B. Friedman told me, belonged to his dad and his father gave it to the Agudas Achim shul, he gave it as a gift to the shul.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: And that’s where they used to have the lawn things.

Interviewer: I remember.

Schwartz: Every summer.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: There was a big lawn fete on that lot and everybody came out you know, and all that. So this was the center of the Jewish life, you might say because Washington Avenue and Donaldson Street, Washington Avenue from Livingston even as far south as Beck Street, was Jews on both sides of the street. Donaldson Street from Parsons Avenue all the way to Grant Avenue was Jews. Livingston Avenue was a mix of Germans, old German-Gentiles and the Jews. Rich Street, Fulton Street east and west from about 22nd Street to Grant Avenue was Jewish practically 100%. Then we went into the alleys between because the next main street was Mound.

Interviewer: I lived on the alley in between Engler . . . .

Schwartz: So Engler Alley was also all Jewish.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Schwartz: Mound Street east and west was all Jewish. Then we go into Main Street, partly Jewish because it was business, no residence. But in the alley next, going north between Main and Rich, were a lot of Jews also all the way to Rich Street. And then when we get into Town Street we already begin to run into the old German-Jewish community of residents and there, and they extended, their residence extended all the way up east on Town Street to what became Bryden Road. So that was the area in which the Jewish community lived. There are some Jewish families on 22nd Street, Jewish families toward Livingston Avenue toward Ohio, Jewish families all the way up to Wilson Avenue and Oakwood Avenue. Just a few, just a few. People who could afford to, who had already established in the community for some time, I’d give you just a few names like the Goldbergs, the Danzigers, a few names, like that, the leading ballabitim of the Agudas Achim. You get to move eastward as far back as, and I understand that the Wasserstroms lived on Ohio Avenue.

Interviewer: Ohio, 799.

Schwartz: So you see the general community of some of the people who had became a little bit better off in the 20s began to move eastward and most of the kids who went to Fulton Street School for their education, a good percentage of them went to Central High which was located in the more or less, Broad Street. It’s before that, it was on, I think on, somewhere on State Street, Central High. Later on it was on Broad Street. (Mixed voices) East High.

Interviewer: Commerce? Wasn’t it Commerce?

Schwartz: It was called Commerce High.

Interviewer: Before they made it . . . .

Schwartz: And later on it became Central.

Interviewer: That’s right.

Schwartz: Commerce is the one where they would start teaching some subjects like typing and shorthand and what have you so a lot of the youngsters who did not want to go to, who didn’t expect to go to college, and most of them did not, would go to Commerce to learn shorthand and typing so they’d get jobs, you know. Most of them though went to South High, the old South High which was on Deshler near Whittier, right near Deshler Park. And Deshler Avenue near Whittier.

Interviewer: Yeah. North of Whittier.

Schwartz: Yeah. And Deshler used to be the name of the street, you know. And Whittier was known as Schiller Park, Schiller.

Interviewer: Was it, I don’t know?

Schwartz: Yeah it was known as Schiller and later on, during World War I, they started changing the old German names to American so they named it “Whittier”. But most of the young people of my generation here, my contemporaries of that particular period, went to Fulton Street School and then to South High School. When I came here, as I said before, in May, the summer I spent already getting acquainted with the kids around the neighborhood, began to pick up a few English words and then of course, Mrs. Katz took us, the family, took me, my sister Sarah, and my brother Jack to Fulton Street School, registered us at the first grade and I graduated from Fulton Street School and went to South. Then I graduated from South High school and went to Ohio State University.

Interviewer: What year did you get your law degree?

Schwartz: In 1925. I’ll give you a little bit of a story about my background in the Fulton Street School. I get a lot of comments from a lot of people who talk to me and they don’t sense a sort of a Jewish accent because after all, I came here when I was 13 years old. And most of my contemporaries who came here about the same time and at my age spoke with a definite Jewish accent. And I have to thank Miss Scott, the Principal of Fulton Street School, for actually teaching me English so that I picked up the pronunciation in such a way that I have to be thankful to her to be able to speak without a noticeable accent. Now Miss Scott I understand had a sister who also was a teacher at South High School. They were two teachers. Now Miss Scott at Fulton Street School was the Principal.

Interviewer: She was Principal when I was there.

Schwartz: That’s right. Now, and Sarah, you know, my wife Sarah, she went to Fulton Street School. Most of the Jewish kids went to Fulton Street School. Now, what happened to me is they put me in the first grade when I came here and I was already a 13-year-old boy. I was in my fourteenth year. And I, the little desks were too small for me so they gave me a bridge table and a chair in class for me to sit on. And within a matter of a few weeks, maybe three or four weeks after I was in that grade, I remember Miss Howell, a school teacher and a lot of people of that generation remember Miss Howell when they were kids, you know, they were maybe six years old when I was already a 14-, 15-year-old, Miss Howell called in Miss Scott the Principal and she went over. The Principal, Miss Scott came over into the doorway into the first grade room. Miss Scott asked me to go to the blackboard and she must have sensed that I, you know, must have some sort of a background, some sort of an education above the first grade. And my education above the first grade was actually not in English but I did have a certain amount of Jewish education, a little bit of Russian, just a beginner’s Russian, beginner Polish, in order to familiarize me with the reading of English. And my only secular, other than the prayer book and the Chomish and going to Cheder so my only secular education at that particular time, was in Yiddish. So she sent me over to the black- board, Miss Howell. And she put down a column of figures, put a plus sign in front of it and I knew that was for me to add it up. That plus sign was the only thing I understood and of course, mathematics, the figures, I knew what it was about and I drew a line and I added it up in Yiddish in my own mind and I put down the correct total and she was all excited. Miss Scott was all excited, you know, that I was able to add. Then she put another two lines of figures with a minus sign in front of it and again in Yiddish, I subtracted it. Then they realized that I was already good at addition and subtraction and they immediately considered, as a matter of fact, she put a multiplication sign and I did that too. So this is all that I had brought with me from the Old Country in my Jewish education. And she brought in Miss Scott and they noticed that so I skipped, within a matter of a week or so, they put me in the fifth grade.

Interviewer: From the first?

Schwartz: From the first to the fifth and to this day I don’t know how to spell. I’m bad at spelling because I really never learned to spell real well. But I was learning my English most of the time just from talking but during the time, during that particular time also, Miss Scott used to take me into her office for at least an hour every day practically. She’d call in Miss Becker who was a German teacher and in those days they taught German in public school in the lower grades. It’s only during the time of the war that they stopped. I’m talking about the first World War that they stopped teaching German in the lower grades. And Miss Becker’s German and my Yiddish and Miss Scott testing me for English by saying to me I should go over to the board, you know, and push a button number two and if I didn’t know what she was talking about, Miss Becker would tell it to me in German. And I really did not know German but my Yiddish was good enough to understand. And also she also taught me, “Go bring me a glass of water”, and Miss Becker would also translate it to me for pronunciation. And if I pronounced the word “water”, the “w” with my Yiddish or Russian influence, I would say “vader”. My “w” was a “v” sound and my “t”‘ became a “d” so I said “vader”.

Interviewer: Uh huh.

Schwartz: And Miss Scott actually showed me how to sound out a “w”. And she showed me how to sound out a “t” and she showed me how to sound out a “th”. I’ll never forget, she’d take tongue between your teeth and pull it in real fast and from a “t” you would get a “th” or from a “d” you’ll get a “t”. And I learned the pronunciation of key words and I have this to thank Miss Scott to teach me how to pronounce and I apparently had a good ear for sound and it developed a good pronunciation of the English language without an accent. One more thing, when I was in the fifth grade, I was discovered before that by Cantor Schnerling who was Cantor of the old Beth Jacob Synagogue and I sang in the choir. I had a soprano, good soprano. I could sing pretty high. My soprano was higher than any girl could sing. And I was in the fifth grade music class and Miss Hillison, who later I found out she was the only Jewish teacher there and I had never knew that. It didn’t make any difference but Miss Hillison was in back of me in the fifth grade class during music and she heard me sing and she apparently must have reported it to Miss Scott that I had a good voice and during that Christmas, that first Christmas when they brought all the classes down into the hall, downstairs in the old Fulton Street School, had a big Christmas tree in Fulton Street School. I guess they’re not used to this kind of stuff now in public schools. And all the Christmas trees were decorated. They gave me a chair. The entire school of kids were all in, all the school kids were in the hall and I got up on a chair and I sang “Silent Night”. It didn’t hurt me. I wasn’t converted and I didn’t know the meaning of the words anyway and I performed . . . . (Tape ends. Section of new tape is not loud enough to hear the words clearly.) . . . . and he contacted Mr. . . . . customers . . . . and there was a little bit of a social scandal in the inner circles of the people and of the group who used to take these annual boat trips and as a matter of fact, the man from Dayton apologized to me because he used to buy hides from my father. And when he came over he wanted to buy my hides and we made peace and I began to sell him some hides because he was a much larger dealer than I was. And I gradually built up the hide business and later on my father passed away and I became a hide dealer, a pretty well-established hide dealer, by myself. And my Uncle Joe had already retired. I owned my Uncle Joe’s property. My Uncle Joe wound up buying the Krakowitz property located over there in the scrap yard and E. J. Krakowitz’ property, all of it in that area became Uncle Joe’s.

Interviewer: Was that about where Handler was?