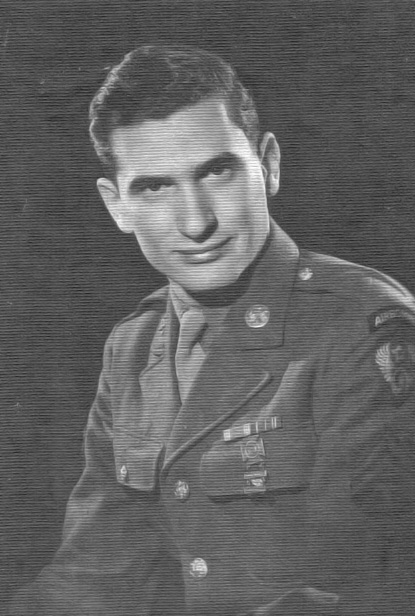

Mike Segal (2014)

INTERVIEW WITH MIKE SEGAL

Interviewer: This interview for the Columbus Jewish Historical Society is being recorded on October 27, 2014 at 2:26p.m. on a beautiful Autumn day. This is Dick Golden representing the Historical Society of the State of Ohio and also the Columbus Jewish Historical Society’s Oral History Project. I’m in the home of Mr. Mike Segal. Mike and Sue Segal are residents of Columbus, Ohio. Mike is a highly decorated veteran of the United States Army. He has an amazing story to tell. We are going to start with Mike explaining why this is all came about. Believe it or not it started in New Zealand about twelve or thirteen years ago. We’re going to mention the name. He and Sue, his wife, were in New Zealand at Christ Church, New Zealand, in the southern end. They were visiting a museum. I’m going to turn over to Mike now and he’s going to tell you the experience that he had, a “bashert” incident, had to happen incident, an unbelievable incident. We’ll go on from there.

Segal: How are you doing Good to see you. I’m ? about this incident in New Zealand. My wife and I were on an Australia/New Zealand tour. It was going to last about a month, I think it was and we were in Christ Church and it was what they call a half day free. That meant that there was no official tour that morning so we were going to be on our own doing whatever we felt like doing.

Interviewer: You were in this museum twelve years ago in Christ Church, New Zealand and you were on your own. You go on from there.

Segal: The museum was basically an arts museum dealing with hand-made art work and it was especially wooden art work. It was our choice. We saw about it in the newspaper and figured that’s a good way to spend the morning. We were up early, had breakfast, went to the museum and checked in. The art work is absolutely magnificent and beautiful. After some looks at art work I got into my more loosened-up territory and I began to do some critiquing of the art work. It was not so gentlemanly but I was critiquing some of it. It was sort of exasperating and this one magnificent huge bowl, it must of been out of a cross family. I don’t know how ancient a tree it was but they made this bowl out of the whole cross-cut of a tree. They just sliced it and used the natural grain of the wood to make it into an art piece, and it was. It was beautiful. Being an art piece cut out of a tree there of course were knot holes from branches, stuff like that. Every time there was a knot hole. somehow or other, in doing the art work and finishing of the wood, they punched some of the knot holes and actually there were actually three, if I remember correctly, three knot holes in this big thing. I was talking and, knocking the art work which I always do and said “My god, who could ever use that bowl, it leaks?” It really leaked. There was no doubt about it, it surely wouldn’t have held water or liquid of any kind..

Interviewer: Okay so this is the start of the conversation. There was this huge bowl with the holes in it.

Segal: Correct.

Interviewer: This is in Christ Church, New Zealand, in a museum. Okay what happened after that?

Mike: I was making all these smart -aleck remarks and there was a couple near by. I had no idea who they were and could care less. They were listening to me preach about this bowl. They got to laughing and making remarks about my remarks.

Before you know it we got into a conversation with them. The couple were about my age, who knows. They seemed pretty warm and personable. When I got through raving about this bowl, they said something about what are you doing here and so forth. We told them we were on a tour and we had a free half a day and we were just on our own time. They said, “Look, we’re natives here, why don’t you let us take you some places that I’m sure won’t be important enough to be included in your tour.”

Interviewer: Okay, so they said they were natives there at that time. They were living in New Zealand, this couple that you bumped into.

Segal: They were from Christ Church.

Interviewer: Okay hang on now, this is going to get more interesting.

Segal: They said, “Let’s get come lunch somewhere, if you like, then we’ll take you on our home-made tour of places that won’t be on your tour. They’re not important enough to be on a national tour but we think you’ll enjoy these things that we can show you.”

Interviewer: Did you get their names, Mike, this couple?

Segal: Oh yeah. They introduced themselves. We gave them our names and we told them where we were from, Columbus, Ohio, in the states. They were thrilled to meet somebody from there. So we ended up with them. So we paired up with them, went to a little restaurant and had some light lunch and they took us to four or five places that were of interest to us

Interviewer: According to what you told me previously, this couple were Eunice and Bert Kopbes and they were living in Christ Church, New Zealand at this time.

Segal: Right. She was a native of Christ Church and they married. They were delightful

people, really nice people.

Interviewer: Now you’re going to hear how this story gets even more interesting.

Segal: While we’re eating lunch and so forth, we’re talking and he says, “I’m not from here, my wife is. She’s born and raised here. I’m an immigrant from The Netherlands.”

I said, “Where in the Netherlands because I fought in The Netherlands during World War II ” He said, ” Do you happen to know of a small town, it’s called Nijnmegen.” I said, “”You mean “Nijmegen.” He says yeah, “How’d you know it had a j in it?” I said, “Because it’s one place I fought. and it was part of Market Garden.”. “Oh, I lived ? in that area, up the side of a heavy duty mountain. and it was right near the battle” I said,

“What do you mean, right near the battle?” He described the battle, actually the ground that I walked on and fought on.

Interviewer: Okay, the man that you met in the museum is telling you that he lived in NJijmegan. How old was he at that time when you were in that war zone?

Segal: He said he was twelve years old and that he lived on a big farm. He said, “When that battle started, I was far enough away from the battle that I wasn’t going to get hurt but I had my father’s binoculars and I found a good, safe place where I could be and I watched the whole battle. That battle was beyond anything I could have imagined with the artillery and the bombs and ?”

Interviewer: Okay Mike, now we’ve got you in that battle scene. Tell us a little bit about how you got into that zone.

Segal: I was a Radar Pathfinder for the 101st Airborne Division. A Radar Pathfinder is a unique experience. A Pathfinder has to know how to maintain and operate the radar which is critical to airborne fighting. Every DC3 that’s involved in hauling out paratroopers and fighters in the battle zone . The whole idea is not to fly over in airplanes and push them out the door. The idea is to drop them in an organized pattern so that Company A is next to Company B and Company B is next to Company C, and so forth in an organized fashion predetermined by the planners of the invasion that’ was coming up, the battle that’s coming up. This was to supplement everything that was happening in Market Garden which was to about face the Siegfried Line so that we could go North of the Siegfried Line. and into Germany which is just backwards from that way the Germans went from Germany into France. We were going to follow their trail basically. We were going to go from West to East. They went from East to West.

The whole idea would be to scatter by radar units and radar control operations through these units all the airplanes that were going to drop the parachutists and get them on the ground so that they knew who was on the flank and who was in front of and who was behind them so that they wouldn’t be poppin off at the wrong people and attacking the wrong areas. This was a safety deal and to make an invasion quicker, faster and more accurate and keep our forces in communication. That’s how it would carry out. That’s what we were doing.

Interviewer: Okay Mike, we got you now in that area. What kind of a plane were you in when you took off from your base?

Segal: Well, we were basically airborne, but not in parachutes because we had too much radar equipment and related equipment that we had to be to get on the ground early. We went in several hours before the parachutists were going to come in. We had to get the radar units on the ground but we got them to right places they were supposed to be. We were at least six to eight hours ahead of the parachutists.

We went down in the glider with eight men. There was a glider pilot, a radar tech which was me, and then eight infantry men who gave us fire power. Once you turn the radar on, following the ground, the Germans knew exactly where you were.

Interviewer: Okay Mike, we got you on the ground.

Segal: The main thing is to get on the ground and turn the ground unit which was there to respond to the unit that’s on the DC3 or the C47s, whichever you want to call them. It’s the same plane. That would be on the lead plane that controls the airborne troops, the jumpers. That’s the whole idea, getting them on the ground in an organized fashion.

So we had to turn it on. If you don’t turn it on, you’re losing the effect of your radar.

Interviewer: So you have to turn these radar units on into a powerful unit.

Segal: Right. So it responds to — the beep goes out from the plane. It’s the responding unit on the ground which sends back the signals that tell the pilot in the plane with the paratroopers we’ve got to go three degrees more to the left, or five degrees more to the right and they could just go right in on it, as accurate as you possibly can. They’ve each got a radar unit for their screen, a TV screen, and it gets the reading just the way they invented that PC, that unit. That’s why it was so valuable.

Interviewer: This is 1944, September, so you can imagine how it is now. It’s much more accurate.

Segal: I’m sure they got some a lot better than what we used back in those days because they don’t get worse. They get better. They get sharper and even more accurate. If they use those things — They don’t use gliders anymore. They use helicopters. They come in with a lot more fire power. That’s the whole idea. Put them on the ground in better condition to fight. I’m sure the equipment that they have today has got to be a hundred times better than the stuff that we used in the infancy of World War II.

Interviewer: We got you on the ground now and you’re setting up your units, the guys in the planes with the paratroopers to jump, in a zone that’s within reasonable proximity of where they are actually needed. They’re getting pretty close. These guys, did they jump where you wanted them to?

Segal: Well, if the radar units are working properly, this is the problem of the radar men that repair and maintain the units. If everything is working right, everything is as accurate as you could possibly get. The men know how to respond. The only problem is that these are technically are very fragile units. It takes a very good radar technician to make sure you’ve got everything right in the unit, high-tuned to do what it’s supposed to do.

Interviewer: Were you able to get most of your guys in in the right area?

Segal: We had a pretty doggone good percentage. If we did get men out of position, they had enough brains, the American soldier, to get themselves into a position that would be fairly equivalent to what the need was.

Interviewer: Okay, so here we are, we’ve got you now, in your group, attached to the 101st Airborne. Is that correct?

Segal: Yeah.

Interviewer: The Airborne guys have jumped and the battle is going on.

Segal: Right.

Interviewer: The British hadn’t arrived yet. You only had a few hours or a day or so to hold that area before they got there.

Segal: Well, number one, the British, as always, were always late. You could never count on them being there when they were supposed to get there. Number one, they were supposed to be there, ready to come in on target but the British were always late.

Interviewer: This is a British division that was supposed to come in or at least a division.

Segal: Well, the British landed at the Juno Beaches. They were supposed to be there in three days and two weeks later they were still not at Achim so that’s when the Germans reinforced the troops that were in Achim which made it tougher for our guys on the ground to take that ground ahead of the British troops. We were in coordination with the British troops.

Interviewer: Okay, so the D-Day operation was June 6, 1944 and here you are now in mid September, 1944 at the Nijmegen Bridge with your radar unit and the 101st Airborne Unit attached to you in a reasonable facsimile of the area and you’re waiting for heavier stuff which would be the British to come in. You were in a holding line now. You were not able to attack because you didn’t have enough people. So the holding line was waiting for the British. Is that correct?

Segal: Well, we were losing time. When you set up and coordinated with all these divisions, multiple languages. There were Polish troops part of that. The 101st Airborne was there. The 82nd Airborne was there. They had some very important ground, as did the 101st. Once you get somebody not being where they’re supposed to be when they’re supposed to be there you can’t (?).

Interviewer: This was the operation Market Garden. It was successful if it would work. Now the British 30th Core. That was the group you were waiting for. They could roll in with maximum speed but they didn’t show up. Is that what I’m hearing?

Segal: Well, they were late. They were so far behind schedule the Germans had time to reinforce all their positions in defense.

Interviewer: Okay ? that’s American Battle History. The British core had to reach Arnhem in 48 hours because the airborne troops, may have been in other areas, could not be expected to hold out longer than without standard artillery tanks and effective supplies and heavy equipment. So here the American guys are there. It’s a thin line. They’re holding it and they’re waiting for the British artillery core to roll in.

Segal: That’s about it. They were late and we were stuck in the mud and the tanks right behind the British were held up because they weren’t moving in front of us.

Interviewer: So then you guys were kind of trapped in because the British didn’t get there. So what happened during this battle. Can you fill me in on this battle?

Segal: The battle includes trying to get across the bridge at Nijmegen to get to the bridge at Achim which was the key b ridge because that’s where they turned East

instead of going North. If you can’t get to Achim, you can’t turn East because you’re

out of position. You’re not where you’re supposed to be. The British being late,

General Montgomery, if you want to call him a general, he was always late. We got tired and we began to call them tea sippers because that’s what most of them were doing. They were screwing off. You can’t win battles when you’re goofing off.

Interviewer: This sounds like a miracle that you got out of there. Tell me how you were able to get out of that mess.

Segal: Well not until we had to give up the bridge at Nijmegen and we had to hold the bridge at Nijmegen until the British had the magnificent retreat. I don’t know what’s magnificent about a retreat except you got your tail whipped.

Interviewer: Back to Eunice and Bert Kopbes. Now Bert Kopbes mentioned that he saw this battle ensuing all from his farm with his father’s binoculars. This is the fellow you met in New Zealand and he’s seeing it as a child, from his farm area, up on a hill. You’re in the thick of it. You had hell to pay to get out of there. What happened, how did you get out of it?

Segal: Well, number one, we had to give up our positions and retreat to get up over the bridge before they blew it up. We had no advice about whether they intended to blow it up or they weren’t going to blow it up. We couldn’t blow it up without our men on the wrong side of the river so we had to sort of guess about the time element, how long we could hold our positions but make sure the British were across the bridge, so we just had to guess. Everything was very close together with our troops. I had about twenty-five men with me. They were good men from the 101st and a lot of strays that we picked up and, by golly, we held our positions. I said to the men, I could just holler to them and I didn’t have to worry. I didn’t need a messenger. I said I will blow a whistle when I think the time is right. I pointed to a man and said you take radar unit number one and you take radar unit number two and when I blow that whistle you run like hell to get across that bridge. You could see that bridge from here.

Interviewer: You’re going back now to get to a safer zone, is that correct?

Segal: We’re trying to get across the bridge to retreat over.

Interviewer: Now the kid, the people that we also have you, a while back, villagers in the city, the town itself, welcomed the Americans for a day maybe or half a day. They thought they were doing to be okay there and along comes these divisions of German, heavy

German, well-equipped German people, in uniform, shooting like hell to kill anybody in sight.

Segal: Right, they were trying to get to that bridge before we could blow it up. As it turned out, we didn’t blow the bridge up. When I blew the whistle and our men started running, I stayed behind with a BAR, a Browning automatic rifle, and as much ammunition as the man with was supposed to have with a BAR. I gave him my rifle and took the BAR because I wanted fire power, but I wanted fire power single shot, I didn’t want it fired on automatic because you blow up too much ammunition just in sporadic fire. You can’t afford that ammo loss.

Dick: So you wanted to get back to the American lines. Initially you wanted to save the British, I mean that our American units wanted to save the British, but since the Germans were able to counterattack, then you had to blow that bridge. Is that what I’m hearing?

Segal: That’s what we thought was going to happen. Ended up they didn’t blow it anyhow because they figured we were going to take it back eventually. We wanted it eventually because we wanted to complete that circuit. We were willing to gamble that we could take it back because we had a bunch of fighter bombers.

Interviewer: You’re on the move now. You’re not running backwards, you’re fighting backwards. You’re saving your lives and the lives of others.

Segal: We were on retreat. I’m the one that’s left behind because I volunteered to stay behind with the BAR and I found myself a nice big fox hole deep enough to keep my head below the horizon. I just sat there with that BAR on single shot and I just would pick them off as they came down the hills. It was beautiful because these were SS troops, the best the Germans had. I loved to go after those black uniforms because they were the so and so’s that ran the concentration camps. Being Jewish, I was glad and very happy to pick them off like a bunch of pigs, which they were. I just laid in that hole as long as I possibly could and when they got too close, I finally ditched the place and brought my BAR and slung it across my shoulders, then ran like a scared crow. I got out of there heading directly for the bridge where my men were heading ahead of me. They were all clear to run and so they got across the bridge and so did I, with a sigh of relief.

Interviewer: Now Mike, I don’t want to embarrass you here but hear that, through this action, you were awarded the Silver Star. Is this correct, as part of this action?

Segal: I was awarded the Silver Star for covering that retreat and volunteering to do it and surviving it. But when the time came for the Silver Star, I didn’t want to take it. I wanted to give it back because when we get beat, we’re not supposed to get awards

and ribbons and promotions and all that kind of stuff. I feel like I covered a retreat and that’s the thing you don’t want to be caught doing. I turned it down originally, but the men who, there were twenty-five men who got out of there ahead of me, said, “No, no, no, you earned it. You should take it.” I took it because of them.

Interviewer: That’s an interesting part. You’ve got it and I’ve seen those medals and they’re on your uniform. You’ve got a couple of them.

Segal: Yes, I got one there and I got one at Bastogne because of another battle I was in. When I won, a little bit unusual.

Interviewer: Well, we’ve had a wonderful afternoon here, hearing about your experiences as a twenty year old GI, actually in the Signal Core attached to the 101st Airborne and dealing with the 82nd guys as well. This is covering the battle of Nijmegen. This is Market Garden battle and it’s in the history books. The British Third Core were a little late in getting there. You covered a retreat with your twenty-five or thirty guys. You schlepped that BAR. I schlepped a BAR in training and they’re not light weight. Let me tell you something, I think they weigh about twenty pounds, close to it. You’re supposed to have two men and sometimes three men on that thing, with a tripod.

Segal: Yes, it’s a tripod. It’s heavy, 17 or 18 pounds.

Interviewer: We’re going to close it up here. I just want to ask you about the Kopbes family that, the other people that you met in Christ Church, New Zealand. I understand that he has passed away. Is that correct?

Segal: Yes, he passed away about a year after our meeting in New Zealand. He was fighting Cancer at that time and his wife hinted that there was no chance for him but he was putting up a battle to get as much time as he could, which I respect. He was just a nice guy, a real guy, and they were even talking about coming to the states. They had our phone number and our address. We said, “Come to our area. We”ll show you as much of the United States as we can. We’d be delighted to have you as our guest. You stay with us as long as you want to be there.”

Interviewer: This is amazing, it’s more than a coincidence, meeting someone halfway around the world, this Mr. Kopbes and his wife. Here you and Sue are in Christ Church, New Zealand and out of a clear blue sky here are two people who were involved in one of the most major battles of World War II in Europe. This Operation Market Garden is the largest battle ever, to this day, dealing with airborne units. There were two airborne units in there, there were the British in it, there were radar units that Mike was in. This is the largest airborne unit battle ever. I think this is a hunk of history. I’m glad that the Columbus Jewish Historical Society and The Ohio Historical Museum will have a copy of this. We’re looking forward to more talking with Mike and Sue. God Bless America.

Segal: I say that many times. God Bless America and God Bless Harry Truman for dropping the Atomic Bombs because I was scheduled for the first wave to hit Japan after World War II ended in Europe. I think Mr. Truman, God bless him, saved my life and about a million other American young men.

***

Transcribed by Rose Luttinger